Preface

When I was a young, impressionable college student, I received a scholarship from the Rotary Foundation to travel from Idaho, my home state, to Bordeaux, France, to study for a year. I tasted my first wines there and, understandably, thought all wines were of the same quality as a fine Bordeaux. It was, therefore, a surprise to return to do graduate work in California and realize that, on my student budget, the best wines I could afford were jugs of Gallo Hearty Burgundy and Italian Swiss Colony California Chianti. However there were also many opportunities to drive up to Napa Valley and beyond into Mendocino County and the Russian River region to taste at the new wineries that seemed to open every day. And there were those special occasions that commanded a special wine: celebratory dinners with Puligny Montrachet, Chteau dYquem (yes, it was expensive but still affordable in those days), and toasts at weddings and graduation ceremonies with California sparkling wine or, when it was truly a grand event, a flute of Veuve Cliquot. Like many Americans at the time, I was initially untutored but learning to appreciate and value the wonderful world of wine, and eventually becoming passionate about all things connected with wine.

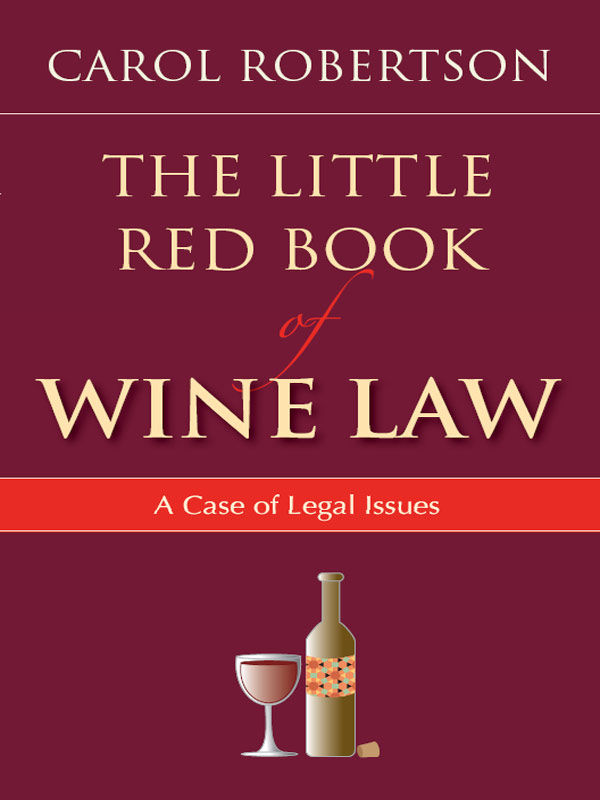

Americans have had a love/hate relationship with wine and other alcoholic beverages from colonial days. This passion is evidenced in the early laws and regulations, and in the cases interpreting the respective rights and responsibilities of those involved in the production and sale of wine in this country over the past century. This book loosely describes some of the milestones in wine history through the perspective of legal cases covering disputes among those involved in the wine industry from its early days at the turn of the nineteenth century through Prohibition and the rebuilding of this country after World War II to the increasing liberalization, deregulation, and globalization of the early twenty-first century.

One hundred years of wine making and sales are told through legal cases dating from 1910 to 2008. These 12 cases cover and interpret diverse subjects such as trademark law, antitrust law, criminal law, constitutional law, and even international treaties, but they all have one subject: wine production and sale. The emphasis of these cases is not entirely on California wineries; one case arises out of Washington state, another out of Illinois, and one each out of Michigan and New York state. However, it is not surprising that California wineries should be parties to more than one dispute, given that California today accounts for a large percentage of the wine production market in the United States, as it has for the past century. This has been a natural result of that states climate and soils, its immigrant population, and also the vagaries of history, as we shall see. It is a fact that California-based wineriesE. & J. Gallo Winery, Kendall-Jackson Winery, and the Bronco Wine Companyhappen to be the largest wine producers in the United States and have the substantial wealth necessary to endure lengthy litigation.

Interspersed through the book are short vignettes, summaries, or descriptions of topics mentioned in the cases, putting greater detail, for example, around trademark law as it pertains to wine, federal wine-labeling law, and state regulation of wine distribution. Some of the vignettes simply describe other legal disputes that provide a counterpoint to the cases, present a comparable dilemma, or simply tell a good wine-law story. And some provide useful information to those who desire a greater understanding of the wine industry and the legal framework for wine regulation.

The extensive migration of European immigrants to the United States in the latter part of the nineteenth century had a profound effect on the history of wine production. Some had been , an estate/family business ownership dispute, involves a family of three Italian immigrant brothers.

One of the most important events in the twentieth century for the alcoholic beverage industry was, of course, Prohibition. ), involve the three-tier regulatory system for wine distribution that was put in place in many states when Prohibition was repealed in 1933, providing a window into the impacts of Prohibition and its permanent effect on the wine industry.

tle with the Charles Krug Winery was perhaps less discussed but was (and remains) longer-lasting and more illustrative of the ebb and flow of organized labors influence. Rising union power in the 1970s led to the passage of the historic Agricultural Labor Relations Act in California in 1978; lessening influence has led to recent cancellations of union contracts in both Napa and Sonoma counties in the 2000s.

As the wine industry has grown in the last 30 years, change has been inevitable. The impact of this change is seen in three very different cases. First, the Napa Valley has become an international destination and is a far different place than it was in 1966, when Robert Mondavi established his historic winery along the St. Helena Highway. The impact of this growth on this bucolic valley is shown in , where the United States was pitted against the European Union over the use of the EUs famous geographic names on wine (and beer) labels and the United States protection of long-time trademarks that may have borrowed those place names.

A glass of champagne, anyone? Or would you prefer sparkling wine?