I n 1985 when I went to work for restaurateur Joseph Baum, first at Aurora Restaurant and later at the Rainbow Room in New York City, he was looking for a classic bar program featuring authentic recipes made with fresh, quality ingredients. The menu I developed at the Rainbow Room Promenade Bar included drinks that had not appeared on a menu since the 1930s, as well as a changing seasonal component. The menu caught the attention of the press and then the public, igniting a spark around the city and eventually around the country. We were on the way to the return of the essential cocktail with real ingredients and classic recipes, but this time there was a twist. Ingredients usually found only in the kitchen began to find their way into the cocktail. First a basil leaf and a strawberry, mashed together with a bit of lemon, honey, and gin. Then more exotic ingredients like hot chiles and yuzu-lemon juice, until at some restaurants it became hard to tell the garde manger station from the bar.

In those years, I used the lore and history of the cocktail to give young bartenders a sense that they were part of a real profession, a profession that had a history. The cocktail is one of the first truly American culinary arts and I wanted these guys to take pride in that heritage. The stories of classics, like the Manhattan and the Collins, the daiquiri and the Jack Rose, gave these guys a way to connect with their customers and infect them with their newfound enthusiasm for the great American cocktail. The stories also provided some small compensation for the rigorous preparation and attention to detail they had not been required to master as mere beverage transporters, a term author Brian Rea once used to describe the post-Prohibition bartender.

The lore and history of the cocktail has been brought into sharp focus by the liquid archaeology of authors like David Wondrich and Eric Felton. Their meticulous research has revealed a culture of the barroom not unlike that of the bars in New York City where I spent years honing my crafta culture that birthed and nurtured the cocktail into the strapping youth it is today. But as cocktails evolve, one essential element remains constant: they must taste good. A good bartender has to master the skill of crafting recipes that appeal to a wide audience while also understanding how to adapt each drink to the individual preference of the guest.

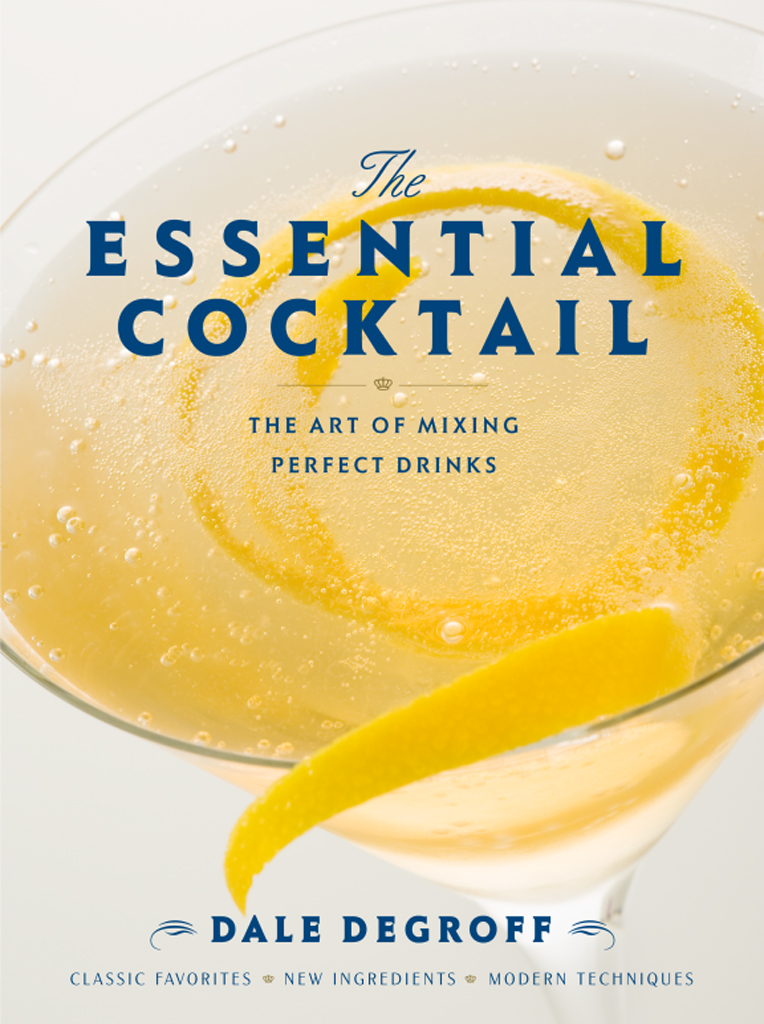

The Essential Cocktail is a cocktail handbook with recipes that work. Having said that, cocktail recipes are often just starting points. In the 1882 Bartenders Guide, Harry Johnson observed that the greatest accomplishment of a bartender lies is his ability to exactly suit his customer. What makes the cocktail unique in the culinary landscape is its relationship with the customer. A cocktail is much more personal than the main course of a restaurant meal. Aside from a few classics chiseled in stone, people want to fiddle; they want to personalize their drink. In all my years working as a waiter (prior to being a bartender), I was never instructed by a customer on how the chef should prepare his hollandaise sauce, but, with very few exceptions, people have a lot to say about the preparation of their Bloody Mary, Manhattan, old-fashioned, and even the ultimate classic cocktail, a dry martini.

I have fine-tuned the recipes to find versions that will appeal to a wide swath of humanitybut not by dumbing them down. In fact a simple short list of ingredients can challenge the skills of the best bartenders even more than a complicated concoction. Simple does not mean easy. And I love that we have come full circle to a time when people can appreciate subtlety and excellence in their cocktails, a fact due in a large part to bartenders returning to the craft of the cocktail.