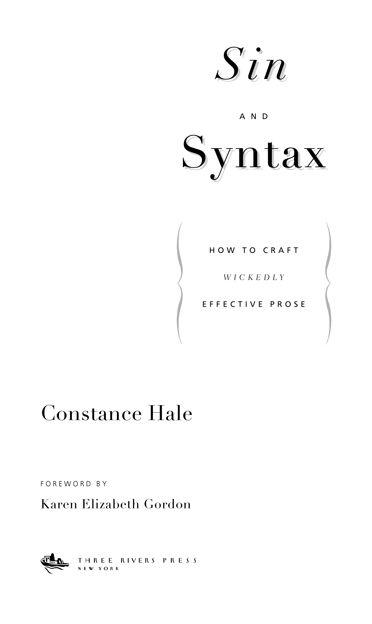

ALSO BY CONSTANCE HALE

WIRED STYLE: PRINCIPLES OF ENGLISH

USAGE IN THE DIGITAL AGE

Copyright 1999 by Constance Hale

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com

Three Rivers Press and the Tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., in 1999. Subsequently published in paperback in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., in 2001.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hale, Constance.

Sin and syntax: how to craft wickedly effective prose / by Constance Hale; with a foreword by Karen Elizabeth Gordon.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. English languageRhetoric. 2. Creative writing. 3. Report writing. I. Title.

PE1408.H299 1999 99-13591

808.042dc21

eISBN: 978-0-7679-0892-4

v3.1_r1

To Madeleine Carter Mayher,

who gave me her love

of the mother tongue.

Acknowledgments

T his book, more than most, reflects the energies not of one author but of many creative misbehavers. My thanks go first to all the writers whose words youll see within these covers.

In casting my net wide for examples of wicked and winning syntax, I was helped by many language scamps, including Martha Baer, Wallace Baine, Frank Clancy, Alex Frankel, Mark Frauenfelder, Jesse Freund, Sam Kane, Tim McGee, Keris Salmon, Brad Wieners, and Gary Wolf. Wallace Baine, especially, came through in spades.

My researcher, Julie Greenberg, proved she could track down anythingeven an almost forgotten 1969 Jell-O commercial. She also sent many useful surprises my way. Meri Brin was unbeatable on the Web and BBS beat. I have half a mind to stand in front of the San Francisco Main Library singing the praises of its reference deskbut the competition for a corner of Civic Center sidewalk is so fierce Ill keep my encomiums here. In particular, I thank Rene Tarshis and Peter Warhit, whose unbridled curiosity and unrelenting helpfulness are shared by their fellow librarians.

Friends and colleagues read parts of the manuscript and saved me from most of my own excesses. Gifted wordsmiths all, Jessie Scanlon, Hollis Heimbouch, Emily McManus, Micki Esken-Meland, and Mary Beth Protomastro were especially generous with the juice. Im not sure which is more dangerousJessie Scanlons withering wit or her purple pen.

Many thanks to my editor at Broadway Books, Suzanne Oaks, who has made me look good, and to Lisa Olney. The book also benefited greatly from the guidance of Matthew Martin and from the attentions of its copy editor, Rosalie Wieder, and its designer, Pei Loi Koay.

I owe a special debt to Karen Elizabeth Gordon. She first sent me spinning in 1984, when I bought her Transitive Vampire; in the past year she became mentor as well as muse, offering me an emergency writing table in the hills, Bariani olive oil, and a couple of killer line edits. Not to mention a foreword!

Also in the special-debt department is my agent, Wendy Lipkind. This book would not have happened without her.

My aunt and godmother, Eleanor Mayher Hackett, started giving me books of poetry before I could talk, and she read my manuscript with the kind of unconditional enthusiasm only an aunt can offer. I am lucky to have her.

And finally, I must thank Bruce Lowell Bigelow, who knows all my sins.

Contents

PART 1

WORDS

PART 2

SENTENCES

PART 3

MUSIC

Foreword

O h, the sentence! The shuddering, sinuous, piquant, incandescent, delicate, delirious, sulking, strident possibilities of it all! A sentence can loll lodalisque, zap, implore, insist, soar, or simply lay out the facts. This handful of words, each with its own humble or brazen function, lies at the heart of every literary genre, every letter, memo, article, thesis, seduction, threat, and retort. In any book you handle, sentences abound. Here, in Sin and Syntax, they strut their stuff in all their guises and moods. From this exploration youll emerge not only a more sharp-witted writer, but also a more attuned reader.

Often when we speak, our ideas fly out half formed, in scattered confessions and pronouncements, in tattered repartee. It is in writing that we have the time and place to shape our sentences and see what we really think, taking ourselves as well as our readers by surprise or storm. We may not know what were going to say (its much more fun when we dont!), and the many ways of combining words help us discover meanings hidden in our own minds. The greater our grasp of these structures, the ampler our repertoire and experience in using them, the farther and deeper we can go.

Books about writing not only aboundthey are shamelessly on the make, taking up precious space in bookstores where literature and lovingly crafted nonfiction should be holding biblioshoppers in thrall. I have read few of these how-to and hold-your-hand-while-you-try manuals because it was literature that taught me how to write, and my cursory glances in this section found few compelling pages on which to alight and linger. But when I heard that my fellow bad girl of grammar and style was writing a book called Sin and Syntax, my nostrils flared, my pulse quickened, my bodice ripped openI had to take a look. My own association with the word syntax postdates my vampirical handbook, and links the divine order of a sentence with scandalous, unfettered behavior. A Yugoslav psychiatrist friend in New York, newly acquainted with my grammatical persona and hearing of my gypsy knockabout life, captured the paradox in a linguistic metaphor: Thats not very syntactical. Thus sin seemed a perfect bedfellow for syntax. Words sleep around, and the tongues of the world are enhanced in the process.

At times Ive envisioned language as a body with its own surge and rhythms and whims, other times as a diaphanous garment that both hides and reveals. But always I see grammar as the choreographer of our language, coordinating the movements of our baffling, flummoxed urge to express, to give voice to the ineffable. Familiarity with the rules of grammar tones our mental musculature, expands our repertoire, sets us free to dance. To break the rules consciously or go around them on purpose is a pleasure multiplied: willful violation, defiance, or deviation with a wicked glint in the eye. The sound, the taste, the thrill of language, its rhythms and edges and riffswhich impart another sort of precisionyou will also find underscored in Sin and Syntax. To me, music is the message, and play, the muse and master of all creation, romps across this realm.

Chapter by chapter, Constance Hales book is about the rigors and romance of sentences, and sharpening ones senses in the reading and the making of them. It shows how a sentence comes together through the dance of words, how one sentence follows another in an effective piece of prose. Here you will see parts of speech in action, make tracks with parallel structure, catch a coquettish phrase at its arc, or curl up with a curvaceous clause. In dens of iniquity you will consort with the demons you once feared; you will dispel misgivings like bubbles of soap. You will return to this very passage and pronounce it overwrought. But flesh and the devil call for flamboyance now and then, and the legitimate haunts of fanfare include prefaces as well as ads. Here you will learn to handle the bones of writing, to articulate a skeleton before its dressed and adorned and sets out to stir up its chosen mischief. A knowing body you will become.