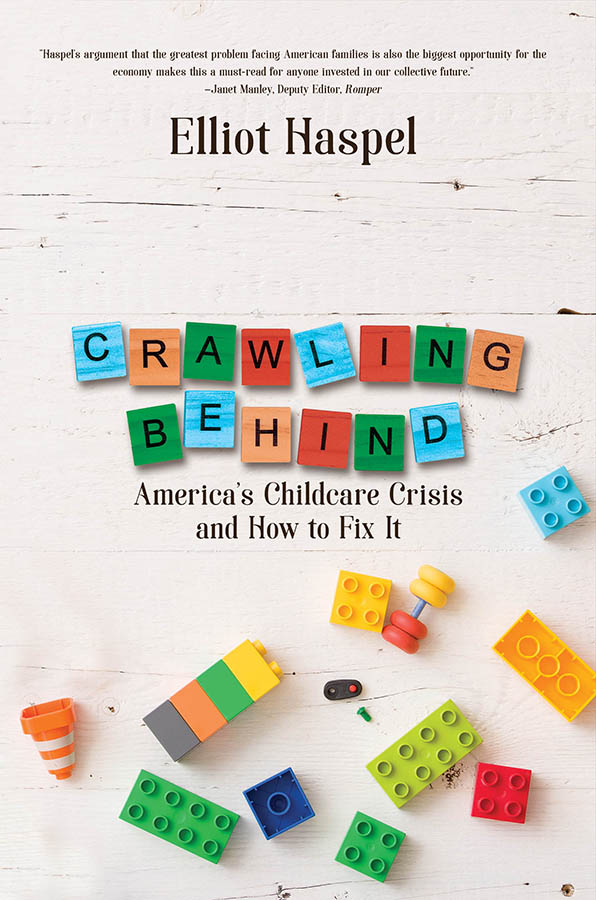

2019 by Elliot Haspel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publishers, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a newspaper, magazine or journal.

The final approval for this literary material is granted by the author.

First digital version

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Print ISBN: 978-1-68433-427-8

PUBLISHED BY BLACK ROSE WRITING

www.blackrosewriting.com

Print edition produced in the United States of America

Thank you so much for checking out one of our Nonfiction titles.

If you enjoy the experience, please check out our recommended title for your next great read !

YouMap! By Kristin Sherry

YOUMAP is a terrific guide to all those who are struggling in their 9-5 life and, beyond that, a terrific guide for anyone interested in getting to know themselves better. IndieReader

To Melissa, my sun; Alma and Esther, our ever-spinning planets.

We live in a world in which we need to share responsibility. It s easy to say, It s not my child, not my community, not my world, not my problem. Then there are those who see the need and respond. I consider those people my heroes.

-Fred Rogers, 1994, as quoted in his obituary

Introduction - The Conversation

As my wife and I prepared for the arrival of our first daughter, we sat down and had The Conversation. Not about baby names or managing in-laws, but the conversation happening over steaming boxes of takeout throughout wide swaths of America: How in the world are we going to pay for childcare?

Childcare is perhaps the most vexing budgetary challenge facing today s young American families. It s causing enormous strain on both parents and kids. It also carries a triple threat to American society writ large. The lack of affordable, accessible, high-quality care is simultaneously an anchor weighing down the mobility of both the middle and lower income classes; an economic dagger that keeps more than a million people especially women out of the workforce; and a plague on the nation s future as untold millions of children miss out on optimal development during the brain s most critical growth period.

By the way, while the early childhood field prefers the more precise terms early care and education or early childhood education, I ve opted for the more commonly used lay term childcare. *I use childcare (sometimes shorthanded to care ) to refer to all caregiving settings, primarily focusing on non-parental care during the first five years of life. This includes what is variously known as preschool or pre-Kindergarten. We ll also talk plenty about stay-at-home parents, and talk briefly about care for school-aged kids. As we ll see, care and education in early childhood are largely synonymous.

Truth be told, childcare costs may eventually pose a fourth, more existential threat to the United States: Birth rates have steadily declined to a 30-year low. In a 2018 survey commissioned by the New York Times , the top reason childbearing-age adults gave for having fewer children than they would otherwise want a reason cited by fully two-thirds of respondents was the cost of care.

The governmental and societal responses to this crisis have been anemic. Weak subsidies for families in poverty don t cover the full cost of care and have absurd, years-long waiting lists. The federal child-related tax credits cap out at a mere fraction of what parents pay. We re fighting a five-alarm fire with the public policy equivalent of beach toy water buckets.

There is a solution. It s relatively simple: start treating childcare like America s universal public education system a common good, easily accessible and free for families.

In an instant, we d be removing a crippling financial boulder from the backs of tens of millions of Americans while supercharging the economy and the brain architecture of the nation s next generation. It would simultaneously be one of the greatest pro-family and anti-poverty tools ever wielded. We d also be injecting enough funding into the system to allow for a functional and high-quality childcare marketplace, including paying critically important teachers a decent wage instead of paying them on par with parking lot attendants.

Unlike the public K-12 system, the needed flexibility of care during the first five years demands a more portable approach. Thus, we should give every family an annual Child Development Credit of $15,000 or so per child , and let them use it on care during the birth-to-five years. We should further provide a Youth Development Credit of $1,000 or so during the five-to-eighteen years to help cover before/after-school and summer care.

We ve shifted our society s idea of what deserves public support many times before. We can do it again, and we can do it now.

* * *

Big societal changes tend to occur in a state of punctuated equilibrium, to borrow a term from evolutionary biology: long periods of little-to-no change followed by spikes of massive change. A good example of this is American enrollment in high schools. From 1910 to 1940, the percentage of American teenagers enrolled in high school leapt from 18 percent to 71 percent. In the entire 19th century, the enrollment percentage had barely budged. This was a tectonic shift in the very structure, rhythm, and expectations of American life, and it happened in a generation.

Similarly, the GI Bill (technically the Servicemembers Readjustment Act ) reshaped American higher education as the country emerged from World War II. That conflagration ended in 1945. By 1947, nearly half of college admissions belonged to veterans. Almost eight million WWII veterans went to college utilizing the GI Bill, in the process spurring the mass normalization of college and the strengthening of public colleges and universities.

Why do these spikes happen? At the simplest level, the pressure becomes too intense to accommodate incrementalism. The rapid industrialization of America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to a clamor from businesses for more educated individuals. The GI Bill, meanwhile, was largely designed out of a cold-sweat terror of what to do with 16 million returning soldiers and wanting to avoid the crises that followed from not having a plan for World War I veterans. In other words, due to a combination of external forces, pressure starts building rapidly, and society can either find a way to vent it or can deal with the consequences of the explosion.

The impacts of these spikes are not just felt on the particular people they re designed to help, such as teenagers or veterans; the impacts are communal. A bumper crop of high school students meant buildings and roads needed to be constructed, teachers and other staff needed to be hired. A flood of new college students meant that there needed to be dorms and instructors to accommodate them enrollment at the University of Miami (FL) more than tripled in two years! and in many cases new institutions of higher education altogether. In 1944 there were 58 community colleges in America three years later, 328.

It s important to remember is that these shifts were expensive, and government at different levels via taxpayers was footing the bill. In the first five years of the GI Bill alone, the federal government shelled out (in today s dollars) over $14 billion in college tuition and living stipends. Localities across the country raised taxes to fund their new high schools since during that era there was weak state and federal K-12 support.

Next page