1. Theodore Roethke, My Papas Waltz, The New Oxford Book of American Verse, chosen and edited by Richard Ellmann, New York, Oxford University Press, 1976.

2. The quotation on is taken from Beyond the Melting Pot, by Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, M.I.T. Press, 1963.

3. Across the Alley from the Alamo was made popular by The Mills Brothers in the 1940s.

My Papas Waltz, copyright 1942 by Hearst Magazines, Inc., from The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Company, Inc., and Faber & Faber, Ltd.

Lyrics from Across the Alley from the Alamo, by Joe Greene. Copyright 1947 by Michael Goldsen, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Michael Goldsen, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-307-81605-4

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78-22346

Copyright 1979 by Vincent Panella and Susan Sichel

All Rights Reserved

v3.1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

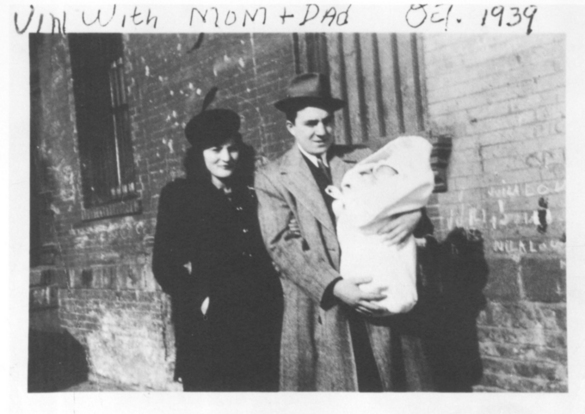

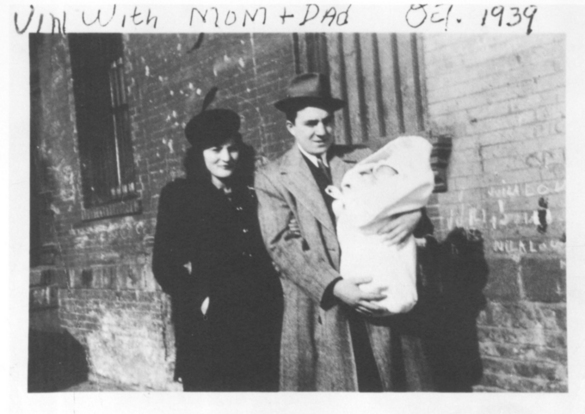

We want to thank all members of the Giaimo and Panella families who so generously gave us both the information and the photographs needed for this book. We also want to thank Marty Kelly for her valued opinions and spirited encouragement, Tracey Penton for his care in designing the book, and Karen Van Westering, our editor, for her support throughout.

For all our families

Contents

Such waltzing was not easy.

Theodore Roethke,

My Papas Waltz

Connections

As a boy I held my ears when my grandmother sang to me in Sicilian dialect. I was relieved that my non-Italian friends seemed indifferent to my grandparents broken English. And although I could ascribe my familys habits and attitudes to being Italian, it would be many years until I understood what this meant. Later in life, when I sought self-understanding, I found in myself the best and worst of my familys values. I felt like Gulliver, waking up with the dawn and seeing the ropes which bound him.

I never knew they were country people. Id never seen their tiny towns in southern Italy, beautiful, poor, serene, but for some, miserable. My family looked upon its origins with mixed emotions: bitterness, nostalgia, and a sense of lost values. Only my Sicilian grandfather seemed resolved about the change in his life. He spoke about his old home without remorse. He had escaped that poverty and isolation. He was having the last laugh.

These attitudes toward Italy were conveyed to my generation implicitly. Only later did I see that America was a choice for the older people, but not an absolute necessity. In Italy they might survive, but they would never prosper. So they came to the tenements with that wave of southern Italian immigrants in the early 1900s, the men unskilled, the women readily employable in the garment industry.

The transition to America consumed their energy. They had little time for the likes of me. I was third generation, ignorant of Italy, and too young to remember the Italian neighborhood we moved away from soon after I was born. I knew my family as city dwellers: my grandfathers railroad workers; my father a city fireman, then bar owner, then real estate broker; my uncles paragons of my city heroes, physically tough men with a disposition to drink and gamble. Men I emulated when I was young, and envious of the tenement life Id never known.

My family was too proud to advertise its struggle in America, and neither equipped nor inclined to articulate an identity to its children. We were Italian and different. Our special gifts and vulnerabilities, these I would discover on my own. I was to learn that my father was Neapolitan and my mother Sicilian, but I had no notion of these concepts as geographical and cultural. I sensed the discord between these two groupsit was more manifest in the womenbut didnt realize until later that its roots reached back to Italian history. At our home in Queens my mothers family lived on the second floor, and we lived on the first. I was more of a companion to my mothers brothers than to my father: he always worked at two jobs. He came home late in the evening, and left early in the morning. Everyone was on the move. My grandfathers worked on the railroad together, my Sicilian grandmother constantly cooked and arbitrated, my father came and went as he pleased, my younger uncles were unruly.

Home was the place for meals and arguments. The meals were memorable, the arguments almost always over money. It was the hurdle they never cleared. At the table my father asked the price of everything we ate. He could always get it more cheaply, downtown. Seeking his approval, my mother would present him with her purchases of food or clothing: he rarely extended praise. I learned his system of control very quickly: he never committed himself to a schedule the family could rely upon. And he always said we could do better. This kept us, using his expression, on our toes.

We were a physical family. There was a good deal of kissing, hugging, slapping, ear twisting, and worse punishments for worse offenses. Disobedience was not tolerated. My father was the supreme authority, my mother a much weaker second-in-command. Neither was a companion with whom intimate fears or feelings could be shared. On those occasions when my father tried to engage me on such delicate subjects as sex and fighting, the circuits slowly shorted. He could not be an autocrat and an equal. My closest companion as a boy was my mothers youngest brother, Mario, an uncle who filled in for my often absent father, and who, without responsibility for my discipline, could be liberal with me. Mario introduced me to the world I wanted to know aboutthe world outside the house.

In time we became less Italian. The move from Hells Kitchen to a non-Italian neighborhood in Queens was the major departure from the familys first culture. And our connection to Italy and family members there, once tightened by a chain of letters and packages, became tenuous. The packages slowed, then stopped. The letters became annual events, notes with the same phrases repeated year after year, notes cast aside quickly. We were here; they were there. English words crept into the language spoken at home and a kind of pidgin was used between first and second generations. Their dialect in its purer form was used as a way of concealing information from my generation. America was knocking at the door. The Progresso food salesman no longer came into our home when the supermarkets carried his products. An uncle married Irish; a sister married black; a cousin married Greek. The culture fractured and healed, fractured and healed, but always with the modification of the previous wound.

But I never knew my family completely. Id grown up in a transition period, when we were shedding one culture and taking on another. I sensed that certain qualities were being lost, others retained or modified. I knew that in order to have a sense of my own identity I had to have a sense of theirs. I thought first of all about why my family built a new life in a new place. I learned that southern Italians were historically a class of migrant workers. While this fact made their passage to America explainable, it didnt shrink the dimension of their struggle. They came to America without skills, and without language, with the Latin roots of English buried deep under their dialect. On the Sicilian side, my family was illiterate in Italian. What could have been so miserable as to propel these ostensibly unequipped people so far from homes theyd held for centuries, homes they felt ambivalent about leaving? What had shaped them, who in turn had shaped me?