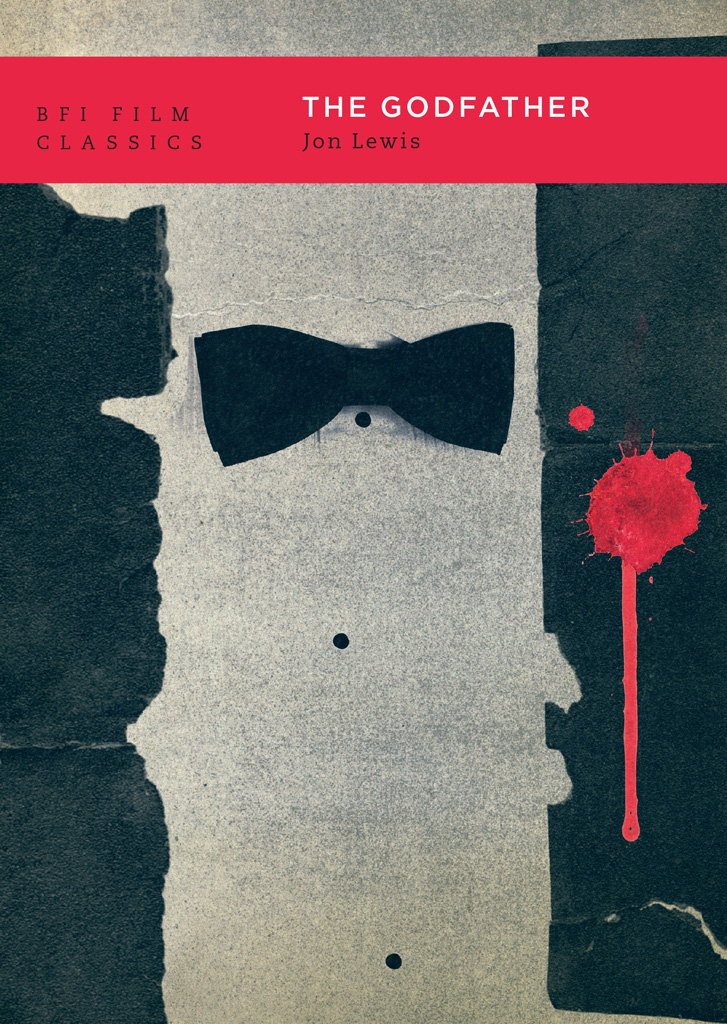

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

For Dana Polan

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in 2010 by Palgrave Macmillan

This edition first published in 2022 by Bloomsbury on behalf of the

British Film Institute

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

www.bfi.org.uk

The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK and the distributor of Lottery funds for film. Our mission is to ensure that film is central to our cultural life, in particular by supporting and nurturing the next generation of filmmakers and audiences. We serve a public role which covers the cultural, creative and economic aspects of film in the UK.

Copyright Jon Lewis 2010, 2022

Jon Lewis has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as author of this work.

Cover artwork: Keenan

Series cover design: Louise Dugdale

Series text design: Ketchup/SE14

Images from The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972), Paramount Pictures Corporation; Little Caesar (Mervyn LeRoy, 1931), First National Pictures; The Public Enemy (William A. Wellman, 1931), Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc.; Scarface (Howard Hawks/Richard Rosson, 1932), Caddo Company; The Big Combo (Joseph H. Lewis, 1955), Security Pictures, Inc./Theodora Productions; Dementia 13 (Francis Ford Coppola, 1963), Filmgroup/Garrick Ltd; Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970), Paramount Pictures Corporation; The Musketeers of Pig Alley (D. W. Griffith, 1912), Biograph Company

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-8390-2458-0

ePDF: 978-1-8390-2460-3

ePUB: 978-1-8390-2459-7

Produced for Bloomsbury Publishing Plc by Sophie Contento

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

The Godfather was a unique product of the Hollywood system, a movie that quite perfectly reconciled the bipolar tendencies of the medium: art and commerce movies and money. Upon its release in the spring of 1972, the film all but invented a new category: the auteur blockbuster. And as such, it set a commercial milestone, singlehandedly pulling a moribund industry (Hollywood unemployment had by then reached 42 per cent, an all-time high) into profitability. The film was as well an indisputable artistic triumph, lauded by filmgoers young and old, by the industry establishment (it received nine Oscar nominations and won three, including Best Picture), and by American movie reviewers, many of whom had by then quite given up on Hollywood.

No movie director in the history of Hollywood has ever had a decade as amazing as Francis Ford Coppolas 1970s, in which the director enjoyed critical and box-office success with The Godfather, The Conversation (1974), The Godfather: Part II (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979), winning for himself five Oscars and the top prize at Cannes, twice. A golden generation of American filmmakers benefited and many of them right away from Coppolas success and his remarkable generosity. Remarkable, as generosity is not so often on offer in the film business; in Hollywood, it is one thing to succeed, another and better thing for those you might be compared to, to fail. If there had been no Francis Ford Coppolas The Godfather, there would have been no Martin Scorsese, no George Lucas, no modern American cinema.

When George Lucas took to the stage at the 1992 Oscar ceremony to accept the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, he thanked his parents, his collaborators and most of all his teachers:

Ive always tried to be aware of what I say in my films because all of us who make motion pictures are teachers, teachers with very loud voices. But we will never match the power of the teacher who is able to whisper in a students ear. Thank you, Francis, for being my mentor.

Though Coppolas career was by then quite clearly on the wane, no last name was necessary because everyone in 1992 Hollywood understood who Lucas was thanking and why.

Five years later, on the occasion of The Godfathers 25th anniversary, the Apocalypse Now scenarist John Milius offered a variation on the theme of Lucass Oscar speech: Francis was the great white knight And when it all gets said and done, he is the best director of our generation. It would be, from almost any angle, foolish to argue otherwise.

The Godfather wasnt ever supposed to be a Francis Ford Coppola film. At least eight other directors were ahead of him in the queue. The studio offered him the job because no one else seemed to want it, because he was Italian (which they hoped would help with the inevitable Italian-American anti-defamation leagues), because they figured theyd be able to push the young director around (a misapprehension of mind-blowing proportion).

A lot has been made of Coppolas love-hate thing with the Paramount executive Robert Evans, whose role in what made it up onto the screen is impossible to discount, even if it will never match what he later claimed it to be. What Evans did well was to surround Coppola with experienced talent. And Coppola took full advantage of these collaborators but that shouldnt ever diminish the scale and scope of his genius in making The Godfather.

One of the key scenes in the film is set in the garden at the Corleone compound as Vito offers some advice to Michael, who has by then taken control of the family business. Robert Towne (a prodigious talent who would a year later write the script for Chinatown, 1974) pulled an all-nighter to craft the scene. Near dawn the following day, Coppola drove him to the set and Brando greeted the by-then exhausted script doctor and asked him to read the scene to him twice. Coppola stayed safely out of the way: he had delegated an important task to a talented writer and saw no reason to complicate matters further. The day before, he had briefed Towne on the family melodrama he was making.