Page List

First published in 2022 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com This e-book first published in 2022 Lindy Wildsmith 2022 All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0 7198 4164 4 Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Photographic credits by Caz Holbrook. Introduction

T oday when we think of preserves, we think mostly about jams, jellies, marmalades, chutneys, cordials, pickles, ketchups and other sugared treats.

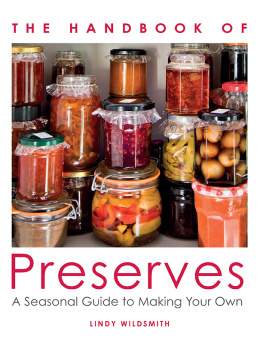

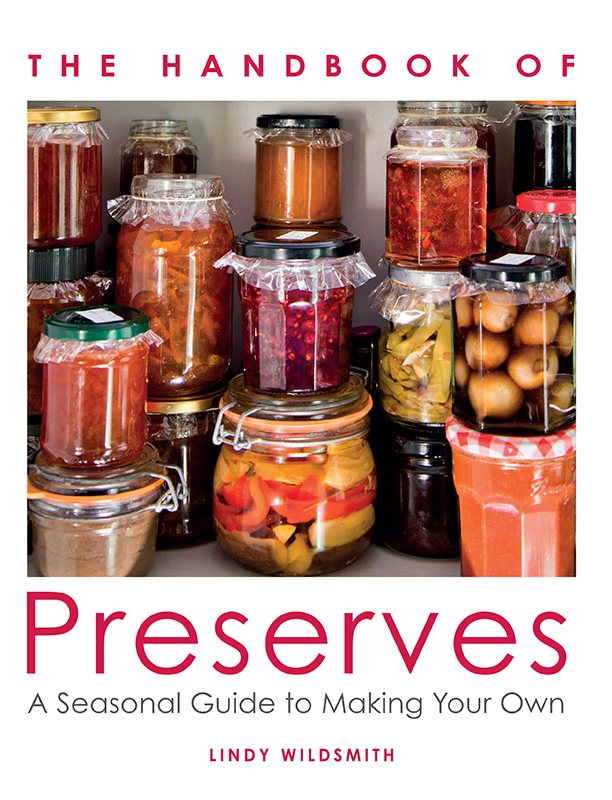

These much-loved comestibles are relative newcomers to the delicious panoply of preserves. It was not until the arrival of cheap sugar from the West Indies in the nineteenth century that they appeared on the family table. Prior to this, sugar was a luxury item, reserved for the highest tables in the land, as prized and as rare as the exotic spices arriving from the East.  Well-stocked shelves featuring jars of jam, jelly, marmalade, chutney, cordial, pickles, ketchup and other treats. As we look back into our distant culinary past, instead of sugar we find salt. For hundreds of years salt was as essential, expensive and just as sought after as crude oil was throughout the twentieth century.

Well-stocked shelves featuring jars of jam, jelly, marmalade, chutney, cordial, pickles, ketchup and other treats. As we look back into our distant culinary past, instead of sugar we find salt. For hundreds of years salt was as essential, expensive and just as sought after as crude oil was throughout the twentieth century.

Salt was as essential to life as breathing. Salting and drying were the only ways of preserving food. Conserved foods were the mainstay of everyones diet from peasants to kings. Salting meat, fowl and fish in times of plenty kept everyone going through the lean winter months. Without salt, whole nations would have starved and voyages of discovery would never have been made: we might even still believe the world was flat and dreams of empire may never have been achieved. When man discovered food lasted longer when hung near a fire, strung in the wind, buried in the sand or laid in the sun to dry, it was no longer necessary to keep moving in search of food and hunter-gatherers began to settle down near lakes or rivers.

They started to make cooking pots of clay in which seawater could also be evaporated to make salt, which was able to draw moisture out of flesh, so drying it and preserving it even longer. These became essential life skills and remained so for thousands of years. With the arrival of fridges, freezers, vacuum packs and ready-made meals in the last century, there was no longer the need to preserve food. Nonetheless we still crave the unique tastes that develop in them as chemical changes occur during processing. The texture, the colour and the taste intensifies, becoming richer and developing into new flavours. Many speculate about the fifth taste, that certain something, that quality of savouriness, which you cannot quite put your finger on, the deliciousness, something that is not sweet, sour, bitter or salty.

The Japanese call it umami and equate it scientifically to monosodium glutamate (MSG), which exists naturally in our food. Parmesan has umami, as do sun-dried tomatoes. A stock known as dashi, made from ingredients including dried tuna flakes or dried mushroom, is the basis of much of Japanese cooking and imparts this special quality to the food. As water evaporates in the preserving process, whether through drying, salting or boiling and sweetening, bacteria is held at bay, prolonging the shelf life, and intensifying and changing the flavours of the foods we eat, making them irresistible, giving them the special taste that we love. We can, of course, simply buy these things: there are more specialists than ever working across the world, using old techniques enhanced by modern technology. There are sheds, workshops and farmhouse kitchens where confits, rillettes and potted titbits are made, as they were hundreds of years ago.

There are cottage industries producing jams, chutney, bottled sauces, cordials and drinks. We have a seemingly endless appetite for good old-fashioned fayre and you will find that the ones we make ourselves are undeniably superior to even the finest artisan product. ONCE MASTERED, THE PRESERVERS SKILL IS INVALUABLE Preserving fruit and vegetables, fish and meat are age-old processes that have at their core something magical: turning base metals into gold, changing water into wine, arresting the march of bacteria. Well, perhaps not as magical as alchemy, but nonetheless extraordinary. Preserving is a skill that can be dabbled in from time to time or reward total involvement. It does not have to involve a great deal of time or expensive and complex equipment.

It is a lot of fun, but you do need patience. Preserving is not an exact science: knowhow plus science over love and patience makes the best preserve. You can give as much of yourself to it as you like, and the more you give the more pleasure you will derive from it. Be warned, however: it is addictive and you will find you want to keep on experimenting. It is a common misapprehension that preserving is a good way of using up inferior ingredients. On the contrary, use only quality produce and preserve it with the best vinegar, oil, fat, wine, herbs, sugar, salt and spice.

You will only get out what you put in. The spices and herbs we use every day, such as cinnamon, cloves, ginger, white mustard seed, aniseed, juniper, garlic and chilli peppers have antiseptic qualities. Some spices such as nutmeg, mace and aniseed also help preserve the flavour of food. Herbs like dill, thyme, bay, parsley, coriander seeds and tarragon help the preserving process. They are not there simply for flavour. There are many methods of keeping foods, but I am going to limit myself here to those that can be made and conserved in a modern domestic kitchen, cupboard or fridge: jam, jelly, marmalade, cordial, curd, chutney, ketchup, pickle, ferment, pot, confit and rillette.

Different methodologies have evolved across the world, depending on climate and available ingredients. Fermentation involves immersion in brine, salt or wild yeasts. Pickling relies on acidic liquids such as vinegar, wine and citrus juice. Potting requires fat, whether butter, lard, duck fat, goose fat or extra-virgin olive oil. Jam, jelly and cordial require sugar. Chutney and sauces require both vinegar and sugar.

I will dedicate a chapter of the book to each methodology and provide a master recipe for each protagonist, which, once learned, will empower the cook to create their own innovative preserves. In the late twentieth century preserving was thought to be old hat, almost consigned to farmers wives, the Womens Institute (WI) and people like me, and was on the brink of disappearing from the domestic kitchen. Today top chefs all over the world use preserving techniques to bring a new edge to the food they produce, creating innovative dishes and menus. Where daring chefs tread, others follow. Uncover the secrets and science of preserving to learn the tricks of the trade and to find joy in simple pastimes that have been enjoyed by home cooks for decades or, in some cases, hundreds of years. Share your preserves as gifts, developing your skills, or take your new-found love to heart and even create a business.

First published in 2022 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR www.crowood.com This e-book first published in 2022 Lindy Wildsmith 2022 All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0 7198 4164 4 Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative Photographic credits by Caz Holbrook. Introduction

First published in 2022 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR www.crowood.com This e-book first published in 2022 Lindy Wildsmith 2022 All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0 7198 4164 4 Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative Photographic credits by Caz Holbrook. Introduction  T oday when we think of preserves, we think mostly about jams, jellies, marmalades, chutneys, cordials, pickles, ketchups and other sugared treats.

T oday when we think of preserves, we think mostly about jams, jellies, marmalades, chutneys, cordials, pickles, ketchups and other sugared treats.  Well-stocked shelves featuring jars of jam, jelly, marmalade, chutney, cordial, pickles, ketchup and other treats. As we look back into our distant culinary past, instead of sugar we find salt. For hundreds of years salt was as essential, expensive and just as sought after as crude oil was throughout the twentieth century.

Well-stocked shelves featuring jars of jam, jelly, marmalade, chutney, cordial, pickles, ketchup and other treats. As we look back into our distant culinary past, instead of sugar we find salt. For hundreds of years salt was as essential, expensive and just as sought after as crude oil was throughout the twentieth century.