Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Scott Stursa

All rights reserved

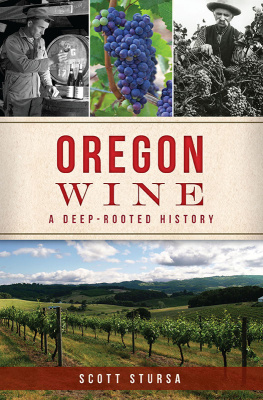

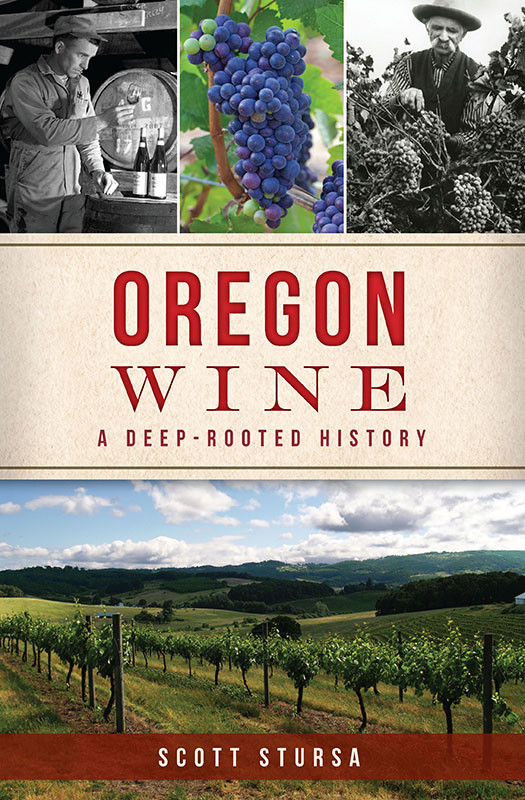

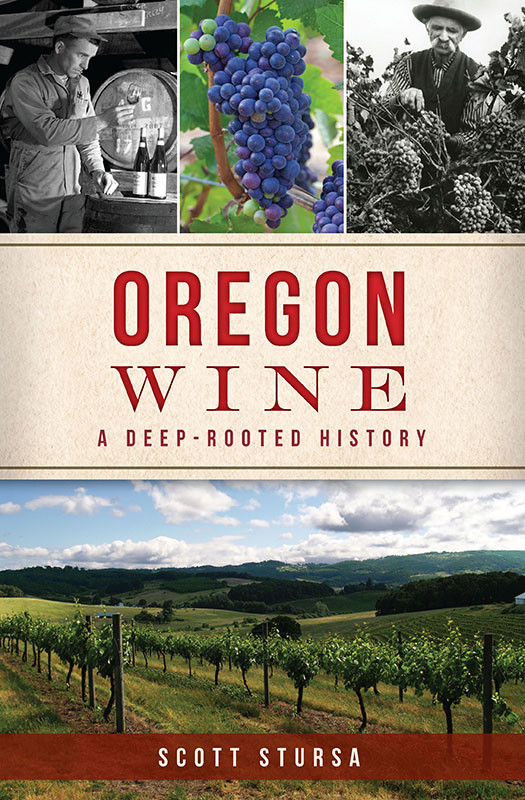

Front cover, top, left to right: Richard Sommer, founder of HillCrest Winery. Courtesy of Douglas County Museum; Pinot noir in a Dundee vineyard. Photo by the author; Unidentified vineyardist in Jackson County, late 1800s. SOHS #12777, courtesy of Southern Oregon Historical Society. Front cover, bottom: Namast Vineyards, located in the hills north of the Van Duzer corridor, gets the full benefit of the cool Pacific wind. Photo by the author.

First published 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.688.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932628

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.053.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

In Memoriam

Jean Jacques Mathiot

18041876

Jack Parker Myers

19242001

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the staff at the Oregon State Archives, the Southern Oregon Historical Society, the Douglas County Museum, the Washington County Museum and the Missouri Historical Society.

Thank you to all the Oregon winemakers and vineyardists, both current and retired, who shared their stories with me. A special thanks to Jason Lett, who was very generous with his time, information and materials.

Thank you to winery owners and managers who shared their time and information, in particular, Mike Kuenz of David Hill and Lonnie Wright of The Pines 1852.

Thank you to Craig Greenleaf for the detailed account of the land-use initiative of the 1970s.

Thank you to the Comini family for the use of the photograph of their ancestor Luigi Comini.

Thank you to Kent Mathiot for the copy of the Mathiot family history and the supplemental information about the family.

Thank you to Brenda Eggert and Helen Gillenwater of the Eggert family for their time, information and materials.

Thank you to Nathan Warren and Amanda Sever of Harris Bridge Vineyard for the marvelous photograph of their vineyard.

Thank you to Rich Schmidt and the staff of Nicholson Library at Linfield College, both for their direct assistance and for their incredible job of creating and enhancing the Oregon Wine History Archive.

And last but not least, thank you to my wife, Kathy, for her patience and forbearance.

INTRODUCTION

THE HOLY GRAIL

My own introduction to fine wine came in 1980, during my late twenties. It came in the form of a mid-range Bordeaux from the 1970 vintage. It wasnt a great wine, but was so much better than anything Id had before. I suddenly found myself with a new interest. My next foray was into California Cabernet, and I liked these as well. The next step was purchasing a couple of books in order to improve my knowledge of wine. One of these listed the four noble varieties, these being Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot noir, Chardonnay and Riesling. I purchased a Pinot, one from a California winery whose Cabernet I liked, but it wasnt very good. I tried several more, with similar results. I tried several Burgundies, all priced in my comfort zone, and didnt like these either. I finally paid the premium for a bottle of 1972 Joseph Drouhin Chambertin-Clos de Bzeagain, not a great wine but so much better than what Id already tried that I was willing to believe that there might be something to Pinot noir after all. I spent the 1980s on a quest to find Pinot both good and affordable. I eventually found a number from California that I liked; these were from cooler areas, such as the Carneros Hills just north of San Francisco Bay.

My experience was hardly unique. There were plenty of wine lovers seeking decent (and affordable) Pinot noir and plenty of California wineries trying to make it. Pinot noir was something of a holy grail for consumers and producers alike, and finding the better ones required persistence (as did making it).

Id heard that there was good Pinot coming out of Oregon, but none of the wine stores in Tallahassee had any. That ended around 1988 or 89, when a newer store (Market Square Liquors and Wines) announced it would start carrying some and was holding a tasting to introduce them. I recall liking most of the wines but dont recall what they all were. The one I do remember was the 1985 Adelsheim, because I took two bottles home with me.

Over the course of the 1990s, I bought progressively more Oregon Pinot, which was not only better than its California competition but usually less expensive as well. I came to appreciate what I think of as the Oregon style of Pinot: lighter, more delicate, with red fruit (raspberry, strawberry) dominating. I still bought the occasional California Pinot; ironically, one of my most memorable wines of the period was actually from California, this being the 1991 Kistler Catherine Cuvee, which was more Oregon in character than California.

My wife and I moved to Oregon at the beginning of 2007, and since then, our only Pinot purchases have been from our new home state.

LIFE IS TOO SHORT TO DRINK BAD WINE

A mantra of mine, I have it on a T-shirt, a ceramic coaster and a refrigerator magnet. There is a variation of it, Life is too short to drink cheap wine, to which I do not subscribe. The correlation between price and quality is well short of 1.0, and with a little effort, one can find good wine that does not bust ones budget, so why bother to drink the bad stuff ? If I find myself in a low-end eatery that has only generic whites and reds, Ill order beer (unless its light beer, in which case Ill drink water). To some degree, this bias affects my beliefs about how much wine was made in Oregon during the early 1800s; the raw material available (wild berries, table grapes and native American grapes) made mediocre wine at best, and I want to believe that most people would have preferred hard apple cider or beer. I must remind myself, however, that vast quantities of bottom shelf wine are sold in this country (by the bottle, bag and box), and it might be that a French Canadian settler of the 1840s was perfectly happy with his blackberry wine. Its something to keep in mind while reading chapter 2.

DECONSTRUCTING MYTH

Anyone whos read books about Oregon wine knows that they usually include a half-to-full-page history of pre-1961 winemaking in the state. These accounts are nearly identical, because for the last forty years, authors have been simply repeating what others have written. As I began to research this book, it became obvious that nearly all of this information is not supported by historical record. Ive identified the most frequently cited non-facts and tagged them as MYTHS OF OREGON WINEMAKING, and these are dealt with over the course of the book.

THE BIRTHPLACE OF OREGON PINOT NOIR

A contentious claim, one which has (Im told) even triggered threats of lawsuits. Its nonsense. Pinot noir has only one birthplace, that being somewhere in what is today the eastern part of France, and it took place two thousand years before Oregon even existed. The phrase is, in fact, a confounding of two entirely different events, the first being Pinots first planting in the state and the second being the genesis of what I call the Oregon Pinot noir phenomenon. The latter is the extraordinary rise of the Pinot-centric Oregon wine industry, a synergy between Willamette grapes that can make a wine rivaling the best of Burgundy and those who understood both how to make that wine and how to create and safeguard an industry. The information presented in this book shows that there is no relationship between the two events, with the first one (who first planted it) being essentially trivia, and the second one (the genesis of the Oregon Pinot noir phenomenon) meriting historical analysis.

Next page