from whence it is hardly possible for persons to return without permission.

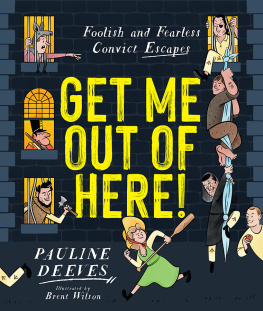

The Ones Who Got Away

Escape attempts began as soon as the convicts of the First Fleet came ashore at Sydney Cove. There were no prison bars to contain the 775 convicts and, needless to say, all the efforts of the guards and marines could not possibly prevent cunning or desperate bids for freedomand there were many.

Probably the first man to escape by sea was French-born convict Peter Parris, sentenced to death for burglary in Exeter in 1783 and transported on the Scarborough.

French explorer La Perouse was camped at Botany Bay for many weeks after the First Fleet arrived at Sydney Cove and, within days of the convicts being set ashore, escapees began visiting his camp, some seeking asylum or places in his crew. La Perouse told Lieutenant William Dawes, who visited him at Botany Bay, that he turned them all away, with scant rations sufficient to get them back to Sydney Cove.

La Perouse was a man of his word, but it does seem odd that the French-born Peter Parris disappeared within days of the colony being established, never to be seen or heard from again. My guess is that he died with the rest of the La Perouse expedition, after the two ships were wrecked on Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz Islands, some 300 miles (480 kilometres) north of Vanuatu. Whether La Perouse knew Parris was taken on board or not, who can say?

In the earliest days of the settlement some of the more naive convicts attempted to flee overland and met their death in the bush from starvation or fatal encounters with various Indigenous tribes, so it would have quickly become known that the only sane and practical way to escape was by sea. Escape of any kind was highly unlikely to succeed, but life could be grim for the convicts, whether they stayed or ran. After all, the whole point of sending convicts to Botany Bay was that the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury knew it was a place from whence it is hardly possible for persons to return without permission.

Hardly possible perhaps, but not entirely impossible.

In September 1790, a former seaman and highwayman, John Tarwood, stole a leaky boat from the South Head lookout station and set off for Tahiti with four other convicts.

Judge Advocate Collins, in his journal for September of that year, noted:

In the night of the 26th a desertion of an extraordinary nature took place. Five male convicts conveyed themselves, in a small boat called a punt, from Rose Hill undiscovered. They there exchanged the punt, which would have been unfit for their purpose, for a boat, though very small and weak, with a mast and sail, with which they got out of the harbour. On sending to Rose Hill, people were found who could give an account of their intentions and proceedings, and who knew that they purposed steering for Otaheite. They had each taken provisions for one week; their cloaths and bedding; three iron pots, and some other utensils of that nature. They all came out in the last fleet, and took this method of speedily accomplishing their sentences of transportation, which were for the term of their natural lives.

The last fleet referred to here is the Second Fleet which arrived in June 1790. The convicts involved had only taken three months to decide they didnt like the prospect of spending life sentences in New South Wales. Tahiti is, however, a long way in a leaky boat and, five years later, in August 1795, the four survivors of this daring escapade were found by Captain Broughton of the Providence, alive but somewhat emaciated at Port Stephens, where they had survived due to the generosity of the Indigenous people.

Collins recorded the event:

Captain Broughton found and received on board four white people, (if four miserable, naked, dirty, and smoke-dried men could be called white,) runaways from this settlement John Tarwood, George Lee, George Connoway, John Watson (Joseph Sutton having died) They told a melancholy tale of their sufferings in the boat; and spoke in high terms of the pacific disposition and gentle manners of the natives Each of them had had names given him, and given with several ceremonies. Wives also were allotted them, and one or two had children They told us a ridiculous story, that the natives appeared to worship them, often assuring them, when they began to understand each other, that they were undoubtedly the ancestors of some of them who had fallen in battle, and had returned from the sea to visit them again.

A few years later, sometime during the first decade of the colony, a group of convicts undertook one of the most bizarre escapes. They stole a boat and escaped from the settlement at Sydney, but headed south. Seven of them were found in 1798, living on an island near Western Port, in what was later named Bass Strait. The man who found them, a very surprised George Bass, was supposedly the first European to explore the area. The men had been abandoned there by the rest of the runaway group. Bass, who was exploring in a whaleboat with six convict rowers, set five of the men ashore with directions to Sydney, a compass and rations, and took the two weakest on board for the return trip to Sydney. Those set ashore were never seen again.

Naturally Bass asked them what were they doing on an island off the south coast of the continent, with no means of leaving. They replied that they had been trying to sail to China but had been abandoned by the rest of the group. Perhaps those who left them on the island perished attempting to find Chinasomewhere in the Great Southern Ocean!

Some 40 years later, in an act of daring piracy, a bunch of desperate convicts stole a shipthe brig Cyprusand sailed to New Zealand, Tonga, Japan and China. They were caught and sent to be tried in London and several were hanged for piracy. There were other daring escape attempts in the meantime.

This is the story of an escape that occurred when the settlement was just three years old, almost exactly six months after John Tarwood and his four companions set out in a leaky boat for Tahiti.

Unlike the spontaneous or opportunistic and doomed attempt by Tarwood and his mates, the escape of William and Mary Bryant, their two children and seven convict companions was carefully planned and well prepared. The Bryants and their crew knew exactly where they were headed. Unlike Tarwood, they also knew how to get there.

Against all odds, in 1791, the convict Mary Bryant not only escaped, but eventually successfully returned to her home in Cornwall; whats more, she received a pardon and financial aid.

Mary Broad

Mary Broad was born in 1765 into a fishing family in the town of Fowey at the mouth of the River Fowey, about 6 miles from St Austell in Cornwall. At nineteen she moved to the much larger town of Plymouth, some 30 miles to the east, seeking work.

There she evidently fell into bad company and criminal activity. In company with Catherine Fryer and Mary Hayden, she robbed and violently assaulted a spinster named Agnes Lakeman on a public street in Plymouth. Mary appeared, listed as Mary Braund, with the other two at the Exeter Assizes in 1786, charged with stealing goods valued at 1 and 11 shillings, including Agness silk bonnet valued at 1 shilling. On 20 May 1786, all three were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. A month later this was commuted to seven years transportation and Mary was taken from Exeter Gaol to the hulk Dunkirk, at Plymouth. There she awaited transportation to the planned Botany Bay convict colony.

Next page