Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Christian Holmes

All rights reserved

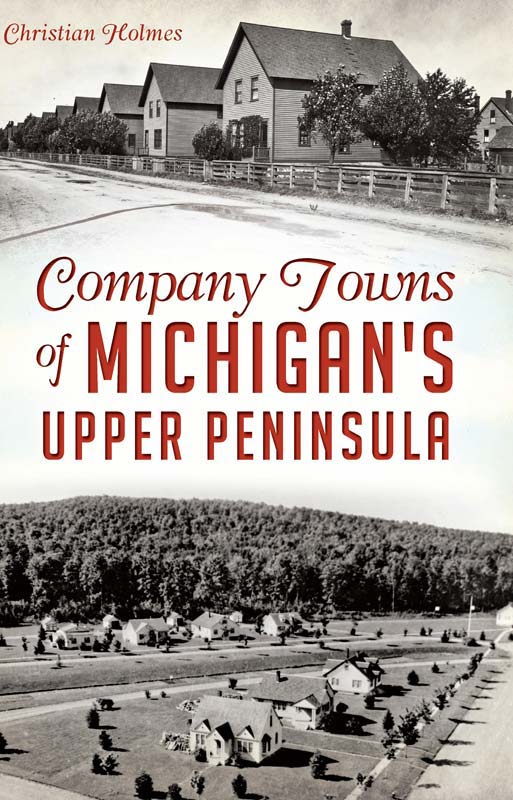

Cover images: Delta County Historical Society, Nahma Township Historical Society and Michigan Technological University Archives.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.276.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015934850

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.742.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to my father, George, who enjoyed reading the four-volume set of

Michigan as a Province, Territory and State over and over.

PREFACE

This storys journey began in September 2011, when I was invited to a planning meeting for an exhibit at the local Bonifas Art Center in Escanaba. I was enlightened to the prior existence of a company town thirty-five miles from where I had lived for forty years. The Selling of Nahma exhibit told the story of the sale of one company town in the Michigan north woods in 1951. My role was to assist in the research, and my investigations led to the discovery of a remarkable number of company towns in Michigans Upper Peninsulas history, beginning in the 1840s, with some existing into the 1990s. The second hook that caught me was that the company town phenomenon received so little mention in the U.P. history literature. Why was this? When The History Press indicated an interest in a telling of the story, I was along for the fascinating ride.

Its impossible to overlook the emotional side of this story. The individuals who lived in these towns experienced remarkable hardships. Working conditions were arduous: logging was done in the winter snow, ice and very low temperatures. The mines were no betterdirty, dangerous work underground by candlelight, with cool stale air and the threat of premature explosion of dynamite or cave-ins. Lumber mill work meant operating mechanical cutting devices before any notion of safety guidelines. Women worked from before sunup to past dusk in cramped conditions. The disparity in wealth with owners could be tolerated only because others lots were no better. One woman who grew up in the Keweenaw Peninsula had four family members who were either killed or disabled in mine accidents. Lofty talk about acknowledging the interests of investors or owners runs thin in this context.

The next awakening I had was in realizing the tremendous debt one has in assembling a story such as this. My confession is that Ive too frequently skipped or skimmed the lists of contributors whom authors thank for making their accomplishments possible. My list is long and begins with the scores of historical society volunteers who collect, organize and assemble historical articles, photographs and ephemera to document the history of their communities. Especially notable were the Nahma Township Historical Museum, the IXL Historical Museum, the Delta County Historical Society Archives, the Ontonagon County Historical Museum, the Newton Township Historical Museum and the Chippewa County Historical Society. Notable individuals who assisted from those organizations were Tee Lynts, Glenn Lamberg, Karen Lindquist, Judy Meintz, Joan Daniels, Bernie Arbic, Lucille Kenyon, Daniel Cvengros and Bruce Johanson. The library staff at Bay de Noc Community College, the Escanaba Public Library, Michigan Technological Universitys Library and Archives, Bayliss Public Library and the J.M Longyear Regional Research Library were also instrumental. Individuals who agreed to be interviewed included Rose Fish, Philip Miller, Albert Winberg and Arne Anderson, among others.

Unique contributions were made by Ann Bissell, Betty Sodders, Sterling McGwinn, CJ Havill, Mary June, William Cummings, Greg Dumais and Ellie ODonnell. I must also salute the authors listed in the concluding bibliography; they were the trailblazers whose detailed documentation and insight made this overview possible and to whom I owe a tremendous debt. Encouragement and support were provided throughout the three and a half years by my son, Adam; my wife, Linda; and my daughter, Alicia. Heartfelt appreciation to you all.

INTRODUCTION

The common knee-jerk response to the subject of company towns is usually negative. We conjure visions of unscrupulous bosses taking unfair advantage of coal miners in West Virginias Appalachian region, where poor souls never escape a vicious cycle of toil and price gouging as they stumble between deplorable working conditions and the mandatory company store. Tennessee Ernie Fords ballad line, I owe my soul to the company store, is etched in the popular subconscious. Historical research presents an opportunity to balance such notions with facts as they emerge.

Much of the Upper Peninsula (U.P.) business history has focused on the industries themselves (e.g., sawmill production and mine equipment) and very little on the lives of those average souls who labored in those firms, let alone the business model of the company town. In fact, one could easily conduct a great deal of reading on U.P. business history without any indication that the company town model or some variant of such was common throughout the region. Certainly between 1850 and 1990, there were more industrial locations that did not contain all the hallmarks of a company town (like industry-owned houses and retail stores) than did, but company ownership has not been adequately discussed as a common theme in U.P. history. Over time, the list of such company-funded services expanded from rental housing and retail sales to include medical services, disability payments, pension benefits, construction of community recreation/entertainment centers and free or minimally priced power, water, sewer or wood fuel. These went beyond the extension of a good corporate citizen, such as donating land or building materials for schools or churches.

My research on company towns in the U.P. led to several discoveries on the topic of company towns in general. They have not been confined to the coal mining district of the United States, as examples can easily be found in New England, the South, the West and the Northwest. They are not just a thing of the past or even confined to the United States. Company towns are alive and well in places like Kohler, Wisconsin, and South America, as well as in some of the technology industries. The term paternalism is commonly applied to the phenomenon of such company ownership, characterized by single-industry towns where the employer owns a substantial number of employee homes, a general store and, frequently, medical services. In the U.P., it was not an all or nothing situation with the services. Some employers provided housing but no retail store. In many communities, employees had the option of owning their homes (usually at a distance from the workplace) on either their own land or property rented from the company. Over time, it was not uncommon for tenants to have the option of purchasing their homes. Likewise, many towns had a company store and also a privately owned one, although it was understood that pricing would be comparable.

Next page