Copyright 2009

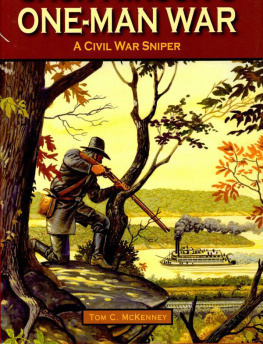

By Tom C. McKenney

All rights reserved

First printing, January 2009

United Kingdom edition, May 2009

Second printing, November 2009

Third printing, October 2010

Fourth printing, April 2012

The word Pelican and the depiction of a pelican are trademarks of Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., and are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

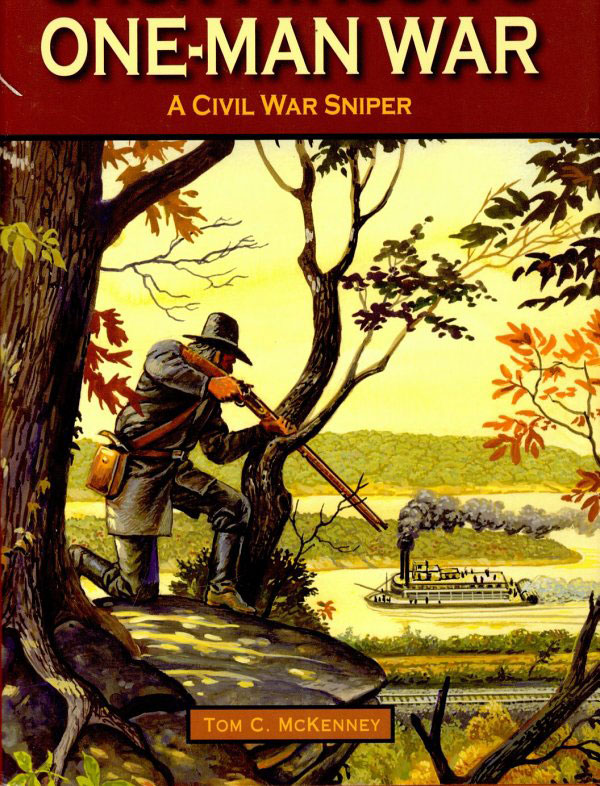

McKenney, Tom C. (Tom Chase)

Jack Hinsons one-man war / Tom C. McKenney.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58980-640-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Hinson, John W., 1807-1874. 2. Hinson, John W., 1807-1874Family. 3. Landowners TennesseeStewart CountyBiography. 4. FarmersTennessee Stewart CountyBiography. 5. Bubbling Springs (Tenn. : Farm)History. 6. Stewart County (Tenn.)Biography. 7. SnipersConfederate States of AmericaBiography. 8. Guerrilla warfareTennesseeHistory19th century. 9. TennesseeHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Underground movements. 10. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865 Underground movements. I. Title.

F443.S7M35 2009

976.83504092dc22

[B]

2008042121

Printed in the United States of America

Published by Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.

1000 Burmaster Street, Gretna, Louisiana 70053

For all those who did the dying, and those who grieved

IN MEMORIAM

Jay Massey, Straight Arrow, of Girdwood, Alaska; outdoorsman; freelance writer; beloved husband and father; and a young man of integrity with a nice heart who, while pursuing this story with me, was taken so suddenly from us by cancer.

Contents

A brother offended is harder to be won than a strong city.

Proverbs 18:19

Preface

Concerning Quotations

Quotation sources throughout the text are as attributed, or explained in the text. Quotations at the beginning of the prologue, each chapter, and the epilogue, not otherwise attributed, are the authors, taken from the text of that portion.

Concerning the Details

This book has been researched, documented, and written as history. It has been an extremely difficult job: first, most of the events occurred more than 140 years ago; and, second, the story has been suppressed, since the war years, by the family. The storys suppression was motivated, in the beginning, by fear of the occupying Union forces retaliation during Reconstruction. Two generations later, the time of Jack Hinsons grandchildren, some family members considered the old mans exploits to be an embarrassment since he had been, in a sense, an outlaw, a wanted man with a price on his head, a notorious killer. In that locally prominent family, he became a topic not to be discussed, and silence settled over Hinsons story.

As a result, important details, that would otherwise flesh out and enrich the account, were forever lost as many of them were literally taken to the grave. Very few of the details survived the death of Jack Hinsons grandson and namesake, John S. Hinson, in 1963.

When I began the research, almost nothing was known beyond those few words on the historical marker where I began (and part of that was in error). Even the exact location of the Hinson plantation, Bubbling Springs, was not known to the family, nor was the location of their postwar home, Magnolia Hill. The family knew the story of the execution of the Hinson sons, but no one knew where it happened or even which two sons were killed. Nothing was known of the arrest at the time of the surrender of Fort Donelson nor the brief imprisonment of the two sons who were later executed. Nothing was known of Jacks activities during and after the battle or his acquaintance with Grant and the Confederate generals. Nothing was known of the sworn affidavit concerning the surrender of Fort Donelson, which he executed a year later. Nothing was known of Jacks taking of the loyalty oath, his citadel on Graffenreid Bluff, or his postwar status and activities. Camp Lowe, the Fort Heiman satellite and base camp for patrols sent out after Jack Hinson, was forgotten, and its location was unknown.

In the beginning of the work, little was known about Jack Hinsons nearest neighbor, not even his identity, whose plantation home was taken over and used as the Union hospital during the battle. Information on his other neighbor, whose home became Grants headquarters for the Fort Donelson battle, was also scarce, except for the two oft-repeated words: Widow Crisp (and, at the time of the battle, she was not yet a widow). The historical marker, supposedly identifying the location of the Crisp home, is almost a half mile from the actual site. A passing comment by an area librarian led to interviews with a rich secondary source, the granddaughter of Mrs. Crisps son. He had told her, many times, what he experienced in February of 1862 during the battle. Only through him, do we now know of the sensitivity, kindness, and compassion shown to Mrs. Crisp and her son by General Grant and his staff. Through him, we now also know Martha Crisps full name, how she became Widow Crisp, about her life and remarriage after the battle, where she is buried, and how wrong Gen. Lew Wallaces white trash characterization was.

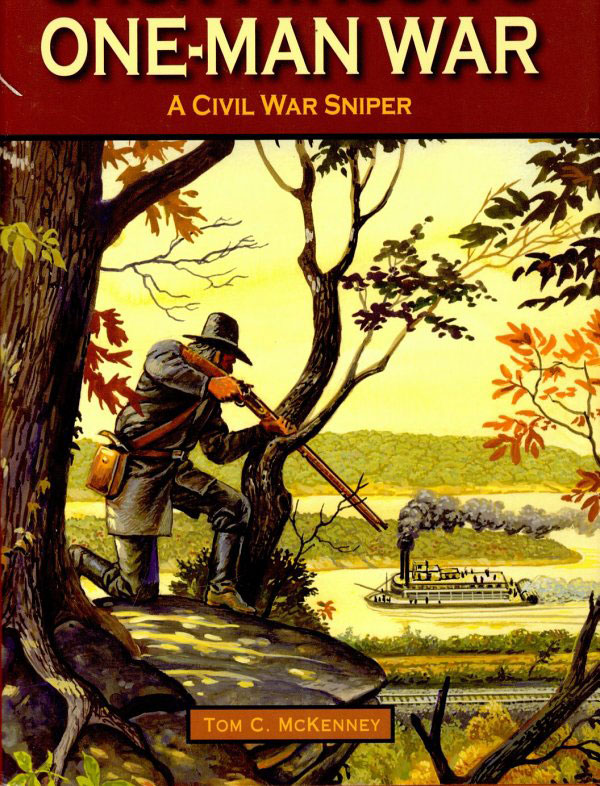

Jacks special rifle was found, traced to its current owner in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and we now know its history and have a chain of possession. A nineteenth century published recollection of Nathan Bedford Forrests adjutant, Maj. Charles W. Anderson, which told of Hinsons guiding Forrest on at least three raids, confirmed Anderson-Black-McFarlin family tradition concerning Jacks relationship with Forrest.

Most of what we now know about Jack Hinson and his family was dug out the hard way: traveling to pursue the slightest leads, asking thousands of questions, placing newspaper ads, and searching archives. When the research began, four of Hinsons great-grandchildren were still living; they provided the few surviving family traditions, letters, photos, etc. still known to exist.

The Hinson family Bible, letters, photographs, and other records that would have answered so many questions were apparently destroyed when Federal troops burned their home at Bubbling Springs. Few records of that kind have survived, mostly those of Jacks children and grandchildren, and they provide little insight into the heart of the storyJacks career as a self-appointed Confederate sniper.

The foundational facts of the events are known and documented, recovered in exhaustive research of the records of the National Archives, the Kentucky and Tennessee State Archives, records at Fort Donelson, collections of libraries and historical societies, nineteenth-century newspaper accounts, written reminiscences of contemporaries, and multisource family traditions. We know, for instance, about the armed Union troop transport that, under Hinsons deadly rifle fire, surrendered to that one old man; most of the details, however, are unknown. The same applies to his relationship with Grant, Pillow, Forrest, and others; the burning of the home; the incident in the Hundred Acre Field; his familys tragic exodus in a blizzard; and his citadel on the ridge above the Towhead Chute. We know that they occurred, but, in the writing, many of the details have had to be assumed. In most cases, only God really knows what was said, what people thought and felt, which way the wind was blowing, what Jack ate in the wilderness, or where the slaves stood as the house burned. In every case, the principle followed in assuming such details was this: they were chosen because, in light of the evidence that does survive, local custom, and the historical context, to choose otherwise would have been illogicalflying in the face of reason.

Next page