SOUTH TO ALASKA

From the Heartland of America

to the Heart of a Dream

by

Nancy Owens Barnes

Published by Rushing River Press

P. O. Box 95

Priest River, ID 83856

Copyright 2010 Nancy Owens Barnes

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without expressed written permission from the publisher.

The print version of this book is distributed by Ingram Book Company and available through bookstores, online booksellers.

Front cover photos:

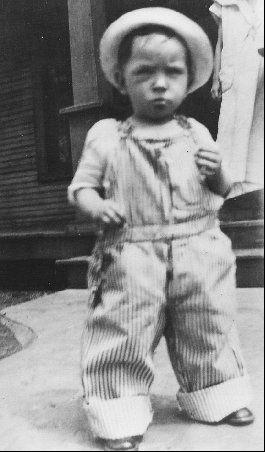

Melvin Owens and dog, Oklahoma, circa 1926.

View from Pennock Island to Ketchikan waterfront. Photo 1995 Jerry Owens.

Interior photos by Don Owens, Jerry Owens, Nancy Owens Barnes and others.

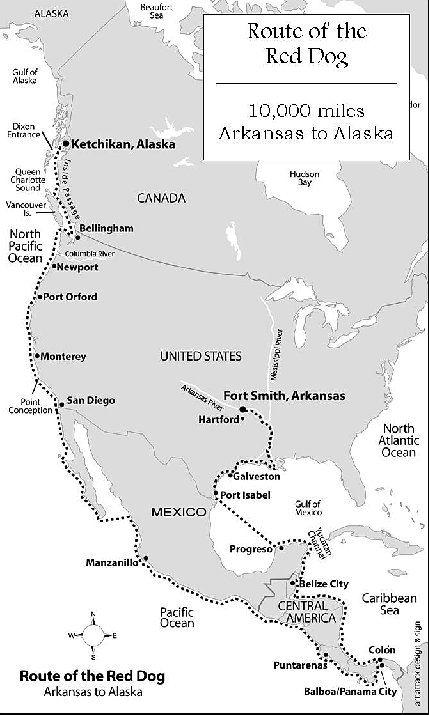

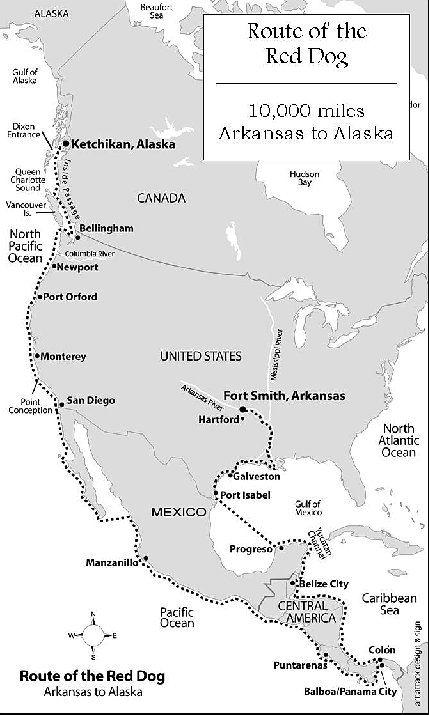

Maps: Art Attack Design and Sign

Dedication

Cecil Marie and Melvin, Alaska, 1961.

To the loving memory of my parents, Melvin George Owens and Cecil Marie Owens, whose contributions and sacrifices for the love of our family will always be treasured. And to my three brothersJerry, Gene and my late brother Donaldwith love and admiration.

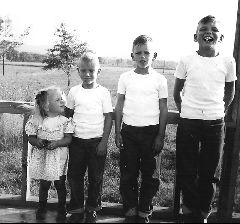

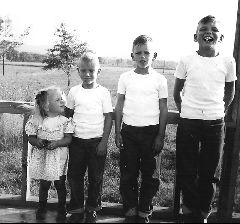

Author and brothers at Perkins farm, Oklahoma, 1951.

Acknowledgments

I especially want to thank

my husband Tom, for his consistent encouragement and faith, and who answered all of my periodic fears and doubts that surfaced while writing this book with, Yes, you can.

my sons Devin and Nicholas, who, when I first began writing this book, waited patiently for overdue dinners and undone laundry. Their drive for excellence makes me proud, and their shining imaginations have often stirred the pot of my preconceived notions.

I also thank

Winona, Kathy, Janet, and all the family and friends who cheered me on and waited so long for the arrival of this story.

Mike Burwell of the University of Alaska at Anchorage, my first official writing instructor who helped light the path to this book.

Rhoda Carroll of Vermont College for her early reassurance.

Elizabeth Lyon of Editing International, for her honest and crucial advice.

Hook your wagon to a star...

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Table of Contents

The following story emerges from first-hand accounts, research, interviews, and entries from the Red Dogs ship log. Some suggested I fictionalize the story. By doing so would allow me to drive drama to a higher level and to void my worries about maintaining truth. But I felt turning the story into fiction would detract from my primary intent: to give my father credit for his achievements, which was never in his nature to claim for himself.

Even though I interviewed my parents extensively, none of us can remember exactly what we or others did or said moment by moment after so many years. But by knowing the circumstances of certain situations, the habits and character nuances of the people involved, and with my parents review of the manuscript, I feel I have presented an accurate rendering of events.

Excerpts from the ships log remain as my father entered them, with only occasional minor revisions for clarity and consistency of format. Because he made the majority of his journey aboard the Red Dog alone, I have drawn from a variety of sources to help illuminate the backdrop of his travels, such as references on sea life, geography of Central America and Mexico, profiles of various ports of call, and seamanship. Two valuable resources included David McCulloughs The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 , and The Oceans: Their physics, chemistry, and General Biology by H. U. Sverdrup, Martin W. Johnson, and Richard H. Fleming.

South to Alaska takes the reader on two journeys. On one, the reader becomes a passenger aboard the Red Dog as it makes its way from Arkansas to Alaska in 1973. On the other, the reader follows a dream that begins in a one-room, Oklahoma schoolhouse in 1926, and ends decades later on an island in southeast Alaska.

To the outside world, some would have considered my father a common rural carpenter. To those of us who knew him, though, he was a gentle geniusnot of mathematics, science, or literature, but of determination, resourcefulness, and independence.

Here is his story. Here is how the manifestation of one boys dream came about.

Arkansas to Alaska

Dawn of a Dream

AT THE SOUTHERNMOST surge of land rising from the vast footprint of the Rocky Mountains, a tall fin of peaks known as the Sangre de Cristo Range straddles the Colorado-New Mexico border. From the chains eastern face the terrain tumbles, dropping and flattening to form a swath of interior plains that tilt and sprawl eastward across Oklahoma. Near the border of eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas, the land again lifts, elevating into the Ozark, Boston, and Ouachita highlands before sloping down into the Mississippi River basin and the Atlantic plain of the Gulf of Mexico.

Snowmelt and rains drain from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, collecting and growing into the Cimarron, North Canadian, and Canadian Rivers, each etching its watery path across the arable and pastoral lands of Oklahoma, then washing into the Arkansas River at the eastern edge of the state.

Melvins story began near the center of Oklahoma where the North Canadian River wigwags through Oklahoma County. Oklahoma County once held a place in the Unassigned Lands, a donut-hole of land surrounded by the Oklahoma Territory when the territory served as a reservoir for relocated American Indian tribes in the 1800s. After President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862, the Unassigned Lands opened to homesteaders in the Land Run of 1889 when, in April of that year, thousands lined its boundaries and, at the boom of a canon, rushed to stake their claims. Some homesteaders encountered Sooners who snuck past U. S. Army cavalry patrols the previous night to claim prime land. Many of these encounters gave rise to cuss fights, fist fights, and occasional gun fights as the homesteaders pushed toward their dreams of one-hundred-sixty acres of free land. Overnight the area billowed into a tented city of thousands, a city that some say was born grown and became known as Oklahoma City. Next to Oklahoma City, across the North Canadian River where it loops to the south and many homesteaders landed, sprouted Capitol Hill.

In the early 1900s, a bricklayer named George Owens purchased two lots at the edge of Capitol Hill. Using salvaged lumber from a relatives construction job, he built a twenty-by-twenty-foot box house for his wife Nellie and himself. There, they raised two children: their daughter Marguerite, and her older brother Melvin.

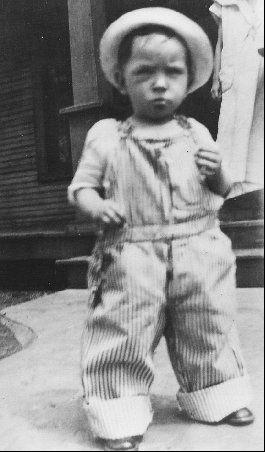

Melvin Owens, circa 1918

Melvin possessed an innate sense of adventure, and at Lee School in Capitol Hill in 1926, a single photograph sparked the point around which his life began to pivot.

Alaska..., his fourth-grade teacher had said.

That was the only word among the long string of others that caused ten-year-old Melvins slouch to straighten and his dusty leather shoes to shuffle and rest flat against the wood plank floor beneath his desk. He leaned over the geography book and eyed the photograph to which his teacher had referred. His hairblack as a mine shaftstuck out from the crown of his head where his mother had cut it too short.

Next page