When Abortion Was a Crime

To my mother, Susan Gardner, for her strength and creativity.

To my father, Phil Reagan, for his sense of adventure.

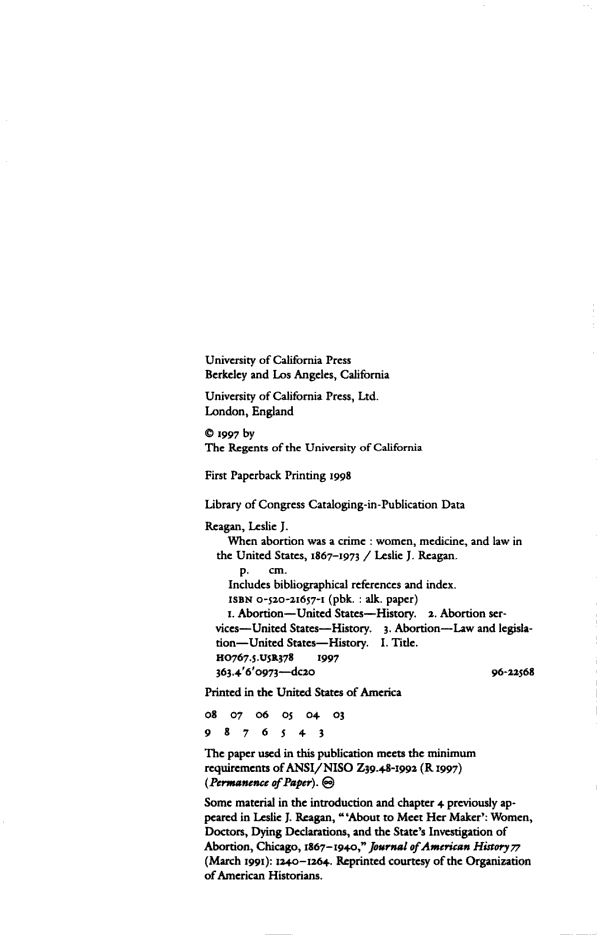

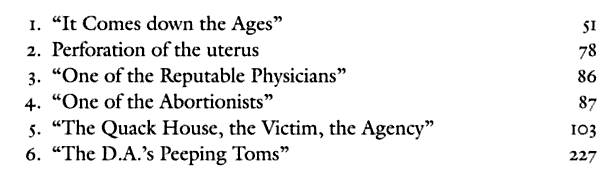

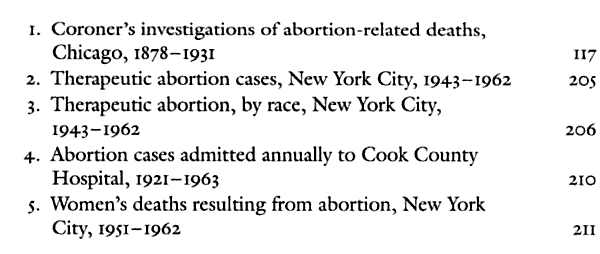

Illustrations

Plates

Figures

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to take a few moments and remember all of the enthusiastic support and assistance that I received as I worked on this book. Friends, family, teachers, colleagues, and many others have sustained me through the process.

I was fortunate to be part of the women's history program at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. This program, founded by Gerda Lerner, brought together an energetic and creative group of graduate students and faculty. Two excellent advisors, Judith Walzer Leavitt and Linda Gordon, encouraged and challenged me every step of the way. I am grateful for their guidance and friendship. I appreciate too the counsel of Gerda Lerner, Hendrik Hartog, Ronald Numbers, Vanessa Northington Gamble, and Carl Kaestle. Morris Vogel, Steve Stern, and the late Tom Shick encouraged me at an early stage.

Graduate students in the Wisconsin history department created an invigorating intellectual climate, which nurtured me and this project. Furthermore, their commitment to both outstanding scholarship and progressive activism is one I cherish. For all of their support, I thank Kathleen Brown, Eve Fine, Joyce Follet, Colin Gordon, Roger Horowitz, Nancy Isenberg, Marie Laberge, Nancy MacLean, Earl Mulderink, Edward Pearson, Leslie Schwalm, Doris Stormoen, and Susan Smith. I am particularly grateful to Kathy Brown, Joyce Follet, Leslie Schwalm, and Mary Odem, who remain engaged with my work, even by long distance telephone and often on short notice.

I appreciate the comments and encouragement of Allan Brandt, Anna Clark, Mary Fissell, Judith R. Walkowitz, and Danny Walkowitz. I am grateful to my colleagues in the Social History Group at the University of Illinois and to Diane Gottheil, Karen Hewitt, Evan Melhado, Jean Rhodes, Dorothee Schneider, Paula Treichler, Kathy Oberdeck, and William Munro for their suggestions on various phases of this project. I thank my research assistants, Lynne Curry, Mark Hemphill, and Rose Holz, for aiding me in the final stages of research.

Of critical importance are the librarians and archivists who facilitated my research. I thank Bob Bailey and Elaine Shemoney Evans at the Illinois State Archives, Lyle Benedict at the Municipal Reference Collection in the Chicago Public Library, Micaela Sullivan-Fowler, formerly at the American Medical Association, and Cathy Kurnyta, formerly at the Cook County Medical Examiner's Office. Jackie Jackson gave me a delightful home away from home when I did research in Springfield. Kate Spelman graciously offered legal advice. I thank the University of Illinois staff in history and medicine for their timely and friendly assistance. Editors and anonymous reviewers at the University of California Press, the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, and the Journal of American History have all offered helpful advice to make this book a better one. Jim Clark, Eileen McWilliam, Dore Brown, and Carolyn Hill at the University of California Press have been especially encouraging.

Many women and men, from clerks to professionals, volunteered their own abortion stories when they learned of my project and told me firmly that this was a book we "needed." Their belief in this project has always been important to me. I thank Susan Alexander and Sybille Fritzsche for sharing their memories of their legal effort to overturn the Illinois abortion law. It has been a pleasure getting to know them. I thank Peter Fritzsche for introducing me to his mother.

I have had the good fortune to have been granted vital financial support for the research and writing of this book. I am grateful to the Department of the History of Medicine of the University of Wisconsin Medical School for the Maurice L. Richardson Fellowships, the University of Wisconsin, Madison History Department, the American Bar Foundation, and the Institute for Legal Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison for crucial support as a graduate student. The Institute of the History of Medicine and the Department of History at Johns Hopkins University provided postdoctoral support. Since coming to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I have received funding for research assistance from the UIUC Research Board; a semester as a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study gave me time to write; and both of my departments, the Department of History and the Medical Humanities and Social Sciences Program in the College of Medicine, graciously granted leave to research, write, and complete my book. A National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine grant (grant number Ro1 LM05753), supported the final revisions of the manuscript. This book's contents do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine.

The support of family has been special. I deeply appreciate the interest that all members of all sides of my diverse familyGardners, Reagans, Schneiders, Edwards, Dejarnatt, Goodman, Kanefield, Spelman, and Brillingerhave shown in my book. Recently, it has been a pleasure to talk of the delights and difficulties of writing with Billy, David, Mom, and Dad. Zola and Irv helped me by sharing their thoughts. My late grandparents, Mercedes Philip Gardner and William Irving Gardner, had an abiding belief in the importance of higher education and conveyed their belief in me and my chosen intellectual challenges. I am sorry they cannot see this book.

I met Daniel Schneider as I was about to head for Chicago to do research. He has always been interested in this project, from hearing about my discoveries in crumbling legal records to discussing the book's structure. Daniel has generously read many drafts, given excellent editorial advice, and produced all of the figures for this book. For his enthusiasm, his thoughtfulness, and his help, I am deeply grateful.

At the time that abortion was becoming legal in this country, I'm not sure that I even knew what it was, but I remember a moment in the kitchen when I asked my mom about it. Her response, though of few words, and perhaps a bit embarrassed, firmly imparted the belief that women had to be able to control their reproduction and that, sometimes, they had to be able to have abortions. That brief, dimly recalled conversation, I have since learned from my research, was like many others that mothers and daughters, friends and family members had about abortion through the twentieth century.

Introduction

There would be no history of illegal abortion to tell without the continuing demand for abortion from women, regardless of law. Generations of women persisted in controlling their reproduction through abortion and made abortion an issue for legal and medical authorities. Those women, their lives, and their perspectives are central in this book. Their demand for abortions, generally hidden from public view and rarely spoken of in public, transformed medical practice and law over the course of the twentieth century.