ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

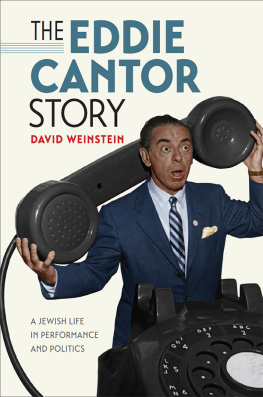

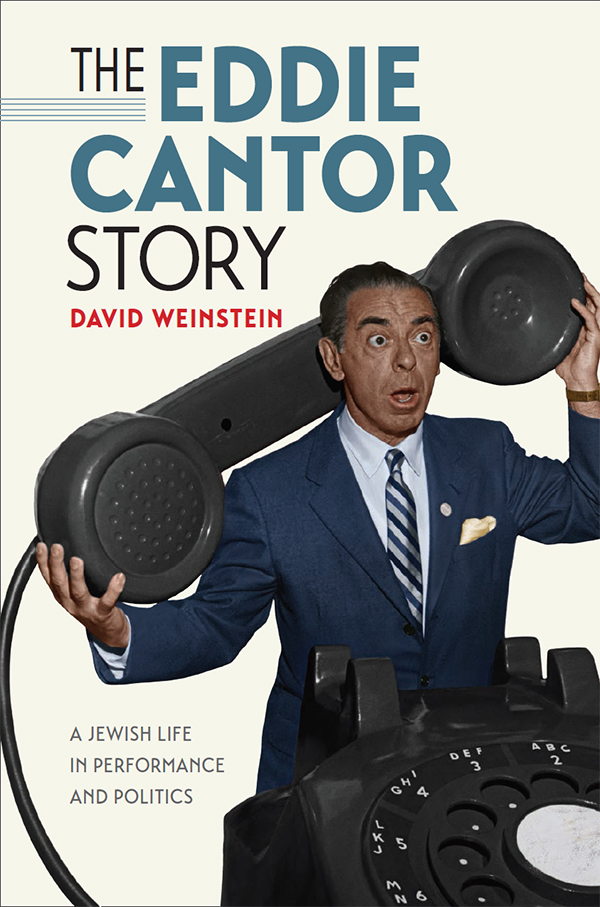

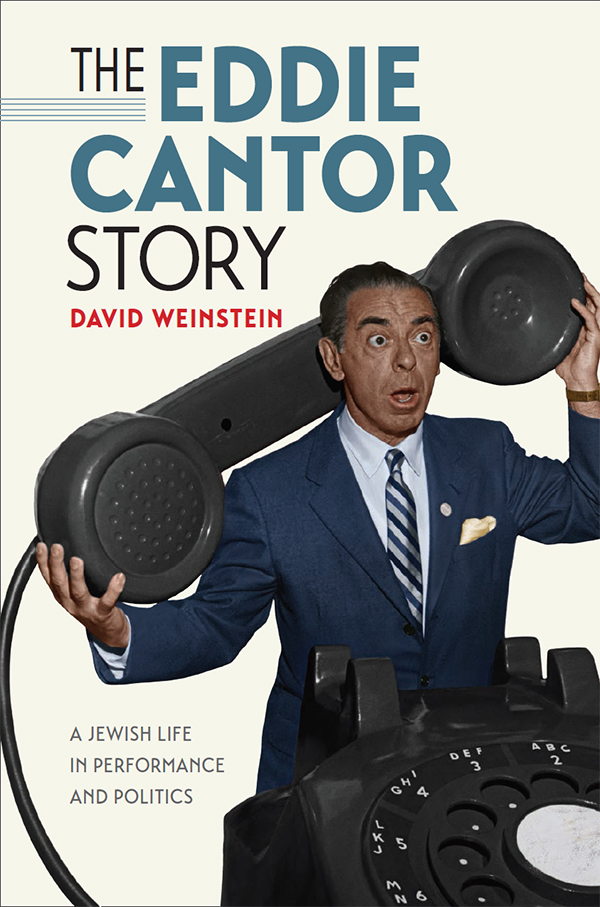

I never saw Eddie Cantor perform live. He died a few years before I was born. I first experienced Cantor through The Colgate Comedy Hour programs on which he starred during the early 1950s. I found a few of these shows on videotape while I was researching my previous book: The Forgotten Network: DuMont and the Birth of American Television (2004). I had associated Cantor primarily with vaudeville and Broadway of the 1910s and 1920s. I was surprised to see Cantor headlining a popular television program many years after his vaudeville days. Even though he was a little past his prime on The Colgate Comedy Hour, Cantors charisma, energy, and ability to connect with audiences impressed me. I wanted to know more about this performer. After I finished The Forgotten Network, I turned my attention to Cantor.

I immersed myself in primary materials and scholarship covering more than seventy years of American social, cultural, and political history. Fortunately, I had many wise mentors and experts to guide me in this research and writing. I am especially grateful to the following people for reading portions of this manuscript, sending me archival treasures, and sharing their vast knowledge about everything from Lower East Side history to the modern publishing industry: Margaret Bausman, Lila Corwin Berman, Hasia Diner, Tom Doherty, Brian Gari, Grace Hale, Jeff Hardwick, Daniel Horowitz, Ari Y. Kelman, Alan Kraut, Lisa Moses Leff, David Margolick, Jonathan Markovitz, Michael McGerr, Cynthia Meyers, Howard Pollack, Jennifer Porst, Kathy Fuller Seeley, Lauren Sklaroff, Sean VanCour, Jennifer Hyland Wang, Steve Whitfield, and the Wolkin family.

I benefited from opportunities to deliver talks about Eddie Cantor and participate in seminars hosted by the following groups and organizations: the American University Judaic Studies Program, the Association for Jewish Studies, the BaltimoreDC Media Studies Group, Bnai Israel Congregation (Rockville, Maryland), the Radio Preservation Task Force, the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History Colloquium, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. I thank the coordinators, fellow panelists, and attendees of these programs for engaging in lively discussions about Eddie Cantor and his world.

I am lucky to work with a great group of supportive friends and colleagues at the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), a vibrant intellectual environment. In addition, the agencys Independent Study, Research, and Development (ISRD) program granted me time to conduct archival research. The views that I express in this book do not represent those of the NEH or the federal government.

A Montgomery County (Maryland) Arts and Humanities Council grant facilitated a valuable research trip to Los Angeles and San Francisco.

In writing The Eddie Cantor Story, I had the opportunity to explore terrific libraries and archives. Thanks to the NEH Library (Donna McClish); the American Jewish Historical Society (Boni J. Koelliker and Susan Woodland); Oviatt Library Special Collections and Archives, California State University, Northridge (David Sigler); the Library of Congress Recorded Sound Research Center (Bryan Cornell, Karen Fishman, and David Sager); Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University (Clay Stalls); the National Center for Jewish Film (Lisa Rivo); the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (Annemarie van Roessel); the Paley Center (Mark Ekman and Jane Klain); SAG-AFTRA (Valerie Yaros); the Shubert Archive (Maryann Chach and Sylvia Wang); the Film and Television Archive, University of California, Los Angeles (Mark Quigley); Library Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles (Annie Watanabe-Rocco); the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley (Chris McDonald); Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries (Michael Henry and Chuck Howell); the Wisconsin Center for Film and Television; and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (Gunnar Berg and Fruma Mohrer). Special thanks to Milt Larsen for generously making his personal Eddie Cantor collection available to me and to Carol Marie for her kind and resourceful work in uncovering and sharing so many great materials from this collection.

An earlier version of was previously published in American Jewish History (December 2010). Thanks to the journal and to Dianne Ashton for her editing of this essay.

Phyllis Deutsch at University Press of New England/Brandeis University Press is a great editor. I especially appreciate her enthusiasm for the project, wise suggestions for revision of the manuscript, and expert guidance through the different stages of publication. Thanks, also, to the skillful team that prepared the manuscript for publication, including the production editor, Susan Abel, and the copyeditor, Elizabeth Forsaith.

Sleater-Kinney, the Mekons, Neil Young, and the Fastbacks provided a steady soundtrack when I needed a break from Tin Pan Alley. In addition, this music inspired me to think more deeply about fandom, celebrity, nostalgia, and other concepts that are central to this book.

Special thanks to Ellie Weinstein and Sara Weinstein for their curiosity about Eddie Cantor and recommendations for alternative titles (The Jewish Cantor received strong consideration). I also thank Sara and Ellie for showing me the joys of being a dad and for enticing me away from Eddie Cantor.

Through my many years of writing this book, Rachel Weinsteins questions, ideas, comments, and copyediting prompted me to clarify my thinking and writing. Rachels most important contributions to this book are harder to describe. I thank Rachel for her love, support, encouragement, and willingness to choose family vacation spots based on their proximity to Eddie Cantor landmarks and archives.

This book is dedicated to the memories of Susan Flatt and Steve Weinstein.

IMMIGRANTS, CRIMINALS, AND ACTORS (18921908)

T he Lower East Side of the 1890s was a brutal neighborhood, but Isidore Izzy Iskowitz had little say in where he spent his childhood. Iskowitz, who later become known as Eddie Cantor, was born in a small Eldridge Street apartment on January 31, 1892.

When Meta and Mechel arrived in New York, they reunited with two of Metas brothers who had immigrated earlier. Metas mother, Esther Kantrowitz, left Russia to join her children in 1891, when Meta was pregnant with Eddie. The Kantrowitz familys life in America was difficult and at times tragic. Eddies mother, Meta Kantrowitz Iskowitz, died of lung disease on July 26, 1894, when her son was two years old.

Is the story true? Possibly. Mechel Iskowitz may have died of pneumonia in late 1894 or early 1895, as Cantor later recounted. Or Mechel may have abandoned his son and built a new life elsewhere. In addition to providing a sympathetic description of his fathers final moments, Cantor portrayed Mechel as a lovable neer-do-well who had

Given the lack of extant documentation, it is impossible to ascertain when and how Cantors father died. More broadly, most of Cantors early life must remain a mystery to historians. Our knowledge is filtered through Cantors memories and his self-interest as a celebrity who carefully crafted his public image. Except for a few stray census records, there are no primary sources or even interviews with people who knew Cantor as a child to confirm the actors accounts of his coming-of-age in New York. Cantors autobiographies, two essay collections, interviews, and comedy sketches about his youth, created and modified over his years in the spotlight, mix fact with fiction. His entertaining, surprising recollections of his early life should not be taken too literally; however, these stories illustrate how Cantor saw himself and how he wanted the public to see him. Cantor used childhood anecdotes to explain and amplify different aspects of his star persona. He highlighted his rise from poverty, identity as a Lower East Side Jew, familiarity with violent street life, and practicality in pursuing a career in show business.

Next page