My sincere thanks to the many people without whose help this book would not have been possible: photographers Reg van Cuylenburg and Richard Cheek; Daniel Lohnes and William Blandford of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities; Joel Kopp of America Hurrah Antiques; Bates Lowry of the University of Massachusetts, Boston; and the following rug hookers and teachers: Patience Agnew, Anita Allen, Betty Asquith, Anne Ashworth, Alice Beatty, the late Milda Berry, Bernice Bickum, Ethel Bruce, Pauline and William Burdick, Virginia Burgeson, Viola George, Ruth Gillette, Hallie Hall, Ruth Hall, Lydia Hicks, the late Ruth Higgins, Margaret Hooper, Louise Johnson, Mary Langzettel, Priscilla Lindley, Polly Merrill, Elizabeth Palmer, Marianna Sausaman, Abby Simms, Grassie Ward.

J. M.

Cushings Perfection Dyes, color-coordinated fabric swatches and Craftsman Studio patterns for rug hooking are available from W. Cushing & Co., P.O. Box 351, Kennebunkport, Maine 04046.

1 The American Tradition of Rug Hooking

Rug hooking reached a creative peak in early nineteenth-century America (in both New England and the Canadian Maritime Provinces), although both skilled and unskilled hookers were handicapped by a basic lack of materials and had to rely on their own ingenuity. Before the widespread availability of burlap (after 1850), feed sacksafter they were washed, stretched, and piecedwere frequently used as the foundation material. The fabric to be hooked into the foundation came primarily from clothing no longer usable; the otherwise-worthless woven materials were washed, sorted, and then colored in homemade dyes extracted from local plants (yellows were obtained from golden rod, marsh marigold, sumac, oak, and sunflower; greens from mint, ash, and smartweed; reds from cranberry, sumac, bloodroot, dogwood, alder, and elm; blues from grape, sycamore, and larkspur; browns from walnut, butternut, and alder). The dyed materials were then cut into narrow strips to be worked into the foundation using hooks fashioned from nails, bone-handled forks, or whatever else was readily available.

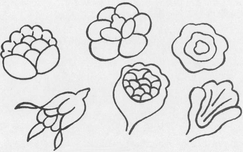

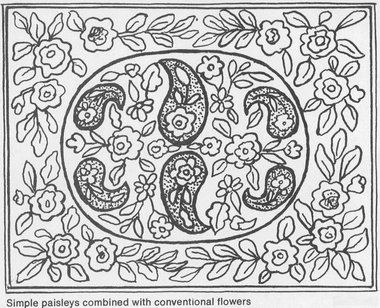

For some, creating a design was most likely a difficult task, although husbands and children undoubtedly took a keen interest in the planning of the current mat design, contributing ideas and suggestions. Others adapted bits of embroidery or a treasured piece of decorated china. Most early rug hookers, though, relied on their surroundings for inspiration. Houses, barnyard scenes, a cat frolicking with her kittens, dogs, horses, hens, roosters, a horseshoe for good luck, and the always beloved flowers from the summer gardenthese, recreated in simple form on the burlap, became abstractions of the real blossoms, beautiful in their own way.

No fancy methods of transferring the designs for the early rug hookershe took a piece of charcoal and drew directly onto an old feedsack or other foundation material. This freewheeling method accounts for the simplicity and naive charm which characterizes so many of the old rugs. Many a strange-looking animal was the result of a freehand attempt to portray some barnyard creature or favorite pet. Often, most unlikely objects were combined in these primitive designssuch as horses, birds, trees, stars, and crescent moonwith no attempt to show proper size relationship or perspective. But as amusing as these early designs are, they all clearly reveal the personality of the creator; they were truly a means of self-expression for the maker and as such have great charm and individuality.

Rug hooking was a craft confined not only to women. Sailors frequently hooked rugs on their long sea journeys; they used canvas as the foundation material and short strands of yarn or rope. Full-rigged ships, anchors, and whaling scenes were favorite designs. It is easy to imagine the sailors wives or sweethearts, inspired by these efforts, taking to the craft with enthusiasm.

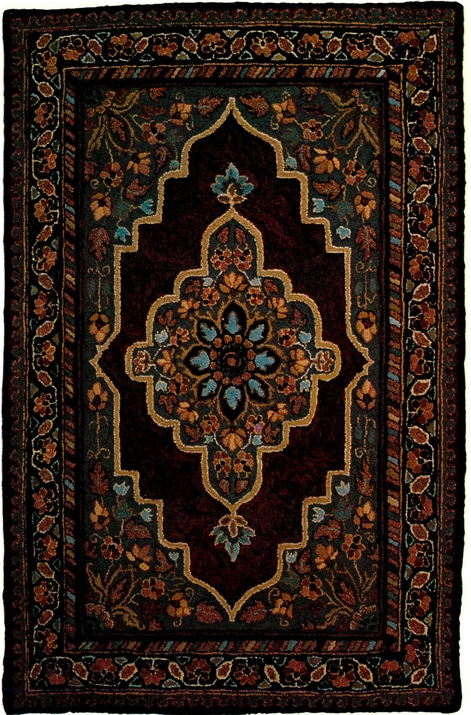

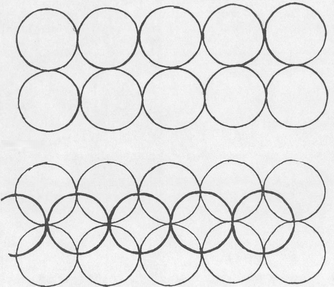

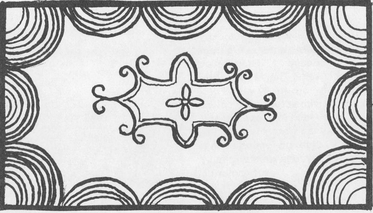

Geometric patterns have always been popular with rug hookersprimarily because they are simple to design. Early rug hookers used the burlap mesh as guidelines, drawing directly on the burlap with charcoal or using everyday objects as templates. The kitchen plate, for example, was a popular designing aid; it was drawn around as many times as necessary for an overall design (the circles side by side or overlapping) or it was used as a stencil to provide interesting borders. The antique rug on page vii, from Beauport, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, is a stunning example of how effective a simple circular design can be. Geometric designs were not only comparatively simple to design, but could also be very attractively hooked with what rug hookers call hit-or-miss: multicolored leftover materials hooked in without further dyeing. Frequently, the different colors and assorted textures of leftover wools created a fascinating effect despite an otherwise dull, uninspired design.

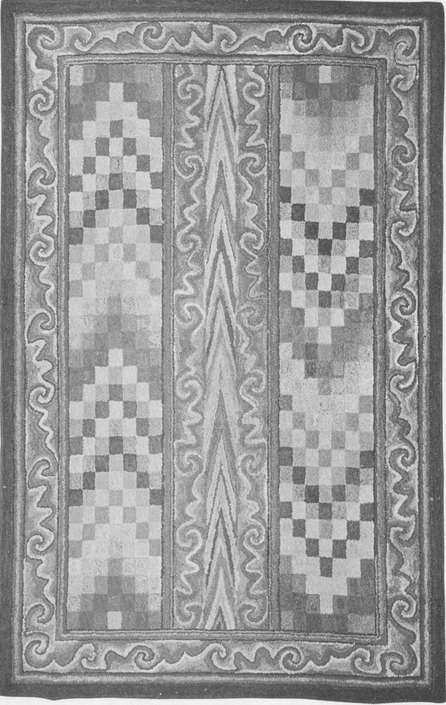

Checks and arrows in a mostly geometric antique rug from Beauport, Gloucester, Massachusetts. The basic motifs, in panels, are subtly varied and combined with scrolls. The colors have faded to appealing soft tones, but the vibrant hues of the back of the rug remind us that many early rugs were originally very colorful.

(Courtesy Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities) Illustrated on color plate A.