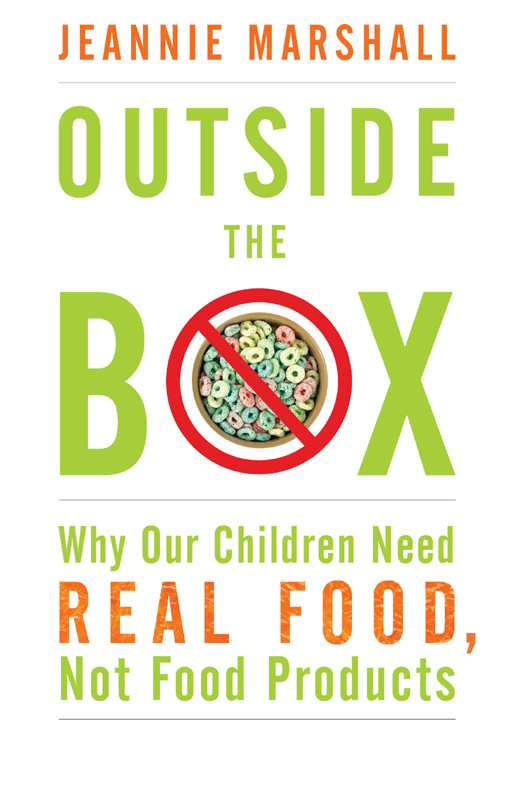

PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright 2012 Jeannie Marshall

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2012 by Random House Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

www.randomhouse.ca

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Marshall, Jeannie

Outside the box : why our children need real food, not food products / Jeannie Marshall.

eISBN: 978-0-307-36005-2

1. ChildrenNutrition. 2. ChildrenHealth and hygiene. 3. Convenience foodsHealth aspects. 4. Food industry and tradeHealth aspects. 5. LifestylesHealth aspects. I. Title.

RJ206.M37 2012 613.2083 C2011-904613-X

Cover design by Leah Springate

Cover images: (cereal) Louella38/Dreamstime.com;

(orange) Ppy2010ha/Dreamstime.com

v3.1

For James and Nico.

My fellow adventurers.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

WHATS INSIDE THE BOX?

O n a typical Saturday morning in Rome, my small son, Nico, and I wander through our local, outdoor food market. Hes eating a few sections of a blood orange that a fruit vendor gave him. Its early winter so were looking over the red and green cabbages, the artichokes with their long stems, and the craggy, dark green bunches of Tuscan kale. Im imagining the kale for lunch, prepared the way Carlo, the farmer who grows many of the vegetables we eat, told me to do it one of the first times I bought somecooked in water until tender, then sauted for a few minutes in a pan with some olive oil, sliced garlic and a little salt, and finished off with a squeeze of lemon. Then Nico spots someone snapping the ends off green beans. He likes them steamed and dressed with olive oil and lemon. Dai mi mezzo chilo, he tells her. She laughs at this bean-loving child and hands him a few fat, red Sicilian grapes, likely the last of the season, to eat while she weighs the beans. He thanks her and asks how much longer he has to wait until its cherry season again. We carry on like this, buying what we need for the next few days and indulging in a few whims here and theresome arugula for a pesto, and some wild mushrooms for a risotto.

I like coming here in the mornings. It reminds me that food doesnt need to be complicated. Nico loves being here because it gives him some say in the food we buy, and because someone always hands him something good to eat, like the orange, the grapes, and those memorable cherries in summer. The choice of treats is between a sweet mandarin orange and maybe a lumpy rennet apple. Nothing is packaged, there is only food here in this market, most of it requiring washing and chopping and cooking.

We might stop at the butcher shop on our way home. Ill ask for a piece of pork to roast, and the butcher will point to a few different parts of the portion of a pig lying in the refrigerator case, then cut the chosen piece from the animals body and tie it with string and sprigs of fresh rosemary. There is no attempt to hide the fact that what Im buying is a piece of flesh, and this uncomfortable knowledgenot to mention the high pricekeeps me from buying and eating this flesh more than once or twice a month, which is good for our health. Ill cook it for dinner on Sunday as he suggests, browned in a pot with onions, celery and carrot, and then simmered in red wine and vegetable broth with garlic cloves and rosemary.

This is exactly what I thought food shopping would be like in Rome when I moved here from Canada in 2002: market stalls overflowing with fresh, local produce, people shouting buon giorno to each other, blood-streaked butchers who know everything about the meat they sell, including what the animal ate and where it died. The market has given me an education in Roman cooking.

When our son, Nico, was born nearly three years into our stay, I began to see how Italian parents introduced their children to real foods instead of the packaged food products for babies and children that I was used to seeing in North American supermarkets. I watched mothers feeding their babies and toddlers healthy, flavourful foods such as savoury beans cooked in herbs, and the all-important pasta with numerous variations on vegetable sauces. I loved that you could take a baby or toddler into a really nice restaurant and that you would be treated like a royal family, complete with special tours of the kitchen and dining room for the little prince or princess. But as Nico began school I realized that he and his Italian peers were being waved off the traditional path of healthy food and directed toward a new food culture, one far too similar to the one I thought I had left behind in North America.

It is heartbreaking to see Italian children eating hot dogs, hamburgers, french fries, potato chips, chocolate bars and candy instead of seafood risotto, spaghetti al rag and green beans cooked in tomatoes. Rather than having a ceremonial drop of wine in a glass of water at Sunday lunch, children are drinking Coke and Pepsi. As my old culture threatens to overtake my new culture, I wonder if these children will be able to carry on the traditions of Italian cooking and the Italian way of eating.

Of course this change in childrens eating habits is happening all over the world, and childhood obesity statistics are growing even in the poorest countries. Long-standing food cultures, traditions that have provided pleasure and good health to people all over the globe, are disappearing because of this rapid change in childrens eating habits. Children are key to changing a culture for better or worse. But children need help from the adults in their homes and communities. If children are to carry on traditional food cultures or reinvent them in places where they dont exist, they need to eat real food and not food products.

CHAPTER ONE

DISCOVERING A FOOD CULTURE

The Adventure Begins

P eople come to Italy for the food. They also come to see the Colosseum and the Sistine Chapel in Rome, the Uffizi Gallery and the statue of David in Florence, and Saint Marks Basilica and those handsome gondoliers in Venice. But I think far fewer of them would come to Italy if there were not such good food to eat between the churches and galleries. All this can lead some people to dream of living in Italy. Its usually a dream with roots in a long-ago visit on a hot afternoon, a spring day spent lost and wandering narrow cobblestoned streets lined with ancient crumbling buildings covered in a purple haze of thick wisteria vines. The late afternoon light falls softly on the ochre and pale yellow palazzi; the cloudless sky seems blue with a touch of lavender. Inevitably, in this dream or hazy memory, there is a waiter in a crisp white apron. Prego, he says, sweeping his open palm invitingly toward a table for two set against a vine-covered wall in the shade with a view of pedestrians strolling past. Its late afternoon but too early for dinner. You stand there, wondering whether to stop or keep walking, when he offers you a glass of Franciacorta. You give in and sit down. You taste one of the fat, briny olives the waiter puts on the table, and then you sip the cool, bubbly, Champagne-like wine from the mineral-rich soil of Lombardy, and you cannot believe how gentle, how fruity, how sophisticated and utterly unique it tastes. You put away your guidebook and your map, and you stop trying to remember which emperor did what. You chat with your companionthe one you were arguing with barely a half hour earlierabout what you have seen, how different it is from your daily life, and how you would like to take some of this tranquil feeling, this mingling of heart-stopping beauty and fizzy wine, home with you.