A huge thank you, Eliana, for your pioneering work in articulating posttraumatic play. I remember the first time I heard you speak 20-some years ago: your heart, knowledge, and passion painted a path for my growth. Your voice has continued to be the most influential in my conceptualization of trauma work with children and families, and I am honored to have you add your voice to this book.

I am indebted to so many others who have influenced my thinking and shaped my approach. These influences include Charlie Schaefer, Garry Landreth, Sue Bratton, Heidi Kaduson, David Crenshaw, Phyllis Booth, Evangeline Munns, Joyce Mills, Linda Homeyer, Rise van Fleet, Athena Drewes, and Rick Gaskill, to name a few. As the field of interpersonal neurobiology has expanded, I have gained depth of understanding and augmented articulation from the work of Dan Siegel, Bruce Perry, Bessel van der Kolk, Alan Schore, Stephen Porges, Bonnie Badenoch and Theresa Kestly.

Thanks to my play therapy tribe. There are too many to name, but you know who you are! A special thanks to my play therapy womens writing retreat groupClair, Sueann, Jess, Angie, and Hollyfor carving out time and space for writing and laughing.

Thanks to the team that has helped me build Nurture HouseLinnea, Kristen, Eleah, Elizabeth, Amy, Eric, Jenny, Kate, Jess, Shelby, Bethany, and Stacey, to name a few. They have grown with me, encouraged me, and held down the fort when I am off gallivanting.

Lastly, my deepest gratitude for my best friend and partner in all things, Forrest. Thank you for taking up the slack again and again with grace and strengthas a parent and as tech supportand for being the love of my life and my biggest encourager. Thank you, Sam, Madison, and Nicholas, my sweet ones, for bringing me hugs, snacks, silly songs, encouraging notes, and for giving me belly laugh breaks from the writing.

1

Titration in Trauma Work

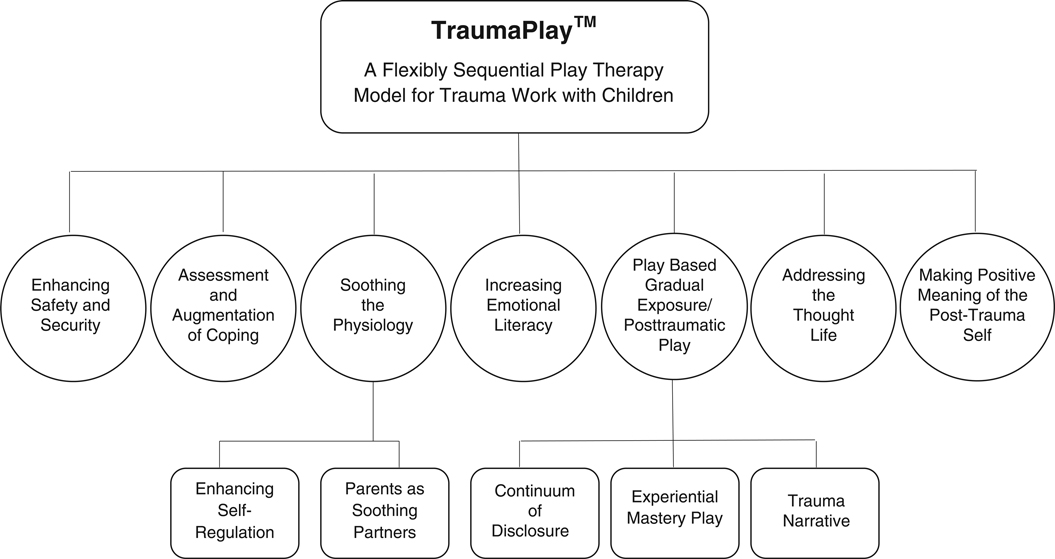

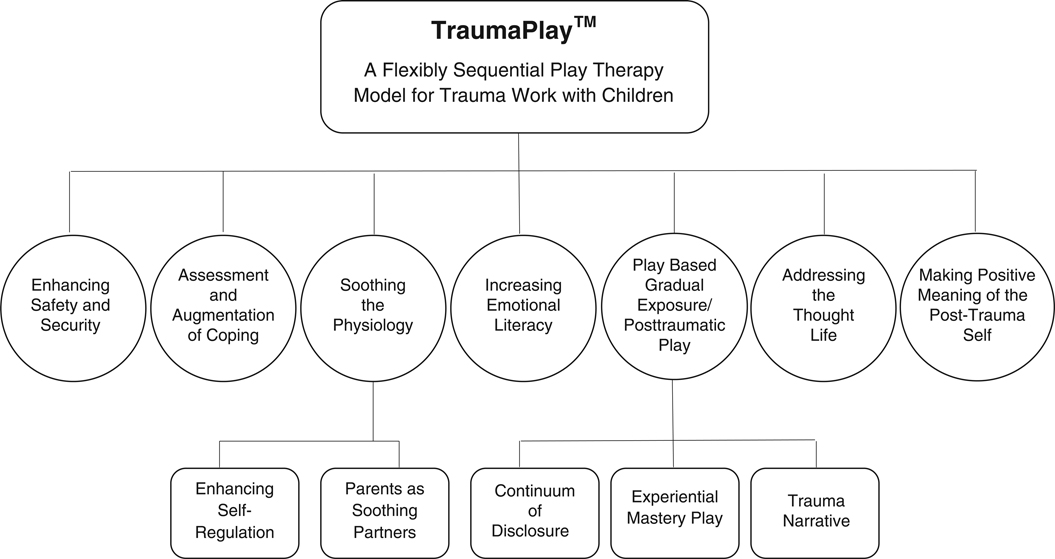

This project evolved as a response to repeated requests from clinicians who are familiar with the Flexibly Sequential Play Therapy (FSPT) trauma model, outlined in Play Therapy with Traumatized Children (Goodyear-Brown, 2010), to more fully explore the nuance of how we help children move toward and away from trauma content to create the story of what happened. The overarching goal of the work is to leach the emotional toxicity out of the childs experience so that it can be integrated into a healthy sense of self. This model, formerly known as FSPT, has been renamed TraumaPlay in order to give more clarity to clinicians and clients alike. TraumaPlay is components-based and allows for a variety of interventions to be placed along a continuum of treatment, depending on which treatment goal is actively being addressed. Goals in the early phases of treatment include building safety and security, addressing and augmenting coping, soothing the physiology, enhancing emotional literacy, and helping parents be better partners in regulation while offering additional caregiver support to help them hold the hard stories of the children in their care. The middle phases of treatment provide some form of play-based gradual exposure that may include the continuum of disclosure, experiential mastery play, and/or trauma narrative work. The final phase of treatment is helping the child and family make positive meaning of the post trauma self.

When to invite children to go deeper, when to respect their defenses, when to acknowledge their retreat, when to celebrate that they have come to the end of what they can approach right now, and how to support their exposure work are questions with which both beginning and seasoned clinicians wrestle. An attuned trauma therapist is deciding, sometimes on a moment-to-moment basis, when to invite children out of stuck places, when and how much to push up against avoidance symptoms, when to witness their posttraumatic play (Gil, 2017), and when to support the need to simply rest. This volume is meant to expand significantly on the nuance of these questions while offering a new tool for thinking about the mitigators of a clients approach to hard things.

If you work with traumatized children regularly, my guess is that you have already found yourself in a playroom environment with a child where you have been unsure when to offer invitations to further explore the traumatic event and when to allow the play to do its own healing work. As I train people both here and abroad, the struggle I hear clinicians wrestling with revolves around the question of when, how often, and how directly do I invite children to explore the trauma content in order to bring more coherence and when do I create a space of respite, mindfulness, and the simple and powerfully healing enjoyment of play? If we neglect the avoidance symptoms of posttraumatic reactions, we inadvertently collude with the trauma itself, communicating to the child that it is indeed too big and scary to be approached. If we push a child too hard or too fast, we can cause iatrogenic effects, flood them with anxiety, and shut down their healing process.

Another way this question gets put to me in training sessions is, when do you lead and when do you follow? The question is critically important and always excites me because the clinician asking is wanting to follow the childs need rather than becoming dogmatic about either following the childs lead or directing the therapeutic interactions in the room. A third way this question is asked is as follows: when does the therapist invite the child/family into new kinds of interaction and when does the therapist wait to be invited? Moreover, how do we extend moments of therapeutic work or help open and close circles of communication? Sometimes this question is not specific to the traumatic event but may be asked in relation to other goals of treatment, ones that would be considered symptomatic of the trauma itself, such as self-regulation abilities, hyperarousal symptoms, and a childs ability to connect with others.

My response to this question of when to lead and when to follow, when to be more or less directive, is unpopular in our current protocolized culture: it depends. Beginning clinicians really do not like this answer, as the clearly defined steps of a protocol are soothing to them. As we grow, we become more comfortable with ambiguity and with trusting the process, but it remains important, even for seasoned clinicians, to ask this same question of when to lead and when to follow in a present-minded way in each and every session. One of my goals in supervision is to help clinicians become more comfortable with not having a definitive answer for what is needed per protocol so they can hone their ability to follow the childs need from moment to moment. My goal is to help clinicians nurture the nuance in trauma work with children and families.

Nurturing the Nuance

Nuance is necessaryarguably in all forms of therapy and most certainly when using play therapywith traumatized children and families. I have learned this lesson by going too slowly with a client systemnot offering enough invitation to change or not providing enough strengthening of the muscles that hold hard things. I have also failed in the opposite extreme by attempting to take a child too quickly toward hard things. My concern about treatment becoming cookie cutter-ish applies to my model as much as to any other model of treatment. The flow of the treatment goals codified in TraumaPlay is pictured in ).

Flowchart of TraumaPlay, Formerly Known as FSPT