IMAGES

of America

WHITTIER

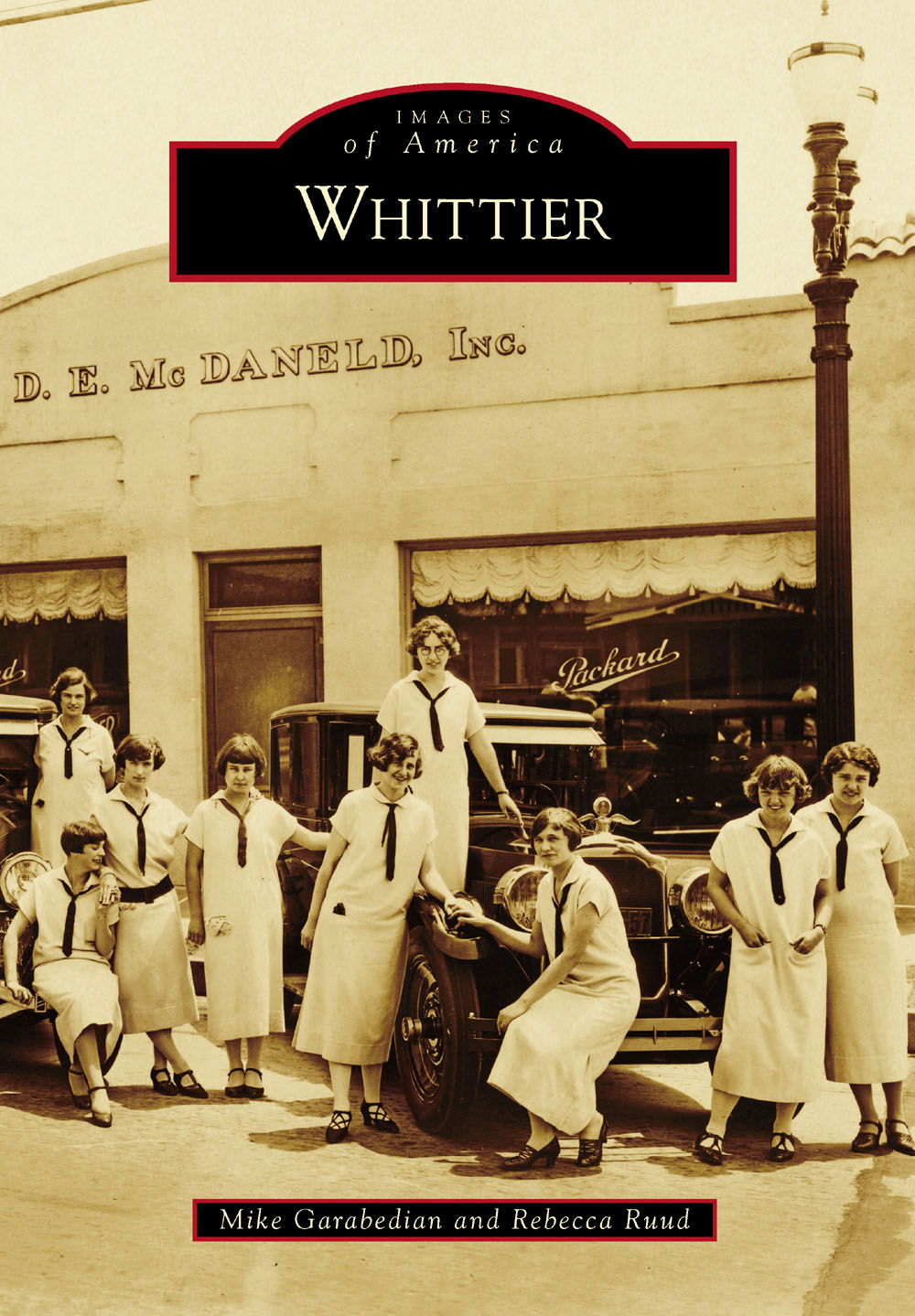

ON THE COVER: The D.E. McDaneld automobile dealership was located on the corner of Hadley Street and Newlin Avenue. In the photograph are iconic Packard luxury automobiles and the 14 members of the 1925 Whittier College girls glee club. (Whittier Public Library.)

IMAGES

of America

WHITTIER

Mike Garabedian and Rebecca Ruud

Copyright 2016 by Mike Garabedian and Rebecca Ruud

ISBN 978-1-4671-3429-3

Ebook ISBN 9781439655832

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015943285

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

With sincere gratitude, this book is dedicated to Ruth Webster Lynch (August 1, 1951April 8, 2015), longtime Whittier resident, reference librarian for the City of Whittier, and local historian; without her initial help and encouragement, this book would not exist.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All books are the product of a community effort. This publication would not have been possible without the generous support and encouragement of many Whittier community members, but we want to name a few whose contributions to the work were particularly exceptional.

We want to thank Hannah Colvin, of the Whittier Museum, and Erin Fletcher Singley, of the Whittier Public Library, for assistance with photograph duplication, reference help, and solving more than a few mysteries, but also for all the hard work these professionals do to share Whittiers history with researchers and patrons. Thanks also to Whittier Historical Society president Tracy Wittman and Whittier Public Library director Paymenah Maghsoudi for being gracious and helpful hosts and providing us access to their collections.

We want to thank filmmaker and historian John Garside, a shepherd through the early history of Whittier, whose knowledge of the city and excellent Whittier documentaries (all available for free online) informed many of our decisions. Thanks to Steven Otto for helping us spread the word about the book and providing feedback about the images we discovered; thanks, too, to the many members of the Facebook page he administers (Whittier, California - Our Hometown) for providing invaluable information about more recent Whittier history and helping to answer many of our questions about people and places that are no longer here. And thanks to Kim Wicker and Judy Jansen for providing insights about and access to photographs of Whittier in the mid-20th century and the years leading up to its centennial.

We want to thank our studentsin particular Gawen Grunloh, Alejandra Gaeta, and Priscilla Gutierrezfor their assistance, and our colleagues, the staff of Wardman Library at Whittier CollegeCindy Bessler, Shezad Bruce, Sonia Chaidez, Anne Cong-Huyen, Laurel Crump, Joe Dmohowski, Kathy Filatreau, Chris Greenwood, Mary Garside, John Jackson, Steve Musser, and Nick Velkavrhfor their support, advice, patience, and friendship while we were writing this book. Thanks also to our families and non-work friends for their continued encouragement.

Finally, we want to thank our editors at Arcadia PublishingHenry Clougherty, Lily Watkins, Alyssa Jones, and Sara Millerfor their wisdom, keeping us on track, and helping us establish deadlines (and for their understanding when we sometimes missed those deadlines).

For the purposes of attribution, the courtesy lines at the ends of captions accompanying images from the collections of the Whittier Public Library are abbreviated as WPL; those from the collections of the Whittier Historical Society at the Whittier Museum are abbreviated as WM; and those from the Whittier College archives are abbreviated as WC.

INTRODUCTION

Hiking in the canyons or up the slopes of the Whittier Hills still gives a sense of what this land was like before Quakers founded their city of dreams here in the late 19th century. Oak and sycamore trees flourish alongside seasonal creeks and on the hillsides, while wild mustard transforms the place into a shockingly vibrant yellow meadowland in rainier springs. On a clear day, the sun glints off the Pacific Ocean, 20 miles away, while to the north, the San Gabriel Mountains rise majestically from the valley floor. On the southeast-facing slopes of the hills, where the Quakers settled, ocean breezes keep the land cooler than the flatlands below, while the hills themselves act as a kind of wall to prevent severe winter frostsa climatic feature appreciated by Whittiers first citrus farmers and touted by the citys earliest boosters.

The first people to settle in the area that would become Whittier were the Tongva, Native Americans later known by the Europeanized name Gabrieleo after Mission San Gabriel Arcngel, which was originally located in todays Whittier Narrows on a small tributary of the San Gabriel River. The Tongva moved into the Los Angeles basin from Southern Nevada some 3,000 years before they encountered Spanish explorers in the region in the 1540s, when their population may have reached 10,000. Before European contact, the Tongva had developed a society comprising hundreds of independent villages scattered across the basin and generally close to permanent sources of water like the Los Angeles, Santa Ana, and San Gabriel Rivers. Those who settled near the San Gabriel River in what would become Whittier called this land and their village Sejatngna.

What happened to Sejatngna and the Tongva near Whittier is a story no less tragic for its familiarity. Following the arrival of Spanish missionaries, led by Fr. Junpero Serra Ferrer, and the founding of the San Gabriel mission in 1771, the several-millennia-old lifestyle of the Native Americans began to disintegrate. Forced conversions, subjugation, compulsory relocation to the mission complex, and the institution of slave labor decimated the Tongvan population; European diseases killed still more. Mission priests made subjugated Tongvans plant European grains, New World vegetables, and the first citrus trees in California near the mission complex. There, fertile soil and clement weather, combined with a steady supply of water from the river, made the area a center of agricultural production. However, in 1776, a flood wiped out the mission crops and the complex itself, compelling the Spanish colonists and their Tongvan subjects to relocate some five miles upriver to the missions current location in present-day San Gabriel. By the start of the 19th century, a few small, scattered, and ramshackle Tongvan encampments still existed along the San Gabriel River south of the old mission site, but Sejatngna and Tongvan society were effectively gone forever.

In 1784, Gov. Pedro Fages granted former Spanish soldier and Gaspar de Portola expedition member Jos Manuel Nieto provisional use of the 300,000 acres between the Santa Ana and Los Angeles Rivers from the San Gabriel mission down to the Pacific Oceanthe largest Spanish land grant in California. However, San Gabriel mission priests contested the award, suggesting it encroached upon property that was rightly theirs. After a protracted legal battle, Gov. Diego de Borica reduced Rancho Los Nietos to about half its size, and the Rancho Paso de Bartoloa new grant comprising present-day Montebello, Pico Rivera, and Whittieragain became mission property. After the secularization of the missions in 1835, the Mexican government awarded Rancho Paso de Bartolo to Juan Crispin Perez, a manager at the mission complex. Perez used the grant for its intended purposethe cultivation of livestockand grazed herds of cattle and sheep on the flatlands and hillsides of the area that would become Whittier.

Next page