Contents

Guide

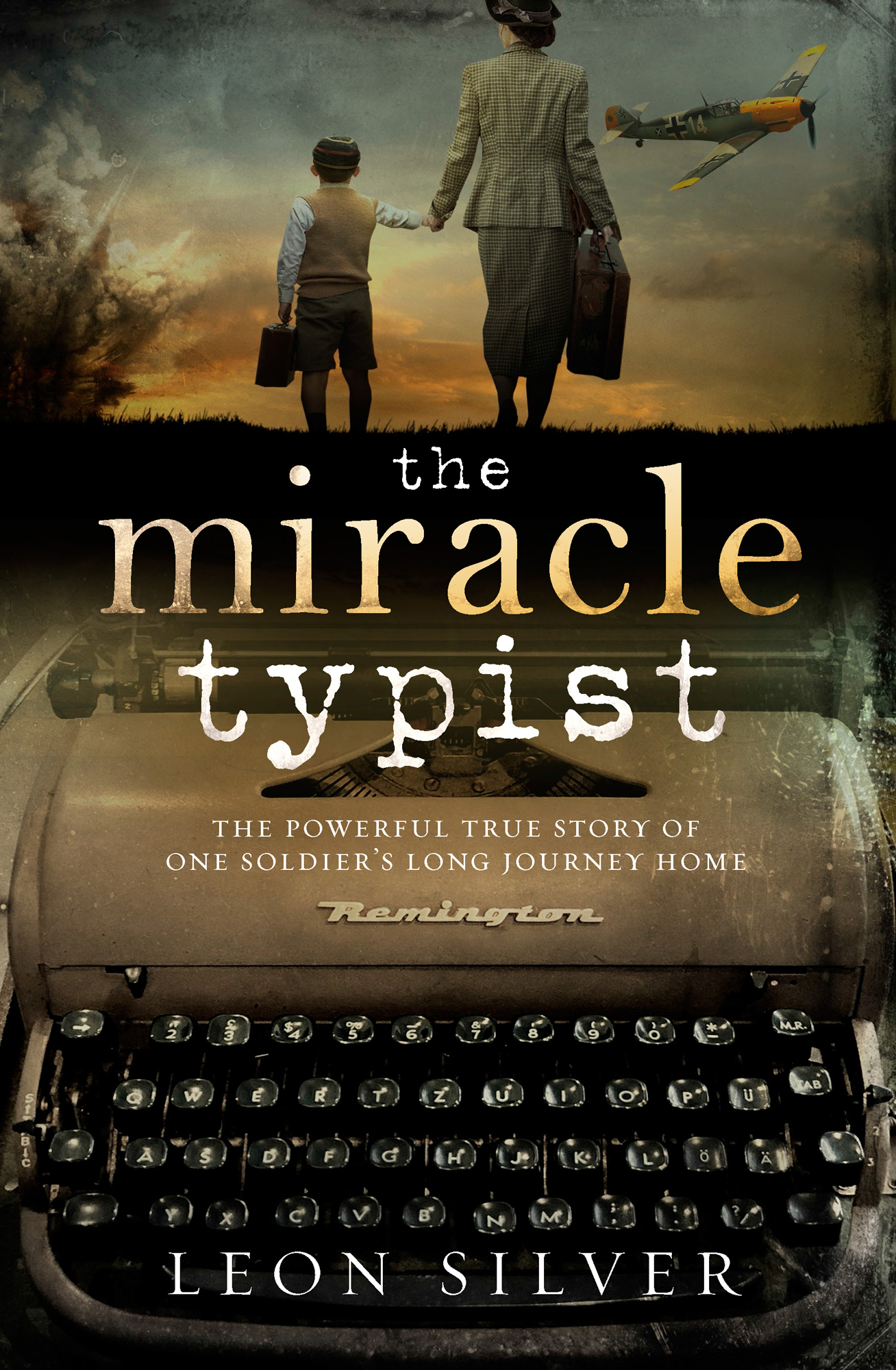

This book is dedicated to Tolek Klings, my father-in-law, mentor and friend, with love and gratitude.

A soldier, a bon vivant and a gentleman who lived this Second World War story.

Authors note

For more than thirty years Ive struggled with Tolek Naftali (Ted) Klings extraordinary Second World War memoir, wanting to convey it with the honesty and vividness with which it was told to me, yet drawing all the threads together to make a coherent narrative.

I still get shivers when recalling the first time I sat down with Tolek my father-in-law to record his story. After hearing many fascinating snippets of his life as a Second World War soldier, I suggested that we try and put it into a book.

Tolek bought a small, foot-operated mini tape recorder, typed up his notes on a portable Remington typewriter (similar to the one he uses in The Miracle Typist) and then, sitting at the kitchen table, he read them out into the silent, spinning reels.

I could see from the first minute that Tolek was uncomfortable with this process. It was too impersonal; too removed his face never changed expression as he read.

During the 1980s we persevered, making nine tapes before I dropped the procedure and switched to simply talking with him about his extraordinary life. Tolek was so much more comfortable with this, and I made heaps of notes during the twenty-five years we spent together, both at work and within the family.

He told his story to me feverishly, in episodes that were seldom chronological. Lunchtime in the factory, he would extract from his pockets notes and original documents that he had kept for over forty years. Tolek was a hoarder; he kept everything. He would read to me from notes jotted down the night before or even that morning in his office, continuing long after the lunchtime siren sounded. Many nights we stayed back in the brightly lit showroom after everyone had gone, sipping whisky. It was quiet and cozy, yet the brilliant lights seemed to highlight his memory flashes. It was almost as if we were isolated from the outside world in some wartime bunker.

To better understand the way Tolek Klings relayed his story to me you need to channel one of those old-fashioned flashbulb cameras.

Sudden recollections surfaced, such as FLASH the confrontation with the French high-brass in Lebanon FLASH his political, academic, philosophical exchanges with Jan the war correspondent while on army manoeuvres FLASH the time they fraternised with the Germans and Italians when the desert flooded and of course FLASH his miraculous battlefield escapes, described so vividly: hed jump to his feet, waving his arms as he re-enacted the moments over and over sometimes it felt like watching a video.

Tolek would smoke, laugh and hoot, recounting his Armageddon deliverances. But when he showed me the moment he received a miraculous telegram from his wife, Klara, whose fate he hadnt known, my heart went out to him.

And yet I was to discover that most of his story had been sanitised for my consumption. It took Tolek many years to bring himself to tell me about his time with the Modena Speakers, and even longer to relay his traumatic experience in the freezing forest after he was robbed. These episodes didnt need flashbulb moments or re-enactment. There was no smoking, hooting and laughing. He could barely look at me when relaying those events.

One night, sitting in the quiet showroom, Tolek told me about the incident in the woods at the start of the war. He hadnt even told his wife and daughter. It happened in September 1939 and in 1944, near the end of the war, he told it to the Correspondent in a ruined farmhouse in Italy. Then he told it to his brother, Ijio, when walking arm in arm through the galleria in Milan after the war. Finally, he told it to me forty years later. First, he scanned my face intently, then I could see hed made a decision. Tell it to Leon now!

What I remember as clear as daylight today thirty years later is Tolek standing up to tell me the story, and I could see so clearly that when he finished, his eyes became lighter. He no longer carried that weight it was now firmly weighing down my shoulders. He was finally vindicated; hed passed the baton on to me.

Tolek told me one day that the Second World War was above all a war of moral issues, and certainly The Miracle Typist has a much broader landscape than mere wartime memoir. Toleks story raises confronting human rights issues; it puts the war on a personal level for both the narrator and the readers. It was Toleks fervent hope that telling his story would do some long-term good, helping people of all backgrounds to understand and relate to each other as equals.

Tolek told me once: Its as if Im surrounded by doors [memories] that draw me and repulse me at the same time.

When I wrote the first rough drafts, Tolek would get very emotional when reading them. Down on paper it was official; real. Hed look up at me and nod slowly. This story needs to be told, hed whisper to himself.

This story stayed with me for about thirty years until, through the courtesy of Selwa Anthony my miracle agent and the talented Simon & Schuster team, I was able to ease it off my shoulders and share it with the rest of the world.

Tolek Klings passed away in 1996 at the age of eighty-five. We still miss him.

I raise a glass of whisky in cheers to you, Tolek: Mazldik nshmh. Lucky soul!

Leon Silver

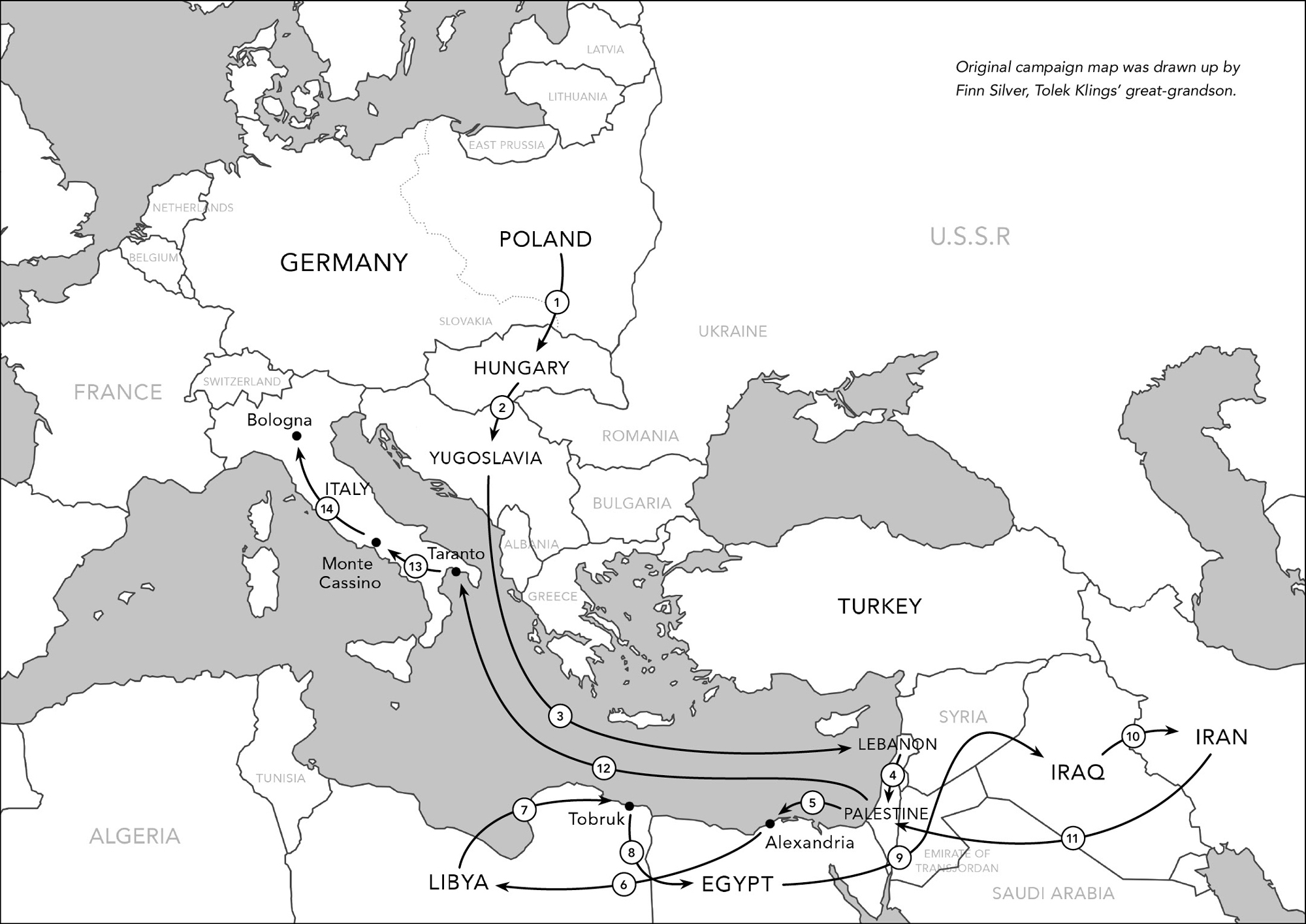

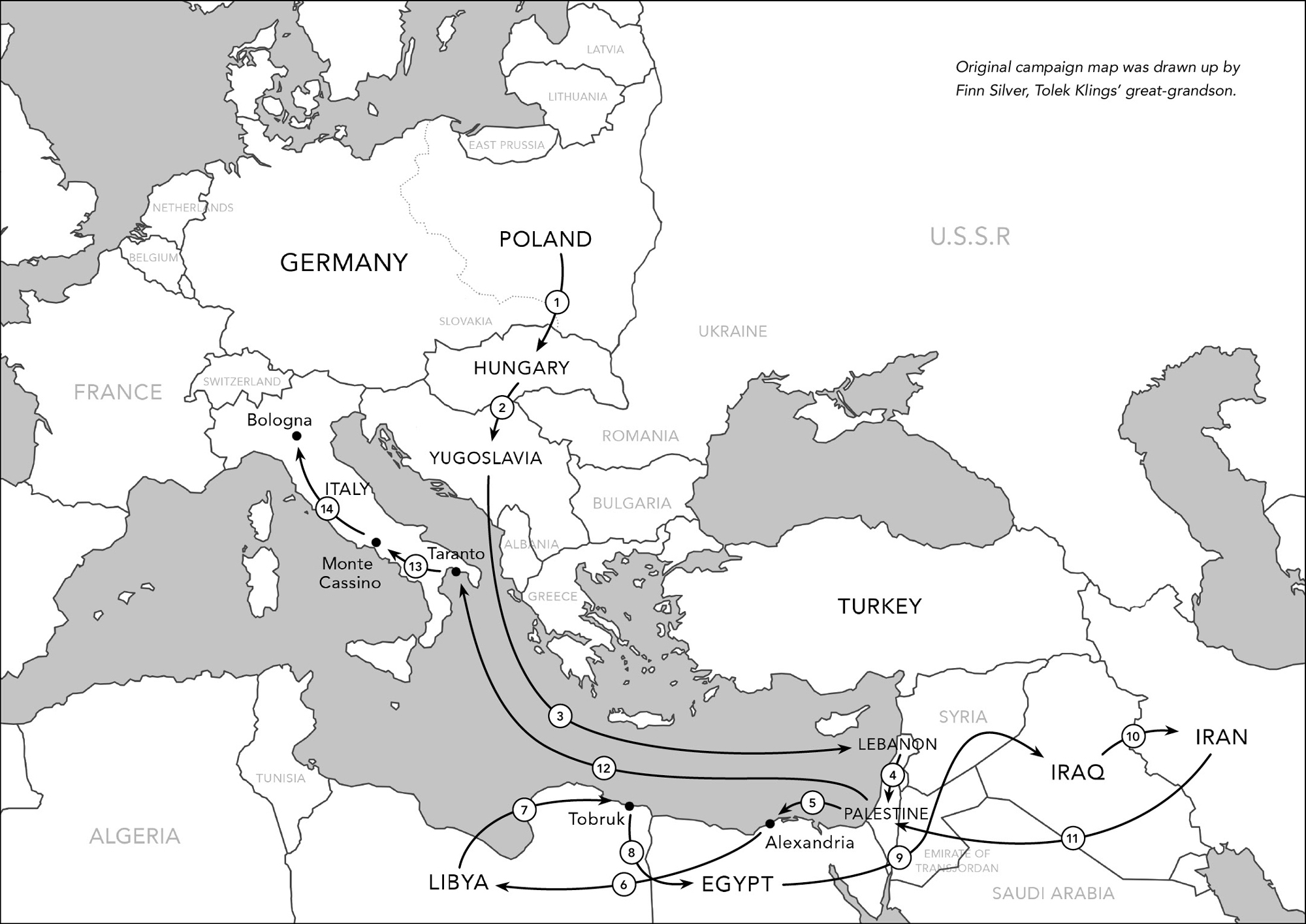

Tolek Klings movements during the Second World War.

Prologue

Bbrki, Poland

5 March 1935

Standing under a chuppah decorated with early spring flowers, Tolek Naftali Klings sucks in his breath as his bride Klara is led into the room. Tolek grins to himself. The first time he saw Klara he knew she was the one. She is wearing a long white wedding dress, the lengthy veil covering her face. Earlier that morning, in a room at the back of the wedding hall, Tolek had drawn the veil over her face in the traditional bedeken the covering of the bride ceremony, a symbol that soul and character surpass physical beauty. Klara had crinkled her nose and smiled at her groom, an even more essential part of their private ceremony.

Now, Klara enters the packed room with her mother, Jutta, her sisters Henie and Sime, and Toleks mother, Lieba. Klara is all excited smiles and Tolek knows it amuses her that shes moving from a family of five women and one man to a family of four men and one woman. Joel, Klaras father, died of a heart attack a few months earlier. Tolek will make sure that his daughter is fully embraced by her new family.

Beaming, Klara transmits her love to him through the thin gauze veil. Black eyes, exquisitely made up, tender and yearning for him. Soon we will be one, she whispers.

Tolek hums the Russian love song he used to sing to Klara while they were courting. i jrnye Dark Eyes written by Ukrainian poet Yevhen Hrebinka in the mid-nineteenth century.

Black eyes, passionate eyes,

Burning and beautiful eyes!

Rabbi Zvi exchanges looks with Tolek then nods to start proceedings. Blessed are thou, oh Lord, King of the Universe, who created mirth and joy, bridegroom and bride, gladness, jubilation, dancing, and delight, love and brotherhood, peace and fellowship