NormandySainte Mre glise. Courtesy of Brannon Judd and Pritchett Cotten

NormandyLa Fire Causeway. Courtesy of Brannon Judd and Pritchett Cotten

Foreword

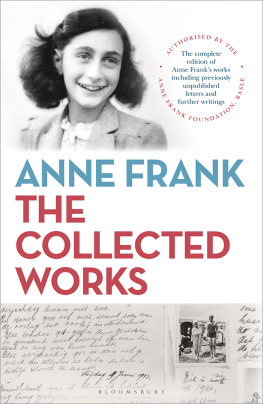

W hen I was growing up in rural North Carolina during the 1970s and 80s, I customarily met veterans from both World War II and Korea. Many veterans were reluctant to discuss their war experiences. I considered myself lucky when they felt comfortable enough to talk about it. I learned to be patient, especially with an uncle who was a decorated World War II veteran who served with the U.S. 1st Armored Division in both the African and Italian Campaigns. He survived the Battle of Anzio but was severely injured during a fight against German Tiger tanks. He drove a tank that was destroyed by a Mark VI Tiger. He was knocked unconscious but awakened to the sight of all his combat crew members dead and body parts scattered everywhere. The war affected him all his life, and sadly, I helped bury him in western North Carolina, Christmas of 2018. One of my cousins served in the Navy as a sailor aboard the USS Pennsylvania during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Thankfully, he managed to document his story with a video interview following a family reunion. Most of the stories I heard from veterans centered upon theaters of action, weapons, and the units they served under. Early in my career, I became a veteran after volunteering for the U.S. Army during the 1980s. While serving as a U.S. Army field artillery surveyor, I witnessed the Cold War and the Soviet Unions attempt to force communism upon Western Europe. I walked some of the battlefields of both world wars and became a scholar of U.S. military history. It didnt take long to understand that freedom is never cheap. Plus I knew that the veterans of World War II were exceptional and deserved special examination.

Based on my military experience, several years of historic reenacting, and collegiate work in public history, I developed a unique perspective on military historiography. I felt tasked to write a book that could be used by students and novice historians to better define and understand the soldiers of the Greatest Generation. Central questions I wanted to answer included: What made the American soldier of World War II one of the most resourceful and productive soldiers in world history? Furthermore, how can I memorialize veterans who lived during the worldwide depression? The U.S. military was underfunded, lacked resources, and was vastly undermanned. So how, when given the task to defend freedom, did some of these veterans choose service before finishing high school? The forces that aligned against them in 1941 were dark and overwhelming.

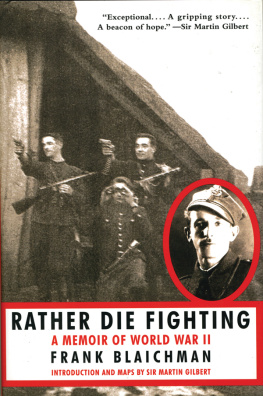

I hope the readers of Harold Franks story understand that a weapon is no better than the soldier whom it equips. Contrast that with the survivability of a combat veteran. Survivability was due to a combination of military training, childhood upbringing, environmental factors, and faith in God. Adaptability to change, whether environmental or physical, is difficult to train in most military recruits. Living through the Great Depression produced a generation of Americans used to rugged conditions at home. They had to find adaptive and innovative ways to survive in an environment filled with unemployment, low wages, consumer debt, agricultural struggles due to drought, dropping food prices, and banks unable to liquidate loans. In spite of these hard times it became necessary to prepare for Americas entry into World War II. Volunteers were recruited to join our military. We also needed a workforce capable of producing munitions, armaments, and other supplies. Factories and industrial resources in shipbuilding, aircraft, cars, and tanks contributed substantially to the war effort. So did the Americans who built them. Overall, American ingenuity burst forth from the generation of people who lived in the Great Depression. This diversity and what it meant to step up in our countrys time of need was embedded in our veterans of World War II. The world recognized such soldiers as a type: the American combat soldier.

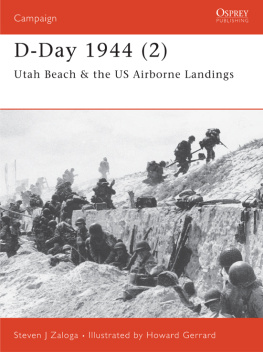

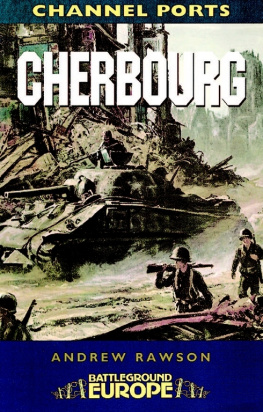

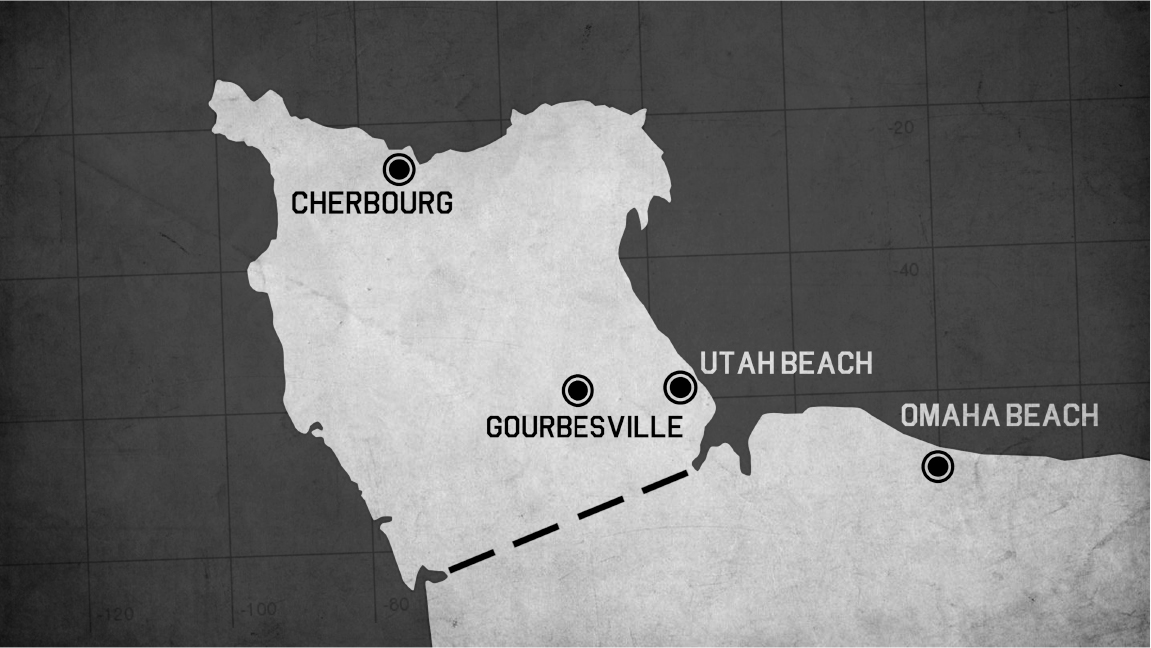

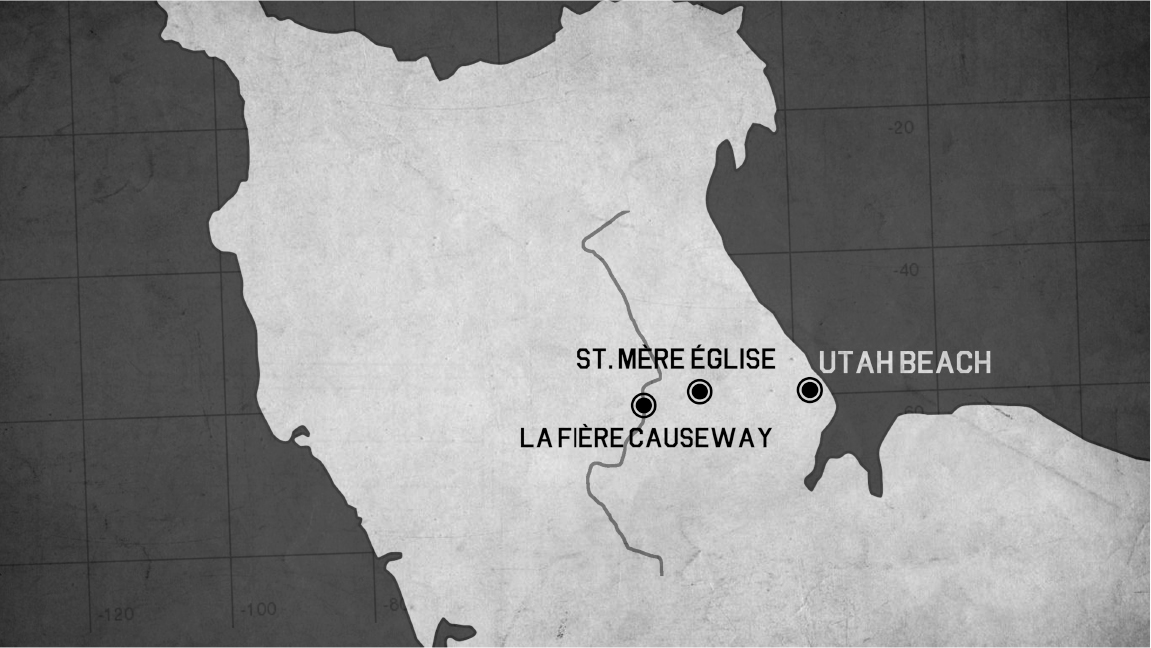

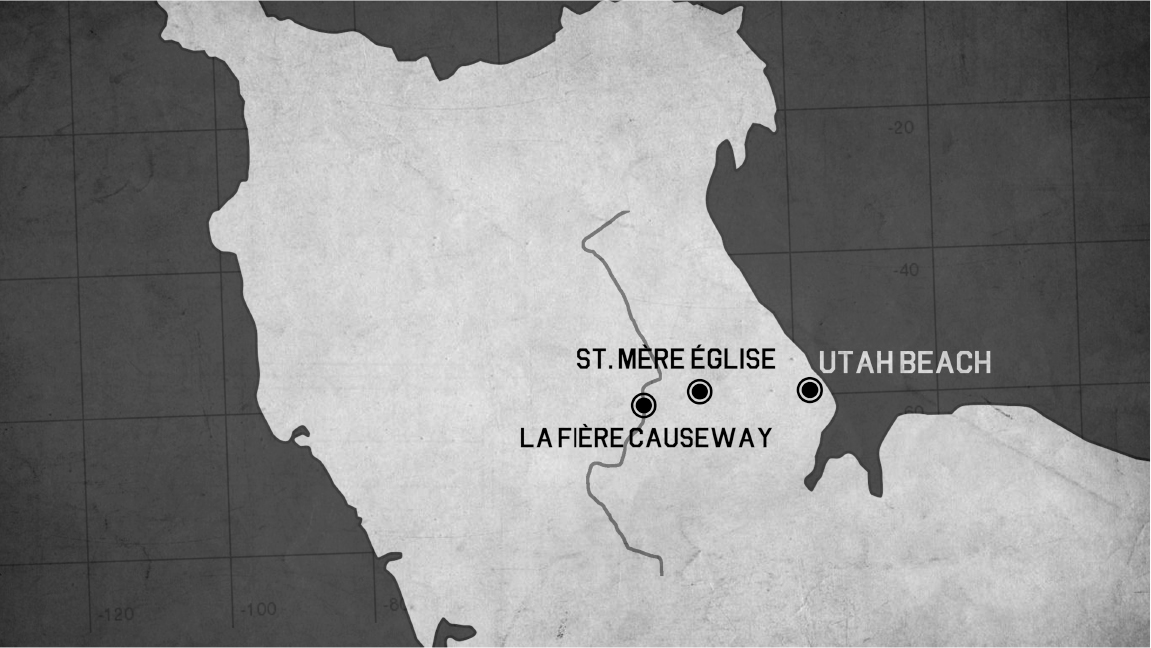

Presenting the story of Harold Frank became a real challenge requiring a more expansive approach to historiography. Years of university studies, research, and work in public history were beneficial for investigating military experience in a way that I call ground truthing. In other words, will the reader be equipped to understand the struggle a veteran endures in combat? Also, Harold Franks story draws an additional element of what it was like to be a POW in Nazi Germany. The treatment of U.S. POWs by both German and Japanese forces is well documented. Atrocities were numerous, with starvation and executions a stark commonalty. While interviewing Harold Frank in the discovery phase, all battles, weapons, and units were investigated through sources ranging from Normandy, France; Fort Bragg, North Carolina; the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force, Savannah, Georgia; the National D-Day Museum (now the National WWII Museum) in New Orleans; and various secondary written sources. The process clearly revealed that the survival of Harold Frank bordered more on miraculous than just extraordinary circumstances. Case in point was the collision course that Allied soldiers faced after D-Day on the Cotentin Peninsula of France.

The Cotentin Peninsula and its important port at Cherbourg became a matter of importance to hold at all costs for both German and Allied forces. The 357th Infantry was given the audacious task of blocking movements of the German Army either retreating from or attempting to reinforce Cherbourg. The result was an intense struggle in daily combat without reprieve for several months, ending in the battles of Gourbesville, Hill 122, Beaucoudray, and Saint-L. The regiment suffered horrendous losses and multiple companies were virtually destroyed. Harold Frank served in the U.S. 2nd Battalion, Company G of the 357th Infantry which landed on Utah Beach, June 8, 1944 (D-Day+2). His battalion met heavy resistance as they attempted to relieve isolated pockets of the 101st and 82nd Airborne units operating in and around the Merderet River Bridge. A month later Harold Frank, being the last experienced BAR rifleman in the 357th, led a night patrol to find two lost U.S. infantry companies. Simultaneously the 15th German Parachute Regiment launched a massive counterattack catching the exposed patrol. Although wounded, Harold Frank and four others fought for nine hours and diverted enough attention to blunt the German offensive. Harold Frank survived but was captured. He endured and survived a ten-month POW experience that many of his compatriots succumbed to.