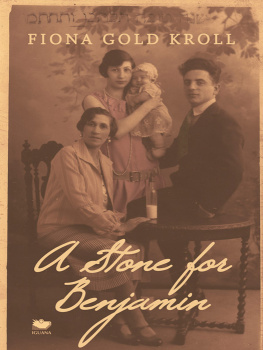

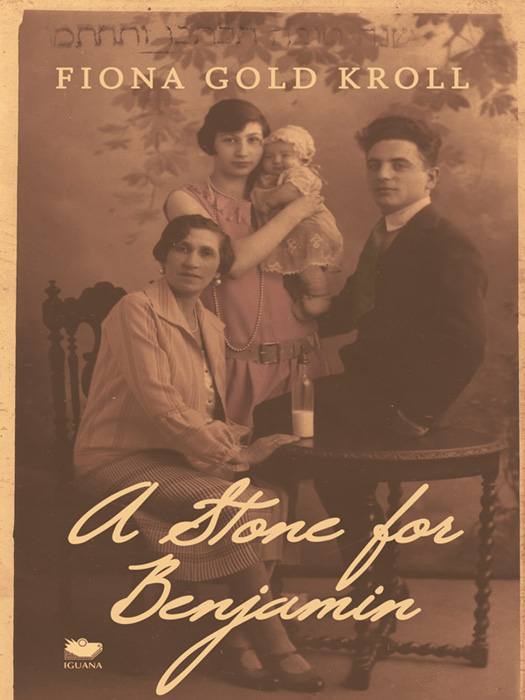

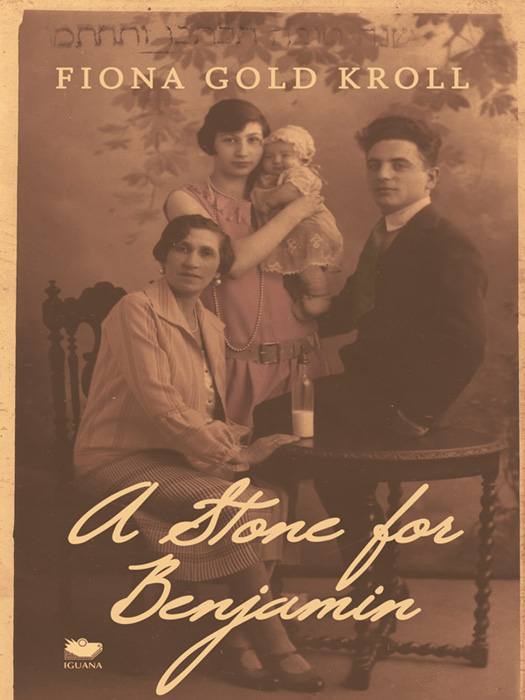

Copyright 2013 Fiona Gold Kroll

Published by Iguana Books

720 Bathurst Street, Suite 303

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5V 2R4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise (except brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of the author or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Publisher: Greg Ioannou

Editors: Marie-Lynn Hammond, Kate Unrau

Front cover design: Jane Awde Goodwin

Book layout design: Meghan Behse

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication to come.

Kroll, Fiona Gold, 1948-, author

A stone for Benjamin / Fiona Gold Kroll.

Issued also in electronic format.

ISBN 978-1-77180-007-5 (pbk.). ISBN 978-1-77180-009-9 (Kindle).

ISBN 978-1-77180-008-2 (pdf). ISBN 978-1-77180-010-5 (epub)

1. Albaum, Benjamin, 1905-1943. 2. Soldiers France Biography.

3. Jews France Paris Biography. 4. Auschwitz (Concentration camp) Biography. 5. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) France. 6. World War,

1939-1945 Deportations from France. I. Title.

| DS135.F9A53 2013 | 940.5318092 | C2013-907067-2 |

| C2013-907068-0 |

This is an original electronic edition of A Stone for Benjamin.

For Bob

In memory of Carole and Bernard, my parents

the most bestial, the most squalid and the most senseless of all their offences, namely, the mass deportation of Jews from France, with the pitiful horrors attendant upon the calculated and final scattering of families. This tragedy fills me with astonishment as well as with indignation, and it illustrates as nothing else can the utter degradation of the Nazi nature and theme, and degradation of all who lend themselves to its unnatural and perverted passions.

Winston S. Churchill The House of Commons, September 1942

INTRODUCTION

My father is dying. He has slipped into a coma, and I hold his hand as he rests peacefully in his bed. He is in a private room in the hospice on the ground floor of a hospital near Toronto. Two Canada geese stand like sentries outside the window, and the sun shines brightly into the room with a promise of spring and life, exactly as he would have wanted it.

Orphaned by the age of ten, my father faced life with enthusiasm in spite of his loss. Whenever challenges presented themselves, he would get back up on his feet, choose to see the glass half full and move on. My parents remained married for almost sixty-five mostly-happy years, until my mother died ten months earlier. Following her death, my fathers rapidly failing health came as no surprise.

I had an exceptional relationship with my father. If he refused to do something my mother wanted, she would say to me, You speak to Dad. Hell listen to you. His love and encouragement remained unconditional throughout my life. When I began searching for my great-uncle Benjamin, who disappeared in 1941, my father became my biggest supporter and sounding board. Although Benjamin was my mothers uncle, my parents viewed both sides of the family as one. For my father, Benjamin was also his uncle end of story.

Sitting beside my father a few days before he slipped into the coma, I held his frail hand in mine. His voice was weak as we discussed my search for Benjamin.

He turned his head towards me and said, You have to write this book.

CHAPTER 1

I ran into her bedroom every morning, waiting patiently for Sheva to hand me a biscuit from the packet she kept tucked away in the night table beside her bed. We lived with my grandparents. My grandmother was a powerhouse, in personality if not in stature she stood four feet, ten inches tall. I was too young to understand, and I didnt realize that Sheva was ill; she passed away when I was barely two years old. Despite my age at the time, I still remember some incidents that occurred back then, and my grandmothers face is etched in my memory. My grandfathers, too.

My mother and I visited my grandfather each week at his factory in the East End of London. Scooping me into his arms as soon as he saw me, my grandfather called me mamela (little mother in Yiddish). Sometimes I climbed on his lap while he brought his big, gentle hands around in front of me. He would carefully peel, core and slice an apple, and we would share it. Then he would take my small hand, covering it with his large, calloused fingers as we walked across the street together to Mr. Roumanias shop.

Standing on my toes, I would crane my neck in an effort to see the contents of the huge, clear glass jars of sweets lined up like soldiers on the shelves behind the counter. My grandfather waited patiently while I chose a mixture to take home with me. Mr. Roumania weighed the sweets and carefully poured them into a small, white paper bag. He held the two corners of the bag together then quickly tossed the bag over several times to create twists at each end ensuring the bag stayed closed. My grandfather paid him, but he accepted the money under protest Mr. Roumania had known my grandfather since before the war.

My grandfather did not enjoy living alone and he remarried one year after Sheva died. He adored his grandchildren, and I loved watching him smile when I walked into a room. I always looked up to him; he made me feel safe. He died when I was eight. I wish I had known him longer.

My grandparents carried passports that identified them as Russian Poles, though they were Polish Jews who immigrated to London, England, where my parents, my brother and I were born. My family never discussed the Holocaust during my childhood, and the Hebrew school that I attended didnt teach the subject either. Though I knew that something terrible had happened to my grandparents families during the war, I sensed that I was never to ask my mother about it. My father and I shared a common interest in history. An avid reader, my father had several books pertaining to World War II, though none of them were specifically about the Holocaust, a subject we never discussed in front of my mother.

My mother never read a book or saw a movie concerning the Holocaust, and whenever a documentary about the subject came on television, my father would quickly change the channel so as not to upset my mother. Privately I sought out documentaries and movies about the Holocaust and read as many books as I could find on the topic, though never at home.

The Jewish calendar contains many joyful celebrations, but as a young child I could never adjust to the sombre mood of Yom Kippur. The Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur is the time when Jews ask forgiveness for their sins of the previous year, and we remember all those people who are no longer with us.

The night before Yom Kippur, Jews light a remembrance candle at sunset in memory of the dead. The candle burns for at least twenty-four hours. We not only remember dead family members but also victims murdered during the Holocaust. All four of my grandparents were dead by the time I reached the age of eight, and my parents mourned the loss of their own parents along with the loss of several of their siblings. My mother usually ushered me out of the synagogue before prayers for those lost in the Holocaust began; I like to think that my parents tried to protect my childhood innocence for as long as possible. Fasting began at sunset the night before Yom Kippur. By the following morning, my mother always ended up with a full-blown migraine, but my parents went to synagogue and continued fasting for the entire day until one hour after the sunset. I couldnt understand why my mother would do something that made her so ill and so sad. I did not understand the significance of the day or of our prayers for the dead until I reached adulthood.

Next page