CONTENTS

Guide

Mary Grace Flaherty is an associate professor in the School of Information and Library Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She received her PhD from Syracuse University, where she was an IMLS Fellow. Mary Grace has her MLS from the University of Maryland and an MS in Applied Behavioral Science from Johns Hopkins University. Before turning to teaching and engaging with the next generation of librarians, Mary Grace worked in a variety of library settings, including academic, health research, public, and special.

M y sincerest thanks to all the librarians out there who are making their communities stronger, more versatile, and more welcoming places. My gratitude to Charles Harmon, who buoyed me along, and to Erinn Slanina for her helpful support. I would also like to thank GW for their unfailing support throughout the process. Sincere thanks as well to all the contributorsSuzanne Bloom, Vickery Bowles, Erica Brody, Amelia Gibson, Taylor Johnson, Leila Ledbetter, Noah Lenstra, Maggie Melo, David Miller, Lydia Neuroth, and Gwendolyn Reecefor sharing their stories.

A s part of their educational mission, libraries have long been in the business of hosting events and programs. In fact, programs can be viewed as yet another resource or opportunity that libraries have regularly offered to their communities. Public libraries have been codifying and reporting on such initiatives for some time now. The first issues of the New York Public Librarys (NYPL) monthly print publication, Branch Library News, from more than a century ago describe a variety of book clubs, exhibits, and meetings that were supported through the librarys routine program opportunities (New York Public Library, 1914ad). Some of the offerings bear some similarity to programs offered by public, academic, and special libraries today.

Examples include:

- Library, literary, and reading clubs

- Debates (the first was When the Boys Literary Club of the 115th Street Branch challenged the boys of the Harlem Library League to a trial debate, 1914a, p. 96)

- Illustrated talks on the districts history

- Job talks by school principals for new graduates (separate talks were given to boys and girls)

- Guest speakers, such as authors and a local judge

- Musical programs

- Mothers clubs

- Exhibits with topics such as child welfare (including books, maps, photographs); Indians in the Southwest (with pottery, baskets, photographs); and a 350th anniversary celebration of Shakespeares birth (with rare prints and editions on display)

- English classes

- Neighborhood and civic organization meetings

Even in 1914, the importance of the libraries connection to community was emphasized. They were considered akin to schools in the movement to make schoolhouses as civic and social centres [sic] of the community, as they were similarly described to naturally offer striking opportunities for neighborhood development (NYPL, 1914e). Along these lines, the branch libraries were depicted as integral meeting-places (NYPL, 1914f). The 1913 annual report describes the frequent and varied use of the branch library as the logical meeting-place for clubs and organizations that represent the life of the community, and the monthly bulletin reports that two organizations of physicians held their first meetings in February (NYPL, 1914g). So, along with their resource and information provision roles, libraries have for more than a century been understood by the public to be places for hosting events and providing community meeting opportunities. Many programs, like childrens story time, may not ever be attended by most people, and yet those same people will be vehement supporters of those services. Program events help define the communitys values and the librarys mission, and bring those two entities closer together. Library events can be bigger than the events themselves.

STARTING THE BALL ROLLING

Defining the Mission, Purpose, and Scope of the Event

As with many endeavors, the first step in event planning is to define the mission and purpose. What is the mission of the event and how does it fit in with the larger library mission? Is the event part of an initiative to promote literacy or lifelong learning? Is it to highlight or promote library resources? Is its purpose to respond to current community challenges? As for scope, will it be targeted to a specific user group, or is the purpose to bring in or reach out to new library users? Will it include other communities or regional and statewide partners? The mission and purpose will then steer the choice of topic and guide decisions about whether this will be a short- or long-term project and whether it will be a one-shot event or ongoing offering (as will the ultimate results of the event). For example, if there is little community interest in the first trial of a program, it may not be worth repeating.

Some purposes are readily defined because of their unique circumstance, such as in the case of special events (e.g., anniversary celebrations) and established programs (e.g., summer reading in public libraries).

The following questions can help to frame the process during the idea formation phase:

- Who is the likely audience?

- What are your goals and objectives?

- Who (if anyone) are likely collaborators?

- When will the event take place, and what are the milestones in between?

- How will you ensure accessibility and inclusivity?

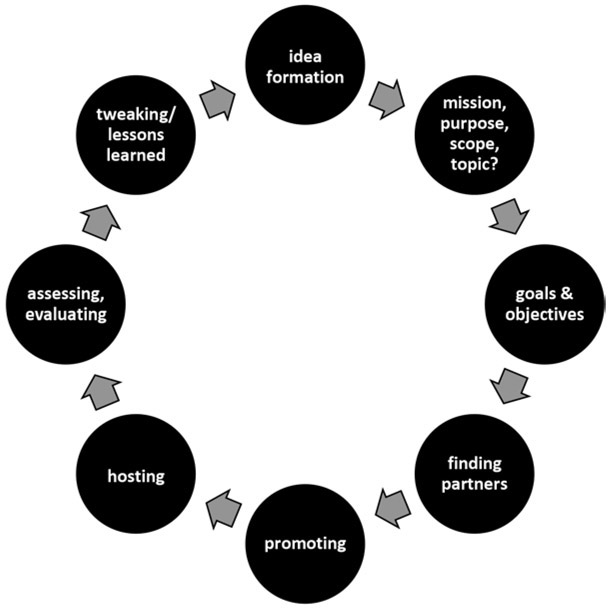

Figure 1.1. Stages of library programs. Courtesy of the author

CHOOSING THE TOPIC

Determining Your Audience

The purpose of the program or event will likely determine both the target audience and the specific topic. For instance, if as director of an academic library you have a newly formed collaboration with your student health center, programs might be steered toward issues that are affecting a segment of the student population, such as stress reduction for incoming first-years.

As with collection development and other library activities, responding to community needs and wishes is paramount in terms of library service provision. This dependence on community interest is not only because of attendance; it also influences long-term financial support for the library and staff morale and enthusiasm. But who determines what those community needs are? How are those needs codified? And how are communities wishes made known?

The Network of the National Library of Medicine (NNLM) describes community engagement as a continuum. At one end are activities that simply make the community aware of services, while at the other end, patrons have leadership responsibilities within the organization.

The NNLM provides a free community engagement toolkit (available at https://nnlm.gov/all-of-us/cp/resource/community-engagement-toolkit) that helps to build upon the already established and direct knowledge of patrons that occurs through regular interaction. The NNLM advocates for using community assessments to better know your audience as a way to ensure programs and services are relevant to the needs, strengths, and interests of the community. Assessments can also help to identify any gaps in services or community members that are not being regularly reached. The community engagement toolkit provides links to free, readily available resources, such as a Community Assessment Factsheet and a Community Tool Box.

There are also resources for utilizing health statistics in community assessments, such as the County Health Rankings (https://www.countyhealthrankings.org) available from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Using such tools can help to determine what topics current programs and events might cover. For instance, by examining health rankings, you may discover the community has a high rate of a particular health concern and can adapt programming to offer support to address that concern. Once the topic and audience have been determined, its time to turn to goals and objectives.