Copyright 2015 Smithsonian Institution.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This eBook may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write:

Special Markets Department

Smithsonian Books

PO Box 37012

MRC 513

Washington, DC, 20013.

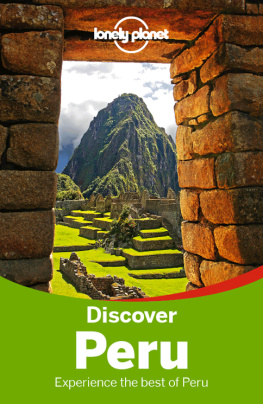

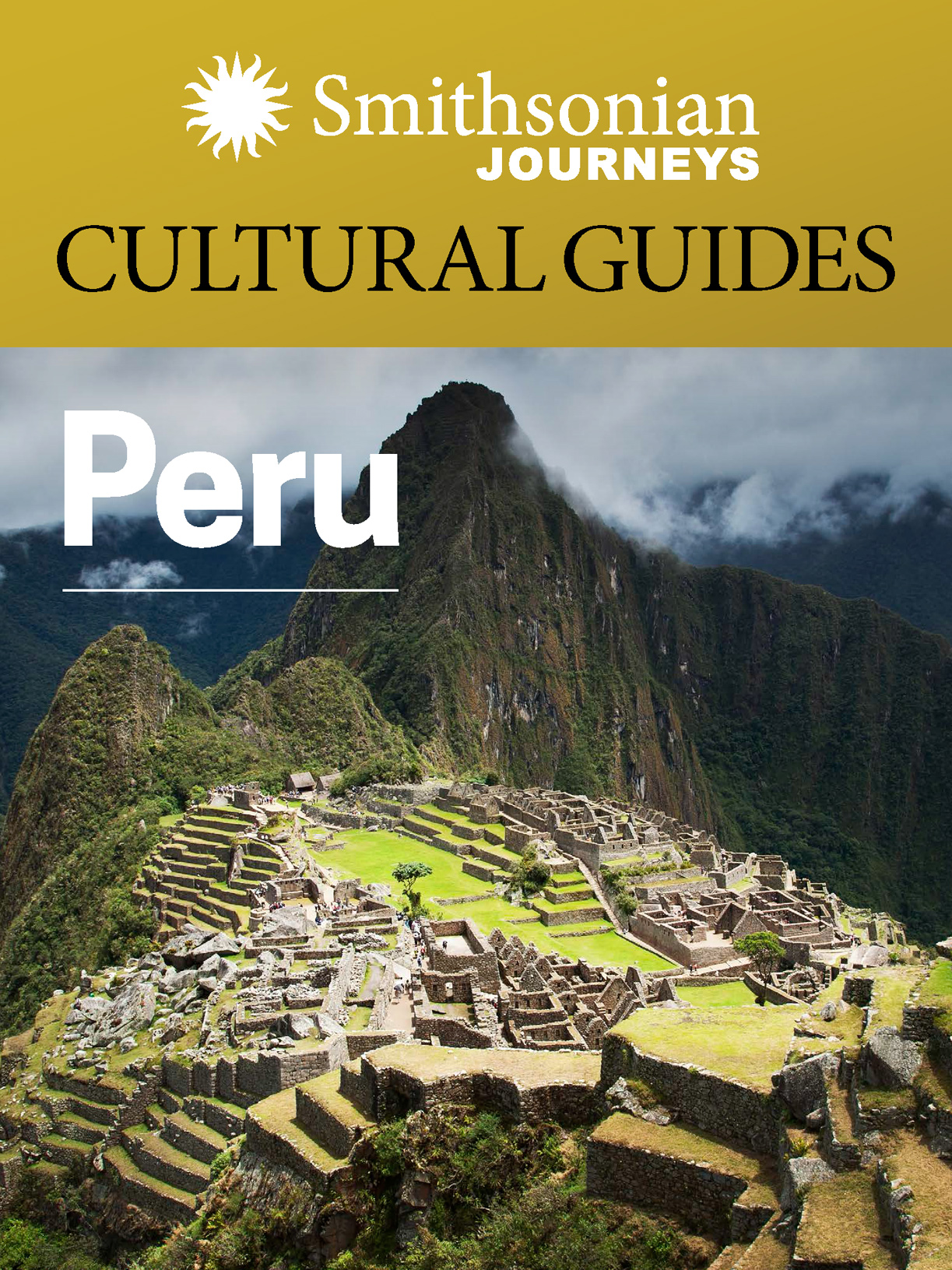

Inca doorway, Machu Picchu

Peru has a remarkable array of habitats and ecosystems. Of the 117 life zones found on our planet, 84 exist somewhere within the boundaries of modern Peru. Whether along the Pacific shore, in the High Andes, or deep in the Amazon rainforest, this natural diversity enabled humans to flourish along the west side of South America, spawning a series of advanced civilizations that culminated in the Incas.

Although none of these societies developed any form of writing that has yet been detected, they were highly sophisticated in many other ways. Their cities were among the most impressive of the ancient world. Cuzco, Chan Chan, Tcume, and Machu Picchu endure as proof that ancient civilization in the western hemisphere attained and sometimes surpassed the feats of those in the east. The practice of mummification among Perus ancient peoples has added greatly to our understanding of their cultures and lifestyles. Mostly uncovered high in the Andes, where the dry air, thin atmosphere, and cold temperatures have helped preserve the bodies, mummies are regularly found by explorers. The celebrated Momia Juanitathe Inca ice maidenwas discovered in 1995 by National Geographic explorer-in-residence Johan Reinhard and his Peruvian guide Miguel Zrate on Perus Mount Ampato. An autopsy showed that Juanita was killed by a blunt trauma to the head, suggesting she was a victim of human sacrifice. Inca kings and leaders were also mummified, though none of their remains have been found. Pre-Inca cultures also preserved their dead. The mummy of a heavily tattooed woman thought to have been a warrior queen was excavated in 2006 at a ceremonial site called El Brujo (The Sorcerer) on the north coast of Peru. Seora de Cao, as she was named, has helped expand our knowledge of the ancient Moche culture, which preceded the Incas. Chauchilla Cemetery near Nazca has also yielded a trove of mummies, some dating back 1,000 years.

The land bridge theory

Archaeological evidence shows that the first humans settled in Peru around 13,000 years ago, with the earliest traces along the coast south of the capital Lima. No consensus has emerged on how they migrated into the region. Historical convention has long held that all of the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere arrived from Asia via Beringia, a land bridge during the last Ice Age that connected what are now Alaska and eastern Russia. However, newer theories propose that humans from Polynesia and Asia may have also arrived on long-distance voyages across the Pacific.

While their exact origin is a mystery, the earliest Peruvians left physical evidence of their habits and lifestyles. Small settlements of fewer than 100 people living in extended family groups developed along the coast near river mouths. These people survived mostly by harvesting the ocean, though some migrated to higher ground seasonally to hunt animals and gather plants. Quebrada Tacahuay, near modern-day Tacna, inhabited from around 10,700 BC, was typical of these early settlements. Its residents lived on the coast most of the time, netting and trapping small fish, collecting shellfish, and hunting seabirds, but they migrated into the highlands for part of the year.

Agricultural societies

The ancient Peruvians eventually evolved from hunter-gatherers into agriculturalists. Evidence shows they domesticated llamas as a source of meat and wool around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, while guinea pigs first appeared as a food source in households around 5000 BC. The origins of farming can likewise be dated to about 5000 BC, with the cultivation of potatoes, beans, and peanuts followed soon after by cotton.

The development of agriculture led to the emergence of more advanced civilizations by 3000 BCaround the same time as the flowering of other proto-cultures in China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley. Although much of the Peruvian coast is desert, agriculture was possible around the river valleys with the help of irrigation. Creating, maintaining, and defending large-scale irrigation systems required the organized labor of many people. As a result, Perus earliest urban centers emerged in coastal river valleys.

The oldest city in the Americas

The remains of a vast ancient city called Caral, dating from about 2600 BC, are now under intense study. Discovered in 1905 near Trujillo on Perus north coast, the site is considered the oldest city in the Americas, its age determined by the carbon dating of reed baskets, musical instruments, clothing, and animal remains. The settlement featured residential areas and pyramids reaching 40 feet in height. Archaeologists surmise that seafood, peanuts, and beans formed a large part of the diet of the inhabitants, who cooked over hot rocks in this pre-ceramic society, grew and wove cotton for clothing, and played bone flutes to provide music at events held in a central amphitheater. The people traded as far as the Andes and Amazon.

Amphitheater at Caral

Chavn culture

The Chavn were Perus earliest identifiable widespread people. Emerging as early as 1000 BC and flourishing between 300 and 200 BC, they populated Perus central coast until their decline around 200 BC. They cultivated corn and potatoes on farmland irrigated by a system of dams and aqueducts, which also channeled water to residential areas, developed pottery, and kept llamas and alpacas for food and wool. However, the Chavn were not a warlike people and probably had a narrowly focused political-religious hierarchy.

Chavn de Huntar, the religious and political hub of their society, was based around a temple complex in the mountains north of present-day Lima. The city boasted flat-topped pyramids, circular courtyards, and temples with stone carvings incorporating numerous animals, including the jaguar. The Chavn buried their dead with food and other goods for the afterlife. Pablo Picasso was deeply influenced by the Chavn art and design exhibited in late 19th-century Europe.

Moche culture

In 1987, Peruvian archaeologists led by Walter Alva uncovered the richest tombs ever found from the pre-Columbian Americas in an adobe pyramid in the Lambayeque Valley in northern Peru. Their attention had been drawn to the site by gold artifacts looted by tomb robbers. The aristocratic burials, all interred within the same pyramid, rivaled any of the other great burials from the ancient world, such as Tutankhamuns in Egypt.