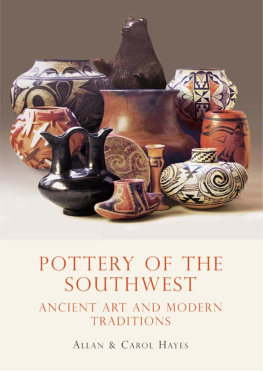

POTTERY OF THE SOUTHWEST

ANCIENT ART AND MODERN TRADITIONS

Allan & Carol Hayes

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

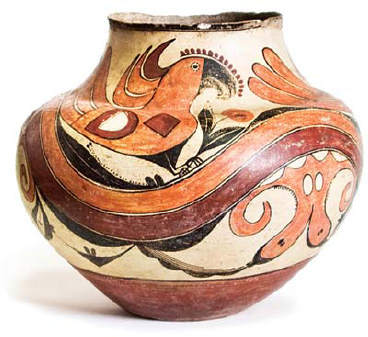

Acoma Polychrome, maker unknown, c. 1885

CONTENTS

Santa Clara, Teresita Naranjo, c. 1965

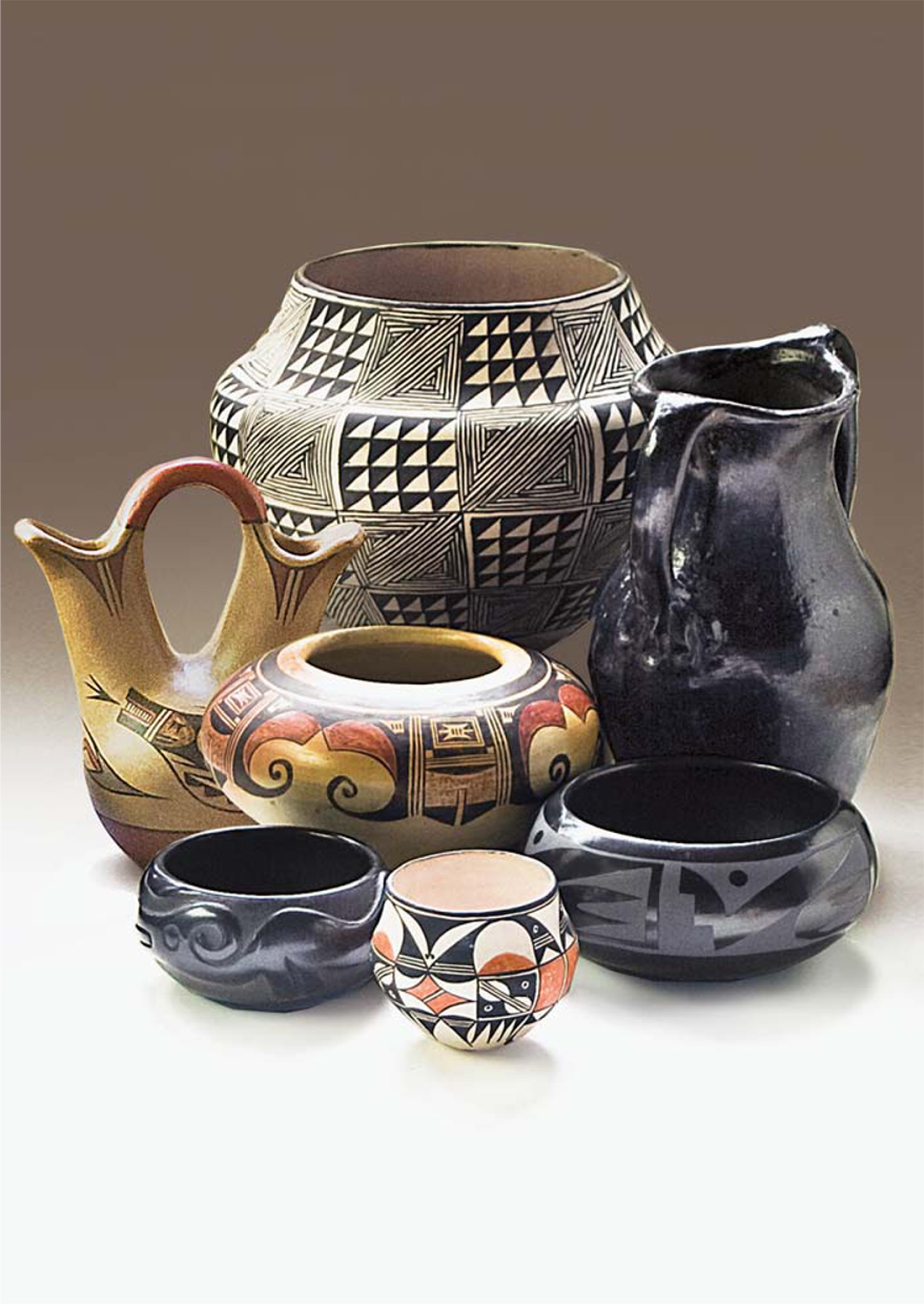

the Old Masters: In the center, Nampeyo (Hopi) jar made with her daughter Nellie, c. 1930. Clockwise from the top: Marie Chino (Acoma) jar, 1967; Sara Fina Tafoya (Santa Clara) vase, c. 1910; Maria & Julian Martinez (San Ildefonso) jar, c. 1935; Lucy Lewis (Acoma) jar, c. 1985; Rose Gonzales (San Ildefonso) jar, c. 1940; Lela & Van Gutierrez (Santa Clara) wedding vase, c. 1935. Marie Chinos 10" diameter jar won a ribbon at the 1967 Gallup Ceremonial.

THE ART

T HE POTTERY of the Indians of the Southwestern United States has been made by the same people in the same places continuously for almost two thousand years, almost always with the same materials (dirt dug up near where they live), and techniques (hand coiling, hand polishing, and pit firing). The tradition passes down from mother to daughter, and elements from a thousand years earlier reappear in todays finest pieces.

Despite all that weight of tradition, the art is at its peak, remarkably unaffected by modern life. The best potters still mix their clays, then coil, smooth, and fire their work the way potters did at the beginning. Although technology hasnt gone totally unnoticed (now some potters fire in a kiln rather than in an outdoor pit), the only real change in the art is cultural. Before the twentieth century, women made the pots and men did other work, but its now an equal-opportunity world. The prizewinning pot you buy today is just as likely to have been made by a man as by a woman.

Theres so much of this pottery that its easy to collect. Anyone can find pieces from any time period and by the most celebrated artists. Thanks to the Internet, collecting is easy anywhere in the world, and interesting pieces wont necessarily cost a lot. Most pieces in this book came from our own collecting, many bought within buying rules we set for ourselves in the 1990s: If its over $40, think hard about buying it; if its over $100, think real hard; if its over $400, dont think about it at all. Prices have gone up since then, but not all that much. You can still find good pieces within those price ranges.

This picture proves the point. It shows typical examples by the matriarchs of the seven families whose work dominated the art through the twentieth century, anointed in a 1984 exhibit as the greatest of them all: Nampeyo, Maria Martinez, Rose Gonzales, Sara Fina Tafoya, Lela Gutierrez, Lucy Lewis, and Marie Chino. Theyre the closest thing to Old Masters the art has to offer, yet we found all these pieces in 2009 and 2010 and bought them at prices not too far from those 1990s rules.

The illustrated timeline on the next six pages shows how this wildly diverse, surprisingly consistent, and incredibly accessible art form evolved.

EVOLUTION, PART I: CRUDE BEGINNINGS, THEN GROWTH

Pottery in the American Southwest began as a utilitarian craft and gradually became an important art form. Pottery didnt become widely useful in the Southwest until around 400 AD. Before then, the hunter-gatherers of Arizona and New Mexico didnt need heavy, breakable storage. Like early cultures all over the world, they concentrated on weaving and basketry.

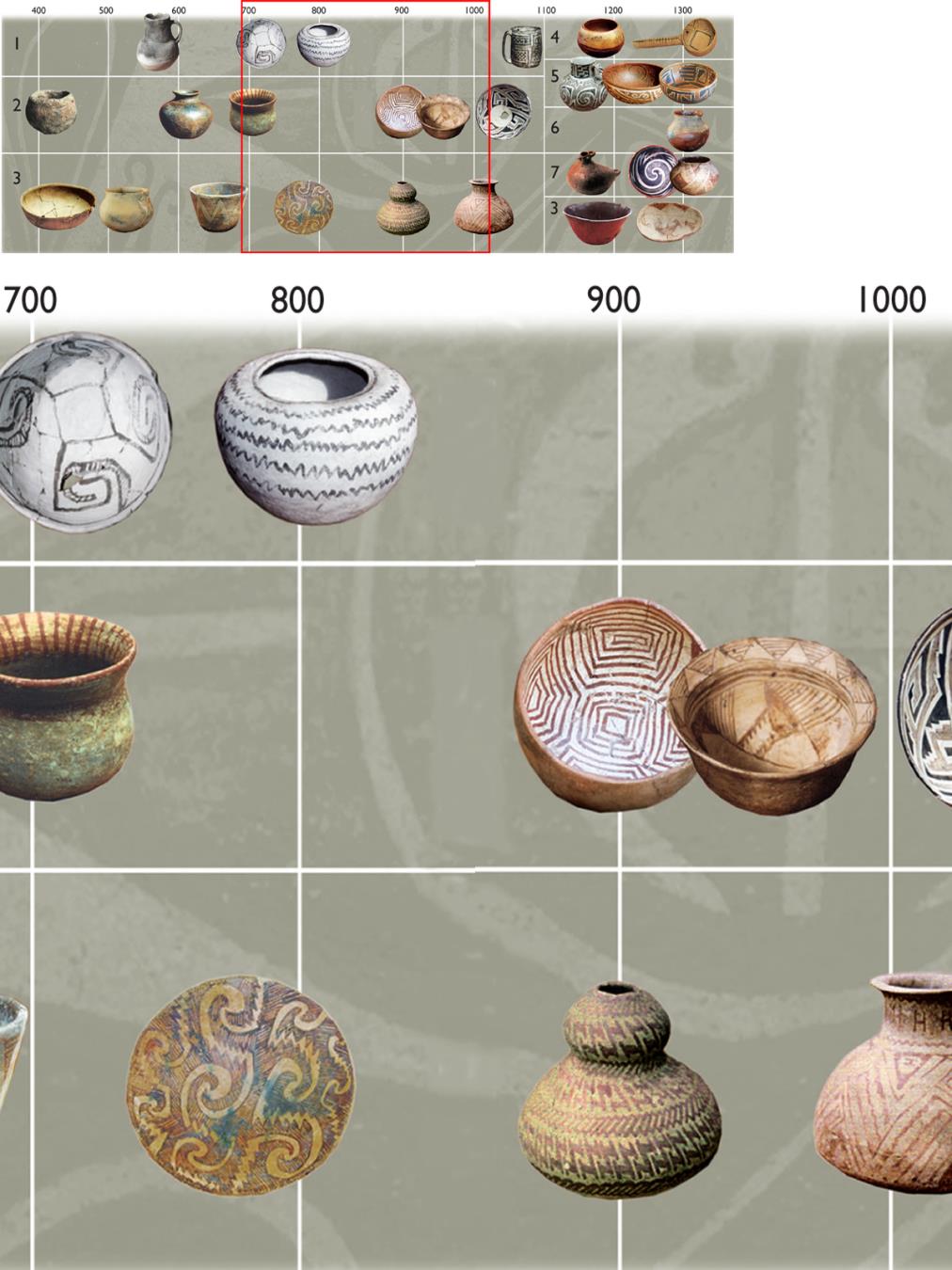

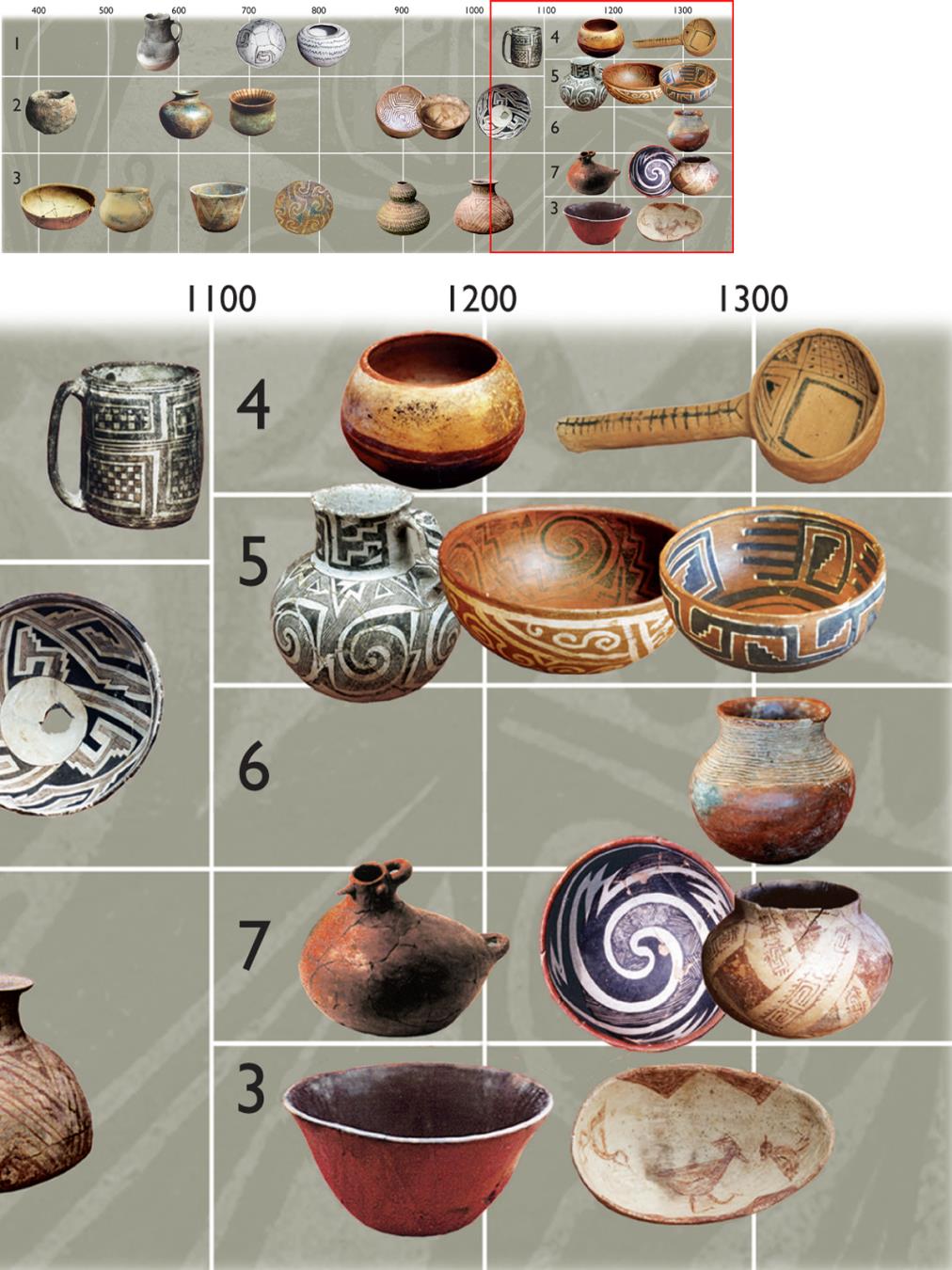

Pottery first emerged about two hundred years before, when they became serious farmers. These two pages take you from the early days of farming up to the fourteenth century. The horizontal paths follow different native groups from Arizona and New Mexico and show how they evolved their craft. Heres what happened, through the years and by the numbers:

1. ANASAZI: This is the best-known, or at least most-publicized, of the prehistoric Southwestern cultures. (The word Anasazi is rapidly being replaced by Ancestral Puebloan.) They started making grayware around 500, and by 700, added black designs. As the centuries passed, decorations became more elaborate as the trade value of the wares increased.

2. MOGOLLON: While the Anasazi primarily occupied northern Arizona and New Mexico, the Mogollon lived in a wide strip along the ArizonaNew Mexico border that continued south more than a hundred miles into Mexico. They made crude brown pots as early as 200. Early on, they added corrugated surfaces, incised decoration, and surface polish, and by 600, painted designs in red. By 1000, northern Mogollon and Anasazi had merged to the point where differences between the cultures began to disappear, and the Mogollon began making black-on-white pottery.

1. ANASAZI Lino Gray, Kiatuthlaana, Chaco, and Mesa Verde Black on white.

2. MOGOLLON Alma Plain, Three Circle Neck Band, Mogollon Red on brown, Three Circle Red on white, Mimbres Boldface, Mimbres Classic.

3. HOHOKAM Vahki and Gila Plain, Snaketown, Gila Butte, Santa Cruz and Sacaton Red on buff, Gila Red, Casa Grande Red on buff.

4. HOPI Jeddito Black on orange, Jeddito Black on yellow.

5. CIBOLA Tularosa Black on white, St. Johns and Pinedale Polychromes.

6. CASAS GRANDES Playas Red Incised.

7. SALADO Salado Red, Pinto Polychrome, San Carlos Red on brown.

3. HOHOKAM: If the Mogollon werent the earliest serious potters, the Hohokam of southern Arizona were. By 500, they were making a distinctive red-on-buff ware that persisted for almost a thousand years.

4. HOPI: Shortly after 1000, the Hopis of north-central Arizona began to emerge as a separate group, identified by their yellow pottery.

5. CIBOLA: By 1100, the Anasazi and Mogollon had merged, and anthropologists gave the culture a new name: Cibola. After 1200, a new redware style replaced black on white.

6. CASAS GRANDES: This southern Mogollon culture persisted in northern Mexico until the sixteenth century. Its glory days show up in the next timeline.

7. SALADO: The Salado made redware in the mountains east of the Hohokam, with whom they quickly merged. The two cultures imitated each others pottery until the Salado turned to black, white, and red.

EVOLUTION, PART II: CREATIVE EXPLOSION, QUICK DECLINE

Pottery flourished during the fourteenth century. Trade and prosperity had reached a high point across the Southwest, but the good times didnt last. Populations dropped, the Hohokam, Salado, and Casas Grandes cultures dispersed, and the Pueblos we know today took shape. Under the Spanish after the seventeenth century, Indian-to-Indian trade largely disappeared, and pottery production reached a low point.