BASE BALL

IN

HOT SPRINGS

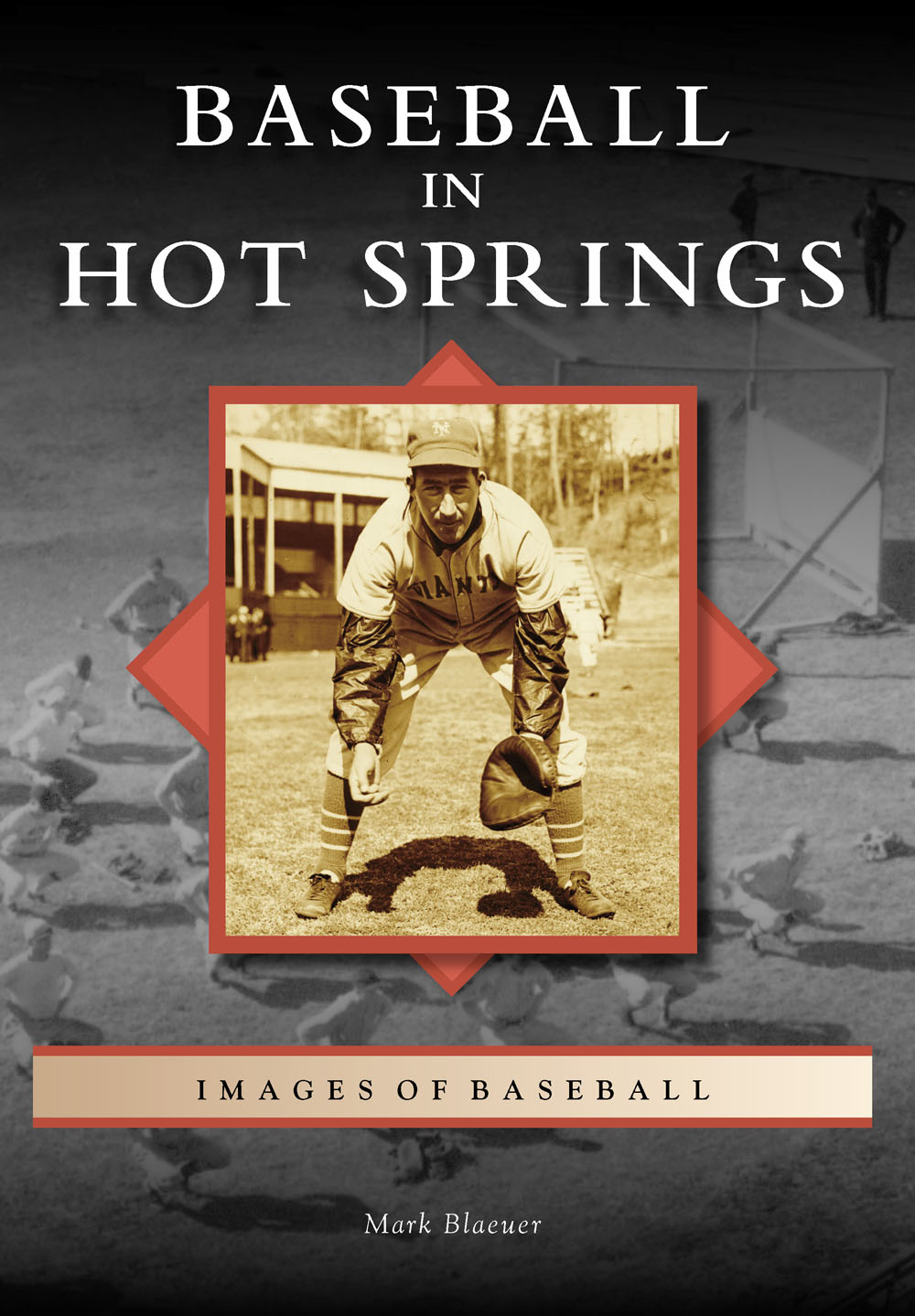

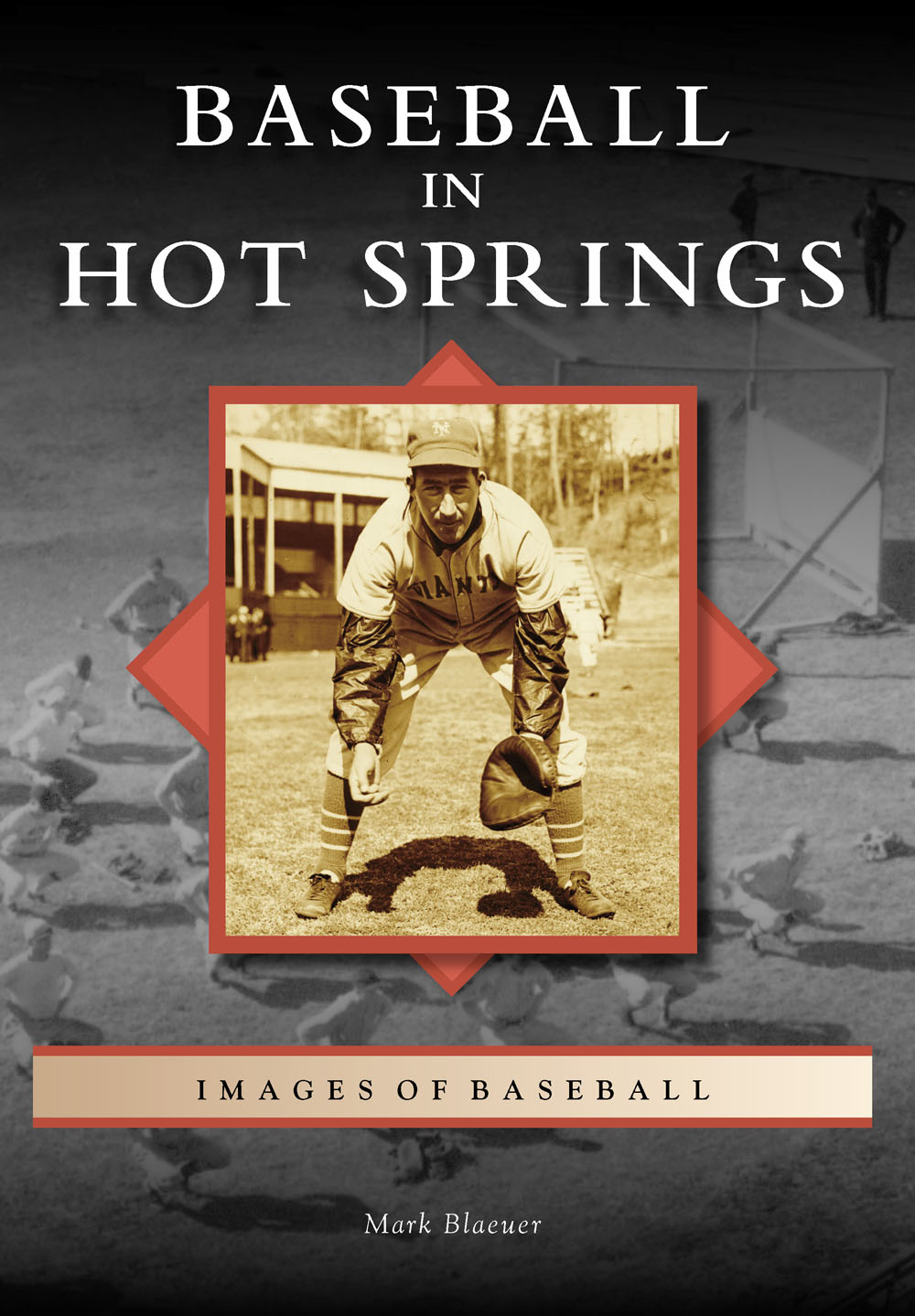

ON THE FRONT COVER: New York Giants catcher Harry Danning trains at Whittington Park in February 1938. (Courtesy of the Garland County Historical Society.)

COVER BACKGROUND: Instructors and students of Ray L. Doans All-Star Baseball School perform setting-up exercises at Whittington Park in February or March 1934 or 1935. (Courtesy of the Garland County Historical Society and the Arkansas Gazette.)

ON THE BACK COVER: The 1948 Hot Springs Bathers finished third in the Cotton States League regular-season standings, with a record of 82-56. The team led the league in attendance. The Bathers became league champions by winning the Shaughnessy (four-team) playoffs. (Courtesy of the Garland County Historical Society.)

BASEBALL

IN

HOT SPRINGS

Mark Blaeuer

Copyright 2016 by Mark Blaeuer

ISBN 978-1-4671-1505-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439655016

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015943733

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

For the baseball players, historians, and fans of Hot Springs.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to thank my wife, Sharon Shugart, who allowed me to monopolize our computer. I have learned a great deal from my Hot Springs, Arkansas, Historic Baseball Trail colleagues: Mike Dugan (who, with Susan Dugan, reviewed the manuscript), Don Duren, Bill Jenkinson, and Tim Reid. Without Steve Arrison, chief executive officer of Visit Hot Springs, there would be no Baseball Trail. In addition, he referred me to Arcadia Publishing. The Garland County Historical Society (Liz Robbins, executive director) generously supported my efforts in numerous ways; Mike Blythe and Clyde Covington took a field trip with me one day to nail down where the George Barr Umpire School photographs had been snapped. Orval Allbritton, Gail Ashbrook, and Donnavae Hughes were always helpful. I am indebted to those who aided me in obtaining images and identifying players therein; along with those already enumerated, these include Gary Ashwill (Agate Type), Dr. Raymond Doswell (vice president of Curatorial Services, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum), Peter Gorton (The Donaldson Network), Caleb Hardwick, McKinzie Lambert, R.J. Lesch, W.L. Pate Jr. (president, Babe Didrikson Zaharias Foundation), Greg Patterson, and Chris Siriano (director, House of David Museum). Others who graciously provided images were Tom Blake at the Boston Public Library, Jeff Bridgers at the Library of Congress, Tom Hill with the National Park Service in Hot Springs, John Horne and Pat Kelly at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as private collectors Jeff Carpenter, Pete Costanzo, and M. Beau Durbin. Thanks to Larry Foley (chair, Walter J. Lemke Department of Journalism, University of Arkansas) and to Tim Nutt (head, Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries) for the rare Hot Springs Arlingtons photograph. Numerous librarians around the country opened their archives or diligently responded to my queries. Thanks to Ray Sinibaldi for clarification and encouragement about copyright issues. I certainly need to thank Jesse Darland, Maggie Bullwinkel, Jim Kempert, and others at Arcadia for their patience and commitment to this project. Despite such copious help from all quarters, imperfections may remain, and those faults are of course mine alone. Finally, I extend heartfelt apologies to anyone whose name and assistance I may have inadvertently omitted.

INTRODUCTION

While nobody knows when the first baseball game occurred in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a huge part of the story began in 1886, when the Chicago White Stockings (later known as the Cubs) of A.G. Spalding and Cap Anson arrived for spring training. They exercised, they bathed in hot spring water (a process considered medicinal and regulated by the federal government), and they played the national sport. They returned several times, and other major-league clubs followed: the Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Spiders, Buffalo Bisons, Cincinnati Reds, St. Louis Perfectos (just before their name was changed to the Cardinals), Boston Red Sox, Detroit Tigers, New York Highlanders (later called the Yankees), Brooklyn Dodgers, St. Louis Browns, Philadelphia Phillies, and New York Giants. The Pirates and Red Sox especially loved the facilities and environment here, returning to Hot Springs quite often.

Minor-league clubs got in on the fun, too. The Denver Grizzlies, Milwaukee Brewers, St. Paul Apostles, Minneapolis Millers, Akron Buckeyes, Indianapolis Indians, and Baltimore Orioles trained here. Other minor-league teams played exhibition games in Hot Springs.

Among various Negro League teams conducting spring training in the great resort town were the Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Baltimore Elites, Memphis Red Sox, New York Black Yankees, Houston Eagles, New Orleans Eagles, and Detroit Stars. Barnstorming tours brought numerous other African American clubs here, such as the Chicago American Giants, Birmingham Black Barons, Indianapolis Clowns, Cleveland Buckeyes, and New York Cubans.

Another club honed its players into shape at Hot Springsa bearded outfit from Benton Harbor, Michigan, known far and wide as the House of David. Sometimes, ballplayers unable to catch on with more orthodox professional teams would sign a contract to tour with the Davids, who were true attractions in their own right.

Hundreds of individual major and minor leaguers, as well as players from the Negro Leagues, traveled here at their own expense, to get into condition for their teams formal spring-training camps elsewhere. Some clubs officially sent smaller contingentsgraying veterans with creaky knees and sore shoulders, pitchers and catchers (the heavers and receivers), or the fat men who needed to boil a few pounds off their girth. They took courses of baths, hiked the mountain trails, and spent lots of time playing golf.

Hot Springs could even boast of its own teams. The most familiar to residents was undoubtedly the Hot Springs Bathers of the Cotton States League, but a full roster of local squads would also include the Hot Springs Vaporites, Vapor City Tigers, and many others.

Where, specifically, did all this baseball take place? The earliest known ball field in Hot Springs, used beginning in 1886 and into the 1890s, was located near Ouachita Street, in the vicinity of where the Garland County Courthouse stands today. This is where the White Stockings played. Whittington Park was constructed in 1894, just northwest of where Whittington Avenue meets Woodfin Street. Also called Ban Johnson Field and McKee Field, it offered a grandstand, bleachers (concrete remnants of which remain on the hillside), and a quirky configuration that evolved over time. It lasted into the 1940s. Majestic Park, the former site of an 1890s horseracing track, was developed in 1909. Located where the Boys & Girls Club of Hot Springs is today, it was later rearranged and divided into fields, including Dean and Jaycee, where the sound of bat meeting ball still rings out. Fogel Field, also known as Fordyce Field and Older Field, was built in 1912. It survives as a vacant field of dreams greenspace behind the Arkansas Alligator Farm & Petting Zoo. Now gone, Highland Park was located on Grove Street. It was used by local African American teams in the 1920s and 1930s. Sam Guinn Stadium, constructed in 1935 on Crescent Street, was the new athletic field for the African American high school in Hot Springs (Langston). The Baltimore Elites trained there in 1944. Greater St. Paul Baptist Church stands on this spot today.

Next page