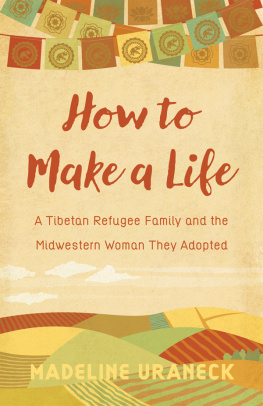

How to Make a Life

How to Make a Life

A Tibetan Refugee Family and the

Midwestern Woman They Adopted

Madeline Uraneck

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

The Wisconsin Historical Society helps people connect to the past by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories. Founded in 1846, the Society is one of the nations finest historical institutions.

Join the Wisconsin Historical Society: wisconsinhistory.org/membership

2018 by Madeline Uraneck

E-book edition 2018

A portion of the sales of this book will be donated to the Wisconsin Tibetan Association.

For permission to reuse material from How to Make a Life (ISBN 978-0-87020-855-3; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-856-0), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

Images are by Madeline Uraneck unless otherwise noted.

The back cover image by Peter Williams shows Migmar and Tenzin in traditional Tibetan dress.

Designed by Integrated Composition Systems

22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Uraneck, Madeline, author.

Title: How to make a life : a Tibetan refugee family and the Midwestern woman they adopted / Madeline Uraneck.

Other titles: Tibetan refugee family and the Midwestern woman they adopted

Description: Madison, WI : Wisconsin Historical Society Press, [2018] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018002467 (print) | LCCN 2018003203 (ebook) | ISBN 9780870208560 (ebook) | ISBN 9780870208553 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Uraneck, Madeline. | TibetansWisconsinMadisonBiography. | Tenzin Kalsang, 1962 | Tibetan-AmericansSocial life and customs. | Women immigrantsWisconsinMadisonBiography. | Single womenWisconsinMadisonBiography. | Single womenFamily relationshipsWisconsinMadison. | RefugeesUnited StatesBiography. | ImmigrantsFamily relationshipsWisconsinMadison.

Classification: LCC F589.M19 (ebook) | LCC F589.M19 T53 2018 (print) | DDC 305.895/41073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018002467

To the memory of my parents, Carl and Barbara Uraneck, who hinted for a story or a poem as a gift for their every birthday, Mothers Day, Fathers Day, and Christmas of my childhood,

to my country school teacher, Dale R. Jordan,

who inspired detailed outlines, multiple drafts, diagrammed sentences,

and responses to five decades of personal letters,

and to Tenzin Kalsang, who smiled when she said, Tibet!

Contents

As I collected the stories shared here, my written notes became repetitive swirls of Tenzins, Pemas, and Migmarsnames that are commonly repeated in Tibetan culture, often within households. The first name Tenzin is especially common because it means someone has been named by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (see page 10 for a more detailed explanation of this process). Most Tibetans have both a first and a second name, with profound, lovely, or religious meanings, but rarely a common last name for the family as is conventional in many other cultures.

Among close family members and friends, a person might be called by just one of their given nameseither the first or second, or by a word that indicates their family relation, such as ani (older sister) or chungpo (younger brother). For example, in the family I came to know, Tenzin Kalsang is called ama-lak (mother) by her children and Tenzin Kalsang by her husband. Her sons, Tenzin Tamdin and Tenzin Thardoe, are usually called simply Tamdin and Thardoe. But when visiting larger groups of family or friends, with many names overlapping, people might use one anothers full names, nicknames, or titles (such as genlak for teacher) to avoid confusion and to indicate respect or affection. Away from the pages of this book, in my interactions with them, I often use their double names, or one name followed by -lak, to make clear my respect. When everyone calls a favorite uncle acho (older brother), however, I find myself doing the same.

For the purposes of this text, I refer to the main members of the family by just one of their given names after giving their full name on first reference, to minimize confusion as much as possible. For some members of the extended family and others who are in the book on a more limited basis, I have used just one of their given names throughout, to help preserve the anonymity of those who did not choose to be written about. Below is a list of recurring names, which should be referred to as needed for reference. Besides trying to balance respect, anonymity, and simplicity, I erred on the side of caution when a few individuals who appear in the book on a limited basis asked that I not use their full or real names at all. Given the nature of their or their relatives political activities in diaspora communities or in the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China, I honored these requests. In these few cases, we agreed upon an alternate name to be used.

Tenzin Kalsang (Tenzin), wife of Migmar Dorjee

Migmar Dorjee (Migmar), husband of Tenzin Kalsang

Namgyal Tsedup (Namgyal), Tenzin and Migmars eldest son

Nawang Lhadon (Lhadon), Tenzin and Migmars daughter

Tenzin Tamdin (Tamdin), Tenzin and Migmars second son

Tenzin Thardoe (Thardoe), Tenzin and Migmars youngest son

Pema Choedon, Tenzins mother

Tsewang Paldon, Tenzins father

Dickey Norzom (Dickey), Tenzins younger sister

Damdul, Dickeys husband in Delhi, India

Migkyi, Migmars sister who was left behind in Tibet

Tseten Lhamo (Acha Lhamo), Tenzin and Dickeys older half-sister

Pema Khando (Khando-lak), Lhamos husband

Tsamchoe, Thardoes host mother in Dharamsala, India

Migmar Wangdu (Wangdu), Thardoes host father in Dharamsala

Lhakpa, Namgyals wife, from Dharamsala

Namdol, Lhakpas older sister in Dharamsala

Samkyi, Thardoes wife, from Bylakuppe, India

Tenzin Choesang (Choesang), daughter of Lhakpa and Namgyal, first grandchild of Migmar and Tenzin

Tseten, Tamdins girlfriend

Jampa Khedup, elder brother of Thardoes wife Samkyi

Tenzin Dechen (Dechen), Lhadons husband, from Nepal

Gawa (Acho Gawa), Migmars nephew, Bylakuppe, India

Choenzom (Ani Choenzom), wife of Gawa, Bylakuppe

Birds fly above and around us every hour of every day, and we barely notice them. But if one flies crookedly, it captures our attention. Those things which are outwardly peculiar are most liable to stimulate our sense, so that we seek the inner meaning.

Jalal Al-Din Al-Rumi, thirteenth-century Sufi Poet, Afghanistan and Asiatic Turkey

If those who journey abroad are categorized as either tourists, travelers, or global citizens, I fall somewhere between traveler and global citizen. Ive taught English in Japan and researched globalization in Morocco. Ive studied dance in Sweden and Poland, worked for the Peace Corps in Central Asia, and have been a Peace Corps volunteer in southern Africa. Whether through work, study, or adventures, I have passed through sixty-four countries. But the most important journey Ive ever taken was one I hadnt even realized I had been on. It began in 1994without an airline ticket, vaccinations, or an itineraryin Madison, Wisconsin.