Afterwords

Eric Meyers

The Use of Archaeology in Understanding Rabbinic Materials: An Archaeological Perspective

The only problem was that over time his theories were strongly opposed and criticized, and while his corpus of material culture remains one of the most important resources for the study of ancient Judaism, there is still no unanimity in how to best understand its significance in the absence of well dated material.

Another influence on my thinking at that time was the sensitivity in Hebrew Bible circles to developing a theoretical framework for assessing the importance of great quantities of new material that were being uncovered in Israel that had direct relevance, so it seemed, on better understanding the biblical story. Indeed, up to this point a very positivist stance had been the hallmark of the American biblical archaeology movement led by Albright, Wright, and Glueck.

and this conference is a testimony to the fact that the dialogue between Jewish material culture and contemporaneous literary sources is now part and parcel of the quest to reconstruct ancient Judaism. The disciplinary separation of archaeology in Israel, however, still remains a major problem and is symptomatic of the continuing desire in some circles to allow archaeology to go its own separate way. I remain committed to the idea that in order to more fully understand the world of ancient culture and Judaism in particular it is imperative to be immersed in the textual material including the visual and epigraphical sources that are chronologically relevant.

: View of Temple Mount from the Air.

The main and most dramatic change that has affected this topic over the past generation is the vast amount of new material that has come to light. This process began most noticeably after 1967 when Israel took possession of territory that was identified with the story of Jewish life after the destruction of the Second Temple in the West Bank. The expansion of the IAA and the number of salvage excavations, and the beginning of new Israeli and foreign excavations, all led to an unprecedented collection of new data, much of which is just being published or becoming known to a wider audience. Indirectly, this new data has allowed the critical scholar to use the Goodenough corpus with a much greater degree of selectivity. Let me select some categories of data that have direct relevance for allowing the student and scholar of ancient Judaism to better understand aspects of rabbinic literature.

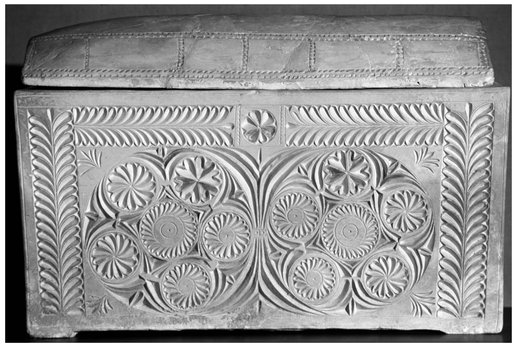

Jewish burial has provided a great deal of data that has illuminated rabbinic materials. Without a decent knowledge of Jewish burial practice in the Greco-Roman period, I cannot imagine how anyone could begin to understand the range of texts that deal with death and burial. We may begin with the important and key change from the Iron Age and Persian periods, the introduction of the coffin or individual burial receptacle in the Hellenistic period along with the ossuary in a slightly later period.

Although Jews continued to bury in subterranean chambers, the inauguration of the separate burial container may have given rise to the idea of individual identity in death, or else been the result of this change in perceptions of the individual. This contrasted strongly with the Iron Age custom of gathering the bones of the dead and placing them in pits or benches in underground tombs, reflected in the Biblical expressions to sleep or be gathered to ones ancestors. Furthermore, in the Hellenistic and Roman periods the containers of the bodies or bones of the dead were often inscribed with the names of the deceased, suggesting that Hellenistic ideas were somehow attached to Jewish beliefs. And though the leading scholar on this subject believes that ossuaries reflect only Pharisaic ideas about life after death,

Identifying a certain form of Jewish burial with a specific belief without the aid of an inscription, however, is very difficult if not impossible. Achieving a better understanding of the sources in the light of the realia, however, is something I think we all could agree on. Such a text would be m. Moed Qatan 1:5: First they were buried in ditches. When the flesh wasted away, the bones were collected and placed in chests. On that day (the son) mourned, but the following day he was glad, because his forbears rested from judgment. In light of recent public discussions about ossuaries and the Jesus tomb, it would seem totally appropriate for scholars of early Judaism who know rabbinics to become more conversant with the archaeology of Jewish burial in Second Temple times and in the Talmudic period.

In connection with the theme of Jewish burial I would like to draw your attention to the insightful article of Yonatan Adler who examines the phenomenon of ritual baths adjacent to tombs. The article is fully informed on material culture and Jewish tombs and miqvaot as a starting point and goes on to examine the appropriate literary sources in the Bible, Qumran, and rabbinic sources. He concludes that such ritual baths were used by funeral participants who had contracted second-degree impurity through an intermediary source (i.e. physical contact with one who had contracted direct corpse impurity). Such an individual could be purged from that impurity on the very day in which it was incurred as opposed to a seven-day purification process. Adler offers that the large size of the ritual baths at the Tomb of the Kings in Jerusalem and at Bet Shearim may be explained as accommodating those leaving a funeral, and in these two cases, the individuals were upper class.

Another category is that of foodways. I think it is important for literary scholars of rabbinic materials to know that recent research of faunal specialists in collaboration with archaeologists has confirmed that at important Jewish sites and in areas that are exclusive to Jewish occupation, the absence of pig has been established beyond any shadow of a doubt and consequently interpreted to be proof of a Jewish presence or occupation. Stuart Miller has pointed out the text in b. Baba Metsia 24a that demonstrates the relevance of such research: In a discussion of the kashrut of a slaughtered animal that has been found, it is decided that the area of the find is determinative (of its comestability). That is, if the animal was found in a place known for its Jewish settlement, such as the area between As in modern research, then, where there is a correspondence between archaeological realia and the text we have a strong case for establishing the religious identity and ethnicity of a given population. This may not seem like such a great discovery or insight to some of you, but I can assure you that in late antiquity, in particular at urban sites with churches, synagogues, and pagan temples, it is not always easy to distinguish one group from the other when it comes to examining domestic or even industrial units. Careful examination of faunal remains thus could be most helpful in determining the makeup of small villages on the perimeter of major Jewish settlements or even of villages at a remove from such centers as in the Golan, and we indeed have identified Jewish sites from the Hellenistic and Roman periods that have produced non-kosher items such as hyrax, camel, catfish, and even small remains of pork. Whether such a site had a non-Jewish element or whether Jews consumed such items is an issue well worth pursuing in the future.