TAKING THE HEAT

TAKING THE HEAT

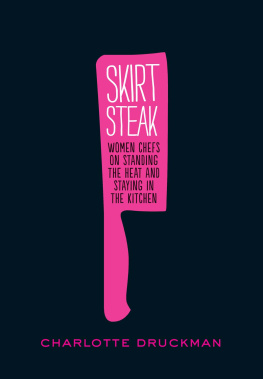

Women Chefs and Gender Inequality in the Professional Kitchen

DEBORAH A. HARRIS AND PATTI GIUFFRE

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harris, Deborah Ann.

Taking the heat : women chefs and gender inequality in the professional kitchen / Deborah A. Harris, Patti Giuffre.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8135-7126-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8135-7125-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8135-7127-0 (e-book (web pdf)) ISBN 978-0-8135-7554-4 (e-book (epub))

1. Women cooks. 2. Food service. 3. Women in the hospitality industry. 4. Women in the food industry. 5. Sex discrimination against women. I. Giuffre, Patti, 1966 II. Title.

HD6073.H8.H37 2015

331.4'816415dc23

2014035985

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2015 by Deborah A. Harris and Patti Giuffre

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

Visit our website: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu

Manufactured in the United States of America

We would like to dedicate this book to

Ella Harris and Tim Paetzold

Contents

We wish to thank the thirty-three women chefs who agreed to participate in our research. We are in awe of the women chefs and their strength, dedication, and passion for cooking. They generously shared personal details about their work and family lives, and this book would have been impossible without their help. We would also like to thank our editor at Rutgers University Press, Katie Keeran. We are extremely grateful for her support and excitement about the project. Thanks also go to Leslie Mitchner and Nicole Manganaro at Rutgers University Press for their help finalizing the book.

This book has been a work in progress for a few years now, and several people gave us feedback and support along the way as we formulated different aspects of the book as conference papers and articles. Several graduate students helped us find literature and data. We thank Raul Casarez, Jamie Hornbuckle, Kelley Russell-DuVarney, Whitney Harris, Alyssa Powell, and Tracy Quiroz. We thank Deborahs friend who fancied up , Suzanne Daniels. We are grateful to friends and colleagues who commented on the proposal, previous articles, papers, or chapter drafts: Kirsten Dellinger, Christine Williams, Dana Britton, Patricia Richards, Gretchen Webber, Ellen Slaten, Jessie Daniels, and Vanina Leschziner. We would like to thank John Bartkowski for his suggestions about precarious masculinity. Thanks to our colleagues at Texas State University including the Department of Sociology (particularly Dr. Susan Day, our department chair, and Tina Villarreal, who assisted us in some of the technical aspects of producing the book), College of Liberal Arts (particularly Dean Michael Hennessy), and the Office of Academic Affairs (particularly Associate Provost Cynthia Opheim), whose financial support for subvention costs made this book a reality.

We also offer more personal thanks to our dear friends and family members who provided us with emotional support over the duration of this project. Deborah would like to thank her mother, Ella Harris, for demonstrating what tenacity and verve look like. She would also like to thank her sisters, Gwen Gibbs, Angela Stanford, and Susan Williams, for all their love and support. Several friends have provided encouragement and counsel during this process. Kristi Fondren, Diana Bridges, Aerin Toussaint, Maggie Schleich, and Jamie Smith have all heard more about women chefsand the process of writing about themthan anyone should ever have to hear. You can all expect copies of this book and Deborah really hopes they arent immediately thrown in a paper shredder. Deborah would also like to thank the supportive ladies from the Feminist Kitchen Book Club, particularly founder Addie Broyles, for their enthusiasm and interest in studying women chefs. She would also like to thank Virginia Wood for her helpful comments early in the planning of this project.

Patti would like to offer her utmost gratitude to Tim Paetzold, whose confidence in her never wavered. This book would not have been possible for Patti without Tims love, faith, and support. She would also like to thank her dear friends and colleagues, Kirsten Dellinger, Christine Williams, Julie Winterich, Ellen Slaten, Jeff Jackson, Michelle Reese, Michelle Roebuck, Steve Roebuck, Beth Bertin, and John Baker who read drafts, offered suggestions and insight, made her laugh, required her to dance occasionally, and always offered a bright light in her life. Finally, she would like to thank Ginger and Neil Whitesell, Perry Giuffre, and Pat Paetzold for supporting her academic work for many years. Patti is eternally grateful for her friends and family who are constant reminders of what is important in life.

We thank Emerald Publishing and Springer Publishing who gave us permission to include some of our work from previously published articles. Portions of were based on our 2010 article, The Price You Pay: How Female Professional Chefs Negotiate Work and Family, Gender Issues 27:2752.

TAKING THE HEAT

For the past three years, champagne maker Veuve Clicquot has sponsored a Worlds Best Female Chef Award. When the company announced that the 2013 winner was Italian chef Nadia Santini, the praise for Santini, who was the first woman ever awarded three stars by the prestigious Michelin Guide, was tempered with criticism about the merits of singling women out for a special award. Anthony Bourdain, the chef-turned-television host, asked via his Twitter account, Whyat this point in historydo we need a Best Female Chef special designation? As if they are curiosities? Other chefs and influential food writers have also commented on having separate designations for men and women chefs and suggested doing away with woman-centered awards. They argued that reserving a special award for women is divisive and implies women have to be evaluated differently, and, it is often suggested, less stringently, than their male peers.

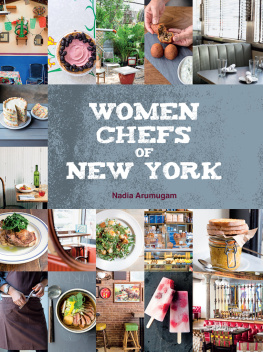

These remarks are just part of a larger discussion about womens place in the (professional) kitchen. Underlying these responses, however, is the fact that women chefs are sometimes regarded as curiosities, much like women in many male-dominated careers. While there are several rock star men chefs so famous even the most casual foodie knows who they are by first name alone (Emeril, Mario, Wolfgang), lists of accomplished women chefs are harder to provide. As gender scholars who focus on the role of work in perpetuating and challenging gender inequality, we were fascinated by the case of women professional chefs and the numerous contradictions they face in their work lives. How is it that womenthe gender most commonly associated with food and cookinghave lagged so far behind men in professional kitchens?

We soon discovered that answering such a question was more difficult than originally thought. Understanding the gendered nature of the culinary world involves examining the history of professional chefs, the influence of cultural intermediaries such as food critics and writers who are tasked with evaluating and promoting food created by chefs, and the experiences of women chefs working within male-dominated workplace cultures. When examined together, these conditions can tell us something about how certain jobs become coded as masculine and feminine and, therefore are perceived as mens or womens work. Studying women chefs can also help identify the mechanisms and processes that allow these gender disparities within occupations to continue and highlight strategies that allow more gender integration to occur.