Early American Places is a collaborative project of the University of Georgia Press, New York University Press, Northern Illinois University Press, and the University of Nebraska Press. The series is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.earlyamericanplaces.org.

A DVISORY B OARD

Vincent Brown, Duke University

Andrew Cayton, Miami University

Cornelia Hughes Dayton, University of Connecticut

Nicole Eustace, New York University

Amy S. Greenberg, Pennsylvania State University

Ramn A. Gutirrez, University of Chicago

Peter Charles Hoffer, University of Georgia

Karen Ordahl Kupperman, New York University

Joshua Piker, College of William & Mary

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Rosemarie Zagarri, George Mason University

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Baumgartner, Kabria, 1982 author.

Title: In pursuit of knowledge : black women and educational activism in antebellum America / Kabria Baumgartner.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: In Pursuit of Knowledge explores Black women and educational activism in Antebellum AmericaProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009450 | ISBN 9781479823116 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: African American women educatorsHistory19th century. | African American women political activistsHistory19th century. | African AmericansEducationHistory19th century. | African AmericansSocial conditions19th century. | United StatesRace relationsHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC LC2741 .B38 2019 | DDC 371.829/96073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009450

In the spring of 1833, twenty young African American women trekked to the Canterbury Female Seminary located in the town of Canterbury, Connecticut. They were overjoyed to partake in this opportunity for advanced schooling. But white Canterbury residents were far from joyful; in fact, they sought to drive these young women out of the town. After seventeen months of continuous harassment, abuse, and even violence, white residents got their wish as the Canterbury Female Seminary closed in September 1834. This incident marked yet another unfortunate case of northern racist violence, but it was more than that too: it reveals a larger, more complex story of African American girls and women in pursuit of knowledge in nineteenth-century America.

The controversy surrounding the Canterbury Female Seminary galvanized African American women activists, who penned essays on the value of education, set their sights on building schools, and entered the teaching profession. Sarah Mapps Douglass, an African American teacher and school proprietor in Philadelphia, was certain that education opened a path to civil rights and economic betterment. In a public letter, she offered a powerful motto to guide African American girls and women: Be courageous; put your trust in the God of the oppressed; and go forward! In her estimation, educated and pious African American girls and women ought to live their lives with a sense of purpose.

In Pursuit of Knowledge examines the educational activism of Douglass and other African American women and girls living in the antebellum Northeast. Activism is broadly defined here to capture the forms

Students and teachers like Sarah Harris, Mary E. Miles, Serena deGrasse, Rosetta Morrison, Sarah Parker Remond, Susan Paul, Sarah Mapps Douglass, Charlotte Forten, and others were educational activistseach a pioneer and forerunner in her own way. Collectively they pushed for racial (and often gender) inclusion at a time when many white Americans considered the very idea of a multiracial democracy to be contrary to the good of the nation. Eschewing a strict division between public and private spheres, these African American women activists viewed the schoolhouse as both an extension of the home and a defining civic space. They framed their argument for educational inclusion as a matter of equality and rightshence this books use of the phrase equal school rights to describe their efforts.

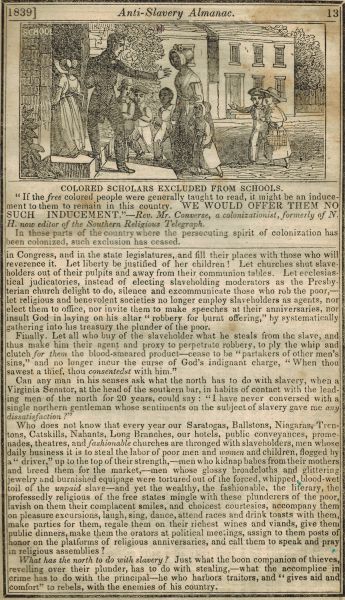

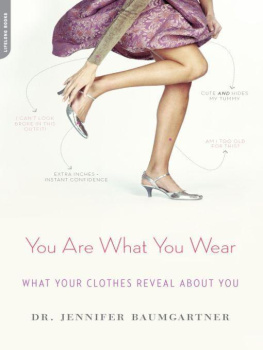

Colored scholars excluded from schools. This illustration from the American Anti-Slavery Almanac (1839) depicts a man apparently barring an African American mother from leading her children into a schoolhouse. Authors collection.

During the nineteenth century, schools became sites of productionto make Americans, to turn poor white boys into ministers, or to prepare white women for civic life. The historian Hilary Moss describes public schools of this period as an Americanizing agent, an institution whose central purpose was to fuse children from all religions and ethnicities into a single American citizenry. The education of white men, women, and children thus flourished as schooling became increasingly bound up with social, political, and cultural obligations. African Americans, however, were considered unworthy of such responsibilities. A process of racialization was embedded within the very notions of childhood, womanhood, manhood, education, and citizenship.

Despiteand, perhaps even more intensely, because ofthis exclusion, African American girls and women had educational ambitions that framed their very sense of womanhood. The historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar finds that many middle-class African American women in Philadelphia and New York City proved their respectability by their appearance, conduct, and education.

What emerges is the significance of another idea shaping African American womens actionsnot just the well-documented demand for respectability but also the related yet distinct call for purpose. Purpose held different meanings for different people; for some, it meant proselytizing, pursuing meaningful work, expanding the mind, and leading a respectable life. Both men and women used the term, as did whites and African Americans. In fact, some white women teachers in the antebellum era linked their Christian faith to a notion of usefulness. But the racial and gender oppression under which African American women struggled gave purposeand purposeful womanhood more specificallya different meaning. African American women talked about leading a purposeful life not simply to rationalize their access to advanced schooling but to motivate more young women to value themselves and to do something of value in a world that failed to recognize them as valuable.

A purposeful woman was resilient, enterprising, and activea proud seeker of knowledge. Though the ideology of purposeful womanhood came with some restrictions, it still offered a more capacious definition of domesticity, piety, and activism since it was specific to the experiences, actions, words, and thoughts of African American girls and women in a way that the ideology of the cult of domesticity, with its racial entanglements, never could be. Purposeful womanhood afforded African American girls and women the opportunity to study, to write, and to pursue knowledgeas activists, educators, community members, leaders, and, most of all, human beings.