T HERES NO DOUBT ABOUT IT, said the doctor, The bronchitis you suffer each winter is due to your war service.

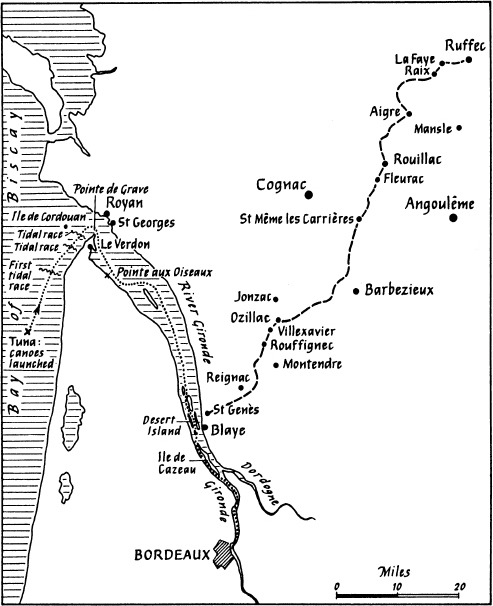

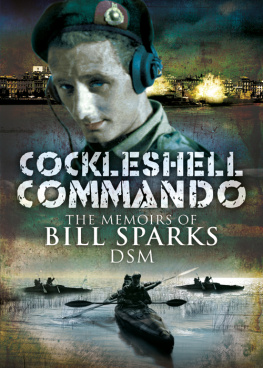

This was not something that came as a bolt out of the blue to me really. Ever since the day I fell into the sea while stationed in Iceland during the war and caught bronchial pneumonia, I had gradually begun to suffer. But I wasnt bitter at all. I had played my part in the war. I was one of the so-called Cockleshell Heroes and had been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for my part in Operation Frankton. My medal had become my most treasured possession, presented to me personally by King George VI.

What do I do now? I asked the doctor.

Well, you can apply for a war disability pension, and you may have to consider early retirement.

I made my claim and underwent investigation to ascertain that my disability was due to war service. I was suitably graded and then informed that, whilst responsibility by the Military was accepted, my grade did not qualify me for a pension.

In due course, I retired. My wife, Rene, and I dreamed of buying a house in the country, and we set our hearts on a bungalow in Sussex. We placed a deposit, having decided we could afford it if we handled our affairs carefully, and moved in. I had a reasonable pension from my employers, London Transport, for whom Id been a bus driver, a bus inspector and finally a garage inspector, and I had my state pension. We could just manage.

Then came a terrible blow. The Government decided to reduce my state pension by 1,000 a year. My wife and I were thunderstruck at the thought that we could lose our home. We racked our brains trying to see how we could cope on 1,000 less a year. Finally we realized that we would have to sell something to make up the difference.

With great reluctance, I put a call through to Sothebys and asked them if they would auction my most prized possession my medal.

Before long, newspapers were carrying the story that the last of the Cockleshell Heroes was compelled to sell his medal. After that, hundreds of letters of support poured in. Most said how outraged they were that my pension should have been cut. One young man telephoned me in tears, saying how disgusted he was with the way I was being treated, and he offered to give me 10 a week out of his own wages. Close to tears myself, I declined his kind offer.

I had another offer by telephone from a gentleman living abroad who offered to send me 12,000 providing that I did not sell the medal. It was generous of him, but I could not accept charity.

The day of the auction arrived and Rene and I boarded the train for London. And as we sped along I recalled that years earlier I had taken another train ride to London, at a time when the world was at war.

The train rumbled on through the night. Looking out into the darkness of the countryside, I could not see so much as a single twinkling light as England was plunged into total blackout. If Hitlers Luftwaffe were in the skies tonight, I saw no sign of them, nor heard them above the clatter of the train. Except for the inky blackness it was almost as though, for a brief while, England was at peace, banishing all thoughts of war for myself and two of my shipmates from the Renown one a Marine and the other a stoker and, like myself, a Cockney.

We had been cooped up on the train since the previous day when wed boarded at Edinburgh; the Renown and the long search for the Bismarck were left far behind. Ahead lay fourteen wonderful days leave in London. It was a long time since Id been home; a long time since Id seen Dad.

Dear old Dad. I thought he was going to kill me the day I joined the Royal Marines. I had originally decided, at the outbreak of war, to follow Dads footsteps; hed been a stoker in the Royal Navy at the time I was born on 5 September, 1922 the country was then still reeling from the General Strike. In 1939, when the storm clouds were gathering over Europe, I took myself off to the local recruitment office to join the Royal Navy. However, a sergeant there convinced me I was too intelligent a lad for the Royal Navy. He produced brochures featuring exciting photographs of smart young Marines wearing their lion tamer tunics and gleaming white helmets, standing beneath palm trees on some exotic island, surrounded by beautiful girls in grass skirts. He convinced me; this was the life for me.

I was led into another room for a medical examination. Passed fit in every respect, I was handed a Bible, sworn in and given half a crown.

You are now a Royal Marine recruit, lad, beamed the sergeant. Now you go on home and wait for your call up.

Proud as a peacock, I marched smartly home; but my steps faltered as I was suddenly struck by the thought of confessing to Dad that I had joined the Marines without consulting him.

I waited with apprehension for Dad to return home from work that evening. He came in through the door and, summoning up all my courage, rather haltingly, I told him what I had done.

What? he exploded. You stupid little so-and-so, I ought to knock you from here to next year And he continued in that vein for a while until a thought occurred to him. He quietened down and, still furious, said, Youre still only seventeen. When the papers come through Ill refuse to sign them. Thatll put a stop to all this nonsense.

I didnt have the courage to tell him that his signature would not be required.

And so in 1939, as a young Marine recruit, I had caught the train from Charing Cross to attend training camp in Deal. Now I was returning three years later as a full Marine who had seen action in the Mediterranean. But I still hadnt seen a single girl in a grass skirt.

Morning came as we hit the outskirts of London. Our excitement rose and we talked of the days ahead, of the families wed not seen for so long, of the reprieve from battle, and the simple thought of how lucky we were to be home. Then we hit North London and our joy was diminished by the view from our carriage of a city that had endured nightly punishment. Everywhere were piles of rubble that had been houses, shops, factories, theatres, even churches. Slowly pulling into Kings Cross station, we passed railmen filling in bomb craters and repairing buckled track.

The train came to a juddering halt. We cheered up, eager to get home, and climbed out onto the platform. At the ticket barrier, reunited sweethearts kissed and hugged and returning sons embraced their parents. For others, about to board the train, it was a moment of heartbreak and farewell.

Outside the station we found ourselves in the middle of a war-torn city. Many buildings were pockmarked or blackened by fire, and the roads were peppered with craters. Facing the enemys bombs and bullets was an everyday occurrence for me and my shipmates, but at least we had the comfort of being able to fire back. All our civilians could do was take shelter and hope for the best. Yet even amid this destruction, people were going about their daily business; shops were open, the buses and tubes were running an abnormal existence had been turned into normality. Clearing the rubble and filling in the craters had just become part of the way of life. To servicemen like ourselves returning from combat zones, this was a revelation. These were non-combatants standing up to combat, and their spirit was unbroken. We felt very proud of them at that moment.