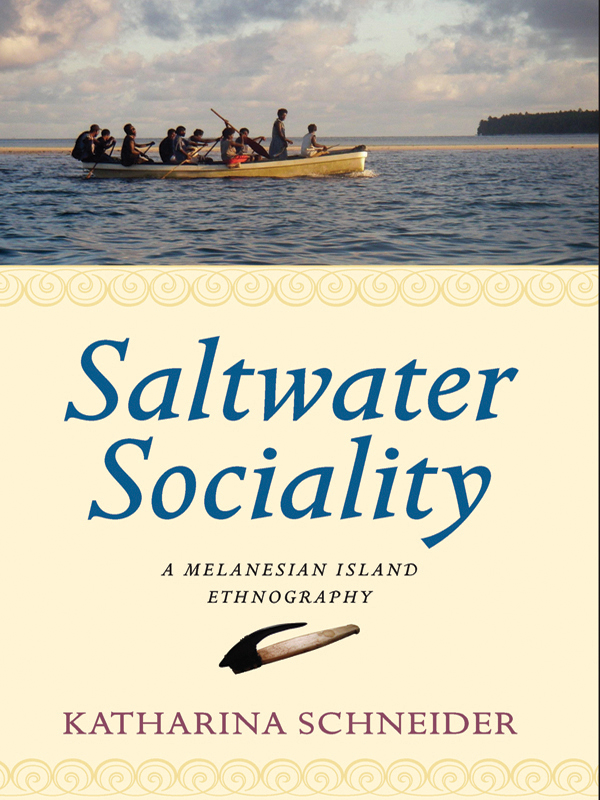

SALTWATER SOCIALITY

A Melanesian Island Ethnography

Katharina Schneider

Published in 2012 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2012 Katharina Schneider

First ebook edition published in 2012

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schneider, Katharina.

/ Katharina Schneider. 1st ed.

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-85745-301-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-85745-302-0 (ebook : alk. paper)

1. EthnologyPapua New GuineaBougainville Island Region. 2. Matrilineal kinshipPapua New GuineaBougainville Island Region. 3. Bougainville Island Region (Papua New Guinea)Social life and customs. 4. Bougainville Island Region (Papua New Guinea)HistoryAutonomy and independence movements. I. Title.

GN671.N5S33 2012

306.099592dc23

2011037824

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-85745-301-3 (hardback)

ISBN: 978-0-85745-302-0 (e-book)

TABLES

| Chapter 1 |

| . |

| Chapter 4 |

| . |

| Chapter 5 |

| . |

| Appendices |

A NOTE ON LANGUAGES

The fieldwork on which this book is based was conducted in two languages, which are commonly mixed on Pororan. One of these languages is Papua New Guinea Pidgin, or Tok Pisin. The other language is Hapororan, the local language spoken on Pororan and Hitou Islands. Hapororan words and phrases are italicized, and Tok Pisin words and phrases are underlined in the text.

Key ethnographic terms are rendered in the original language in the text, following the example of several earlier ethnographers working in the area. The translations that are sometimes used locally for conversations with foreigners are over-used and carry unwanted connotations in anthropology, and I have thus avoided them. Furthermore, keeping the original terms will make the text more useful for people with ethnographic or other interests in the Buka area. All these terms are explained in the text. For consistency, Hapororan terms are used even where reference is made to my own or other ethnographers' research in other Buka language areas. Where the Halia and Haku terms differ from Hapororan onesas they usually do only very slightlythey are noted in the glossary.

Furthermore, there are some words and phrases that Pororan Islanders used either very frequently or emphatically, the exegesis of which has contributed to the development of my argument. I often, though not always, render these terms in the original, both in order to highlight their importance to the ethnography and to establish connections across the text. A translation is given in brackets when a word is first used. All words are also listed, and are either translated or briefly explained in the glossary.

My Tok Pisin spelling is based on local usage, as learned from notice boards in Buka Town and from hymn lyrics handed out during mass on Pororan. My spelling of Hapororan is based on teaching material used at the Pororan elementary school. It diverges in two points from the spelling used in Beatrice Blackwood's (n.d.) Petats vocabulary list and two gospel translations, one by the London British and Foreign Bible Society (1934) and one by the Summer Institute of Linguistics (1976). A vowel pronounced as a closed English o or ou is written o. A diphthong between the English ch and ts is written ts. There are no plural markers in Hapororan, and none have been added here.

PREFACE

In July 2004, I went on a first visit to Pororan Island, a small island on the fringe reef of Buka Island in Bougainville, a region in the far east of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Colin Filer and Mike Bourke at Australian National University had suggested Pororan as a field site for doing research on saltwater-bush relations in Melanesia, as I had told them I wanted to do. Colin had put me in touch with one of his former students, Roselyn Kenneth, from the Haku language area in northern Buka. Roselyn was working at the United Nations Development Project office in Buka Town in 2004. She picked me up from the Buka airport and put me up in the spare bed in her room in Town. A few days later, as part of a broader round of introductions among her colleagues, relatives and friends, Roselyn introduced me to her uncle Lawrenceneither of them was clear about how exactly they were relatedfrom Pororan, who was running a hotel and restaurant in Buka Town and whose house on the island stood empty. Lawrence seemed to like the idea of me staying there. He said he would be glad if I could keep an eye on his mother there, who tended to over-work herself in an attempt to defy aging. About a week later, Lawrence asked his brother Albert to take Roselyn and me along when he left for Pororan on his fibreglass boat, powered by a 60-horsepower outboard motor. Albert agreed, and Roselyn and I packed a few things and enjoyed a pleasant two-hour journey across the lagoon.

We approached Pororan just as dark was falling. Roselyn deeply inhaled the smell of grilled fish that hung over the island, spoke about her memories of Pororan and imagined what it would be like for me to live there: Ah! Pororan is a fishing place. We used to come here as children, I remember, for eating fish. We stayed with our relatives and ate and ate and ate. You can never get this much fish on the mainland. Smell it! she said to me. You will grow fat on Pororan fish if you stay here, lucky you! Just be sure to go and see my mother at the market at Kessa [at the northwestern tip of Buka Island, where Pororan and Hitou Islanders exchanged fish for sweet potatoes and other garden produce every Saturday in 2004]. You can bring her some fish, and she will give you sweet potatoes. Otherwise you will not have any sweet potatoes to eat. The Pororans don't have enough sweet potatoes. Their gardens are too small. This island is tiny, you know. So make sure you don't miss the market. My first thought was that I hadn't even got a fishing line yet. Roselyn seemed to have read my thoughts as she said: Of course, mama will be happy, too, if you give her money instead of fish. Certainly until you have settled in on the island and learned how to catch fish over here.

A few boys who had come to greet the boat led Roselyn and me to the hamlet of Kobkobul, where we met Lawrence's mother, Roselyn's bubu [grandmother], the old lady Kil. Kil was in a rage. Where are my forks? she shouted in Tok Pisin, whizzing through the hamlet from one kitchen table to another outside different houses. She cleared a fishing basket off a bench to look underneath, cursed her daughter Denise who was away at this crucial moment when she needed to find forks for her visitors, and hit at her giggling grandchildren who were getting in her way. Oh, I have visitors, and the forks are not there, she lamented. This woman from Haku, I have not seen her forhow many years? I thought she had forgotten all about her old grandmother on Pororan! I did not even know if she was still alive! You, how are you? she asked Roselyn almost accusingly and wiped tears off the corner of one eye. You and your sisters, and your old mother, that woman Ngasi? I never see her, she never comes round to visit, did they mess her up over there? It was only much later that I learned to understand this as a reference to sorcery. Roselyn was listening patiently for a while, but then her eyes started dancing nervously. Finally, she managed to interrupt Kil's lamentation: Mama is fine, bubu . We are all fine. Here, I have brought you some sweet potatoes, she said and pointed to a basket that we had bought in Buka Town in the morning. Kil threw a glance at the basket and was off onto another topic, sitting down now but not losing momentum in her speech. This is not very much. You know, we have been hungry on the island. For four months, we have been hungry now. Your people in Haku, they have been greedy with their sweet potatoes. The markets have been very bad. Too few sweet potatoes. Our fish, we had to take it back with us. It rotted on the way back in the sun. Not enough sweet potatoes. You tell your mothers and sisters to bring some sweet potatoes to the market, for their relatives on Pororan. You know, I am glad I have two good sons working in Town. They are good boys, Albert and Lawrence, they help me, they send rice. Indeed, Albert had dropped a big bag of rice off along with Roselyn and me. Without the rice, I don't know what we would do, Kil added. Roselyn quickly told me that the past four months had been extremely hard for everyone in Buka, as bad weather had spoiled the sweet potatoes in the ground. Her relatives had had trouble keeping themselves fed, and there were no leftovers to take to the market and exchange for fish.