Not Forgotten

A Natural-Born Linthead

BY JL STRICKLAND

My parents story was not uncommon. It was repeated by countless other young people in the first half of the last century. They had their pictures made in front of the mills to commemorate their arrival in a strange land and a new beginningin my parents case a beginning that would lead to four generations of my family working in the West Point Manufacturing textile plants. JL Stricklands mother at the Fairfax Mill, c. 1940, courtesy of the author.

In my mothers picture box was an old black and white photograph of her and my daddy as a smiling, young Alabama working-class couple, wearing their Sunday best. They were standing across from the village kindergarten, at the south end of Fairfax Mill where they both worked, along with thousands of other employees. The cotton mill, a blue-paned, three-story, red-brick monolith, rose grand and mighty in the background, and they seemed small and shy before it; and incredibly young and happy.

I am sure many Chattahoochee Valley families have a similar photograph in their family albums; my parents story was not uncommon. It was repeated by countless other young people in the first half of the last century. They had their pictures made in front of the mills to commemorate their arrival in a strange land and a new beginningin my parents case a beginning that would lead to four generations of my family working in the West Point Manufacturing textile plants.

Like many Valleyans, my parents grew up in rural Randolph County, Alabama, and joined a steady migration of friends and relatives to what everybody simply knew as the Valley, which lay hard against the Georgia line in eastern Alabama, seeking jobs and a better life, and they found it. They left backwoods farms, that were basically unchanged since the 1800s, for a mill house with electric lights, running water, coal fireplaces, and an inside toiletthey never had it so good. They might as well have been on another planet.

Riverdale and Langdale were the companys first mills, starting production in 1866, powered by water wheels turned by the Chattahoochee River. The founders of what was to become West Point Manufacturing were area planters, merchants, and former Confederate soldiers who started two cotton mills with money scavenged from the smoke and rubble of the Civil War. One of the mightiest textile manufacturing enterprises in the history of the world began as much with desperation as with hope; as it turned out, Providence smiled on their bold venture. By the early 1900s, West Point Manufacturing owned five Alabama mill villages in the Chattahoochee Valley. Each of the villages was built around its own mill, starting with Lanett at the northern end, and then, in descending order, Shawmut, Lang-dale, Fairfax, and Riverdale. The mills were electrified and no longer depended on waterwheels for power.

The boundaries between each village were amorphous, with one blending into the other, but each mill village possessed a strong self-identity that fueled fierce rivalries, mainly concerning their respective athletic teams. Their baseball teams, particularly, were revered and supported with a near religious fervor. (In later years, Valley and Lanett High Schools would produce a steady supply of football players for the college and professional ranks.) Of such intensity were the animosities that a wedding between residents of different villages was seen as a mixed marriage.

Each West Point Manufacturing Company mill village was a self-contained universe of employee housing, churches, schools, grocery and drug stores, cafs, barber shops, beauty parlors, shoe repair shops, filling stations, dry cleaners, doctors, including chiropractors, and picture shows. A person could live without ever setting foot off the mill village, if so inclined. (Indeed, it was rumored that the only way some mill village folk could find West Point, Georgia, the mill company headquarters a few miles away across the state line, was to follow the Chattahoochee Valley Railroad tracks out of town.) The only item not easily obtainable was alcohol. Because of the teetotalers who ran the Valley, strong spirits were prohibited. But they were available, if you knew the right personand most people knew that person, and several more just like him.

It was a time and a place that we shall never see again, and it was not by any means a bad place. While Im not nave enough to claim that a mill village was the best place to grow up, I feel comfortable in saying that it was certainly not the worst place in the world, not in the Valley anyway. I loved growing up in the leafy, tree-covered Fairfax Mill Village, and I loved the people in it, with a few exceptions who shall forever remain nameless. And I loved the dry, sweet smell of the cotton mill, and the sounds of the spinning frames singing, looms rhythmically rocking, and air compressors thumping 24 hours a day. The mill was the beating heart at the center of that insulated world.

Living in the village and working in the mill was not dwelling in Beulah Land, not by a long shot. As in any human endeavor, the humans doing the endeavoring can be problematic. There were good jobs in the mill; unfortunately, there were also the bad jobs, and neither of them paid enough for the sweat, aggravation, and effort required. Furthermore, some of the bosses shouldnt have been put in charge of a pack of gopher rats. Non-union workers are at the mercy of every management whim and foible, no matter how ridiculous or mean-spirited. Like politics does with bedfellows, nepotism and golfing buddies make for strange mill bosses. But, there was job security with the company, if you stayed in line; and you could feed and clothe your family and have pocket money left, if you didnt try to get too big for your overalls. And my waistline is living proof that I never missed a meal. Mill villages were a prime example of company-town paternalism: a type of benign quasi-slavery with a baseball team and a picture show.

As my parents generation grew older and established families, many of them, while appreciating their comparatively improved station in life, wanted better for their children. It was as if by moving off the farms to the mill towns they realized that a better life was possible for people who planned and acted accordingly and didnt accept the status quo. Looking back, I can remember many of the parents of kids I knew encouraging their children to look farther than the mills, just as their parents had encouraged them to look beyond the hardscrabble farm. In many cases, mill village mamas and daddies not only encouraged this notionthey hammered it home. Many kids ate supper at the family table in a cloud of rancor and outrage caused by their fulminating parents reaction to their latest mill insult. They consumed resentment and anger toward the mill company with their butterbeans and cornbread.

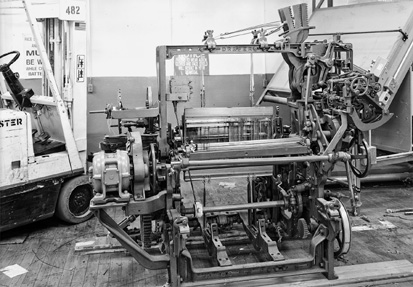

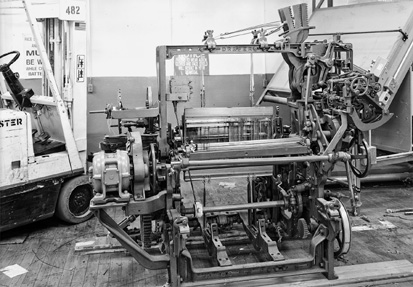

By the early 1900s, West Point Manufacturing owned five Alabama mill villages in the Chattahoochee Valley. Each of the villages was built around its own mill, starting with Lanett at the northern end, and then, in descending order, Shawmut, Langdale, Fairfax, and Riverdale. Inside the Riverdale Cotton Mill at the intersection of Middle and Lower Streets, Valley, Alabama, courtesy of the Collections of the Library of Congress.