VI. THE INFLUENCE OF THE RISE OF THE OTTOMAN TURKS UPON THE ROUTES OF ORIENTAL TRADE.

By ALBERT H. LYBYER,

Professor in the University of Illinois.

[Reprinted from The English Historical Review , October 1915]

The English

Historical Review

NO. CXX.OCTOBER 1915

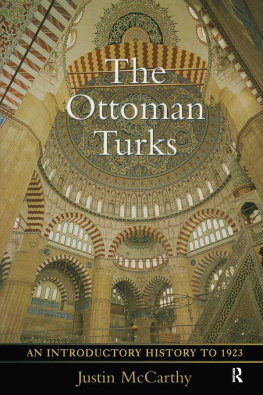

The Ottoman Turks and the Routes of Oriental Trade

W ITHIN a period of a little more than two hundred years, from the close of the thirteenth century to the second decade of the sixteenth, the rising power of the Ottoman Turks extended the area of its political control until its holdings stretched north and south across the Levant from the Russian steppes to the Sudanese desert. The Turkish lands thus came to intercept all the great routes which in ancient and medieval times had borne the trade between East and West. Near the time when the Turkish control became complete, a new way was discovered, passing around Africa; and within a few years the larger part of the through trade between Europe and Asia had deserted the Levantine routes and begun to follow that round the Cape of Good Hope. The causes of this diversion of trade have not been fully agreed upon. No specific investigation of the subject appears to have been made. A glance through works which, being mainly concerned with other subjects, have alluded to the shifting of the routes of oriental trade about the year 1500, shows that two incompatible views are prevalent. One of these holds in general that the advance of the Ottoman power gradually blocked the ancient trade-routes and forced a series of attempts to discover new routes; after these attempts had succeeded, the Turks continued to obstruct the old routes and compelled the use of the new. The other view finds little or no connexion between the growth of the Turkish power and the causes of the great discoveries: a set of motives quite independent of the rise of the Turks led men like Henry of Portugal and Christopher Columbus to explore the unknown world; and when the new route to India had been established it was found to possess an essential superiority for trade, which gave it pre-eminence until in the nineteenth century the balance was again turned by the introduction of steam navigation and the opening of the Suez Canal. The evidence appears to be overwhelmingly in favour of the second of these views. In the present article, however, without arguing the question directly, it is proposed to survey the course of oriental trade from the close of the great Crusades until the eighteenth century, so as to show the influence of the Ottoman Turks as it emerged historically.

The medieval trade-routes between western Europe and eastern and southern Asia fall into two groups: the northern, which passed mainly by land, and the southern, which passed mainly by sea. The former communicated with central Asia, China, and India through the Black Sea and Asia Minor, the latter through Syria and Egypt. Each group had branches which entered Asia near Aleppo and diverged in the direction of Tabriz and Bagdad. On all routes there were what in America are compendiously termed long hauls and short hauls; that is to say, wares which travelled most of the way, as Western silver and coral and Eastern silk and spice, and wares which travelled only part of the way, as sugar, cotton, and Arabian gums. It was possible, also, for merchants who dealt in goods of the former class to travel the whole road or to go only part of it and sell or exchange their commodities, which would be carried on by other hands. For most goods the southern routes, especially that by the Red Sea, were cheaper, because they ran mostly by sea;

At the beginning of the fourteenth century five routes were most in use: the land road through Tana from the mouth of the Don north of the Caspian Sea to China; the way through Trebizond to Tabriz and central Asia; the two roads from Lajazzo (Ayas) at the head of the Gulf of Alexandretta, one by Tabriz, the other by Bagdad and the Persian Gulf to India and beyond; and finally the route by the Nile, Kosseir, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean to southern and eastern Asia. but who, as well as their subjects, derived great profit from a large trade between West and East. Christian cities, especially Venice, Genoa, and Barcelona, traded regularly at Alexandria.

The popes never forgave the Mamelukes for expelling Western Christians from the Holy Land,

In 1356 the Ottoman Turks established themselves on both sides of the Dardanelles, and, though they had little shipping they were able to exercise some influence on the fraction of oriental trade which still passed through the Black Sea. They also gradually incorporated the other Turkish principalities in Asia Minor, and with them took over their trade agreement with Genoa and Venice and their rights to tribute from certain of the Aegean Islands. The Turks took no part in this process, though they suffered from it, both in Timurs time and afterwards.

Venice had by now beaten Genoa decisively, and there ensued a century of comparative stability in the oriental trade. Pearls, silk, pepper, ginger, nutmegs, mace, cinnamon, and cloves were steadily exchanged in Syria and Egypt against gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, coral, and the like. Supply and demand have their effect even upon monopoly prices.

By about 1450, when the Turks had recovered most of their losses at the hands of Timur, trade relations were regularly conducted by caravan between Brusa, the first Ottoman capital, and Aleppo and Tabriz.

The commercial policy of the Turks, now well established, was not at all one of hostility to trade. They sought indeed to exclude foreigners from their internal commerce, as well as from the conduct of through trade while crossing their lands.

After his conquest of Trebizond Mohammed II came into conflict with Venice in 1464 and took some of her Levantine territory. War followed for nine years, in the course of which a new route of Eastern trade was temporarily opened.

In the war of Bayezid II with the sultan of Egypt, during the years 1485 to 1491, caused by the latters giving asylum to the formers brother, Prince Jem, the Turkish troops were thoroughly defeated. The course of oriental trade through Syria and Egypt was not in the least molested by the Turks before the year 1516. Along the northern routes, whose outlets were in their hands, they made no effort to stop the flow of wares. In times of peace and order in Persia many caravans passed east and west, exchanging wares from the Aegean Sea even to the far interior of Asia. There continued also a regular movement north and south to Aleppo, and thence to Bagdad and Mecca and the East. If the Turks had hindered oriental trade, they had checked it but slightly. During their frequent wars commerce was more or less disturbed; but the wars usually ended in an increase of territory which furnished a wider commercial opportunity.

Through Egypt and Syria, although disputes about the succession to the Mameluke throne, occasional visitations of the plague, and quarrels between natives and Europeans caused the volume of trade to fluctuate, the old flow of oriental wares was maintained unbroken down to 1502.

After 1502, then, the carrying of spices from India to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf was interfered with by the Portuguese. Nevertheless, besides the diminished amount of spices which was taken by the Venetians and others from Aleppo and Alexandria for European consumption, goods of the same class required in Arabia, Persia, Turkey, and North Africa continued to travel by the old routes. In fact this trade appears never to have ceased. The real revolution was already accomplished. The beginning of the economic decay of the Levant and of the decline of Venice and the Mediterranean trading cities dates, not from the Turkish conquest of Egypt in 1517, but, if its causes be not traced even earlier, from the doubling of the Cape of Good Hope by the Portuguese in 1498.