Quarterly Essay is published four times a

year by Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

ISSN 1444-884X

Subscriptions (4 issues): $34.95 a year

within Australia incl. GST (Institutional

subs. $40). Outside Australia $70. Payment

may be made by Mastercard,Visa or Bankcard, or

by cheque made out to

Schwartz Publishing. Payment includes

postage and handling.

Correspondence and subscriptions should

be addressed to the Editor at:

Schwartz Publishing

Level 3, 167 Collins St

Melbourne VIC 3000

Australia

Phone: 61 3 9654 2000

Fax: 61 3 9654 2290

Email: quarterlyessay@blackincbooks.com

Publisher: Morry Schwartz

Editor: Peter Craven

Management & Advertising: Silvia Kwon

In-house Editor: Chris Feik

Marketing & Publicity: Angela Crocombe

Design: Guy Mirabella

Printer: Griffin Press Pty Ltd

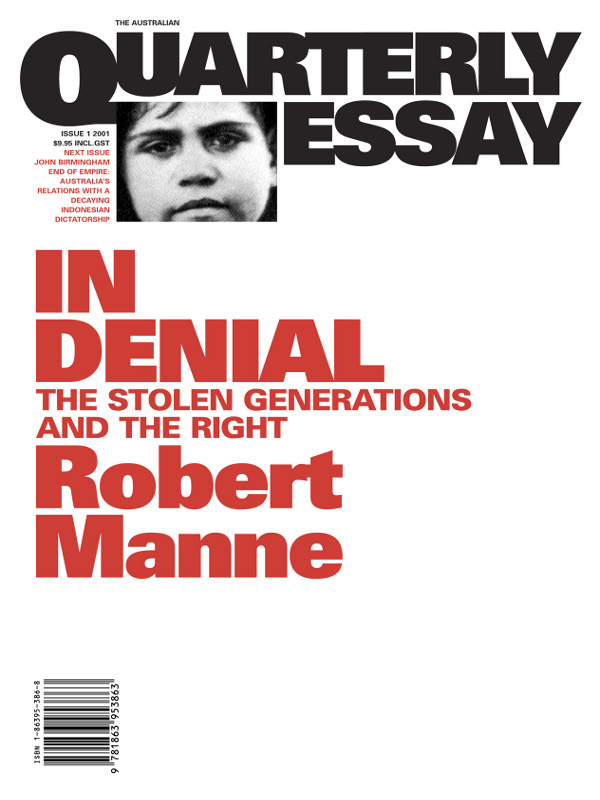

Robert Mannes In Denial: The Stolen Generation and the Right, the first essay in the Quarterly Essay series, is an attempt to come to terms with the fact that a group of right-wing commentators (centred in the first instance around Mannes old magazine Quadrant under the editorship of Paddy McGuinness) has effectively railroaded the national awareness of how large numbers of Aboriginal children were separated from their families in the period between 1910 and 1970. As Manne presents it, this is a story of how a failure of sympathy, a hardening of the imaginative arteries, is abetted at every point by a form of wishful thinking about the past and compounded by a woefully impoverished sense of evidence. It is the story of how a small group of people have been responsible for minimising or confusing the general apprehension of the great pain inflicted on thousands of Aboriginals, no doubt often enough by people of good will.

Inga Clendinnen once described Robert Manne as a writer of ravishingly cool analyses but In Denial is not simply cool. It exhibits all of Mannes dispassion but it is also a long polemical essay which not only chops up the opinion men of the right like firewood but which does so in sorrow and in anger.

It is a tightly argued case against McGuinness and the Quadrant school of stolen generations deniers that is also a terse and brilliant account of how government policies towards the Aborigines blighted the lives of myriads of harried, dispossessed people, who were left bereft in so many cases of that most elementary of things, the bond between mother and child.

Manne is sword-point sharp in tracing the evolution of the policies that held sway, but he never loses sight of the grief-torn faces. Of Aboriginal mothers fleeing the bush at the mere sight of a policemans helmet, of young girls strapped for trying to touch a family hand through an institutional fence, of a young boy sent to a series of Homes and prisons (in the 1960s) because he pinched a bicycle from a high school. And of how that same boy, after years in prison for petty offences comes to kill first his sisters boyfriend and then himself. No reader of In Denial will soon forget what Malcolm made of the biblical text, if thine eye offend thee.

In Denial is an impassioned defence of the vision of sorrow and pity which the Bringing them home report bequeathed to the nation, but its at the same time not an unqualified endorsement of its detail. Manne is adamant that Bringing them home had the great virtue of creating an atmosphere of confidence for the victims themselves. Compared to this the flaws of the report are minor flaws indeed.

And he makes short shrift of the authorities who opposed the report: Ron Brunton, the anthropologist who has lent his voice to the interests of the mining companies; Colin Macleod, the one-time junior patrol man; and Reginald Marsh, whose theory of Aboriginal removal Manne sees as a myth and a dangerous one.

The gravest judgment this essay offers is of the opinions expressed by Peter Howson, a former Minister for Aboriginal Affairs.

In Denial is a demolition job on the historical demolitionists who have attempted to minimise, to effectively deny, the reality of the stolen generations. When Robert Manne was ousted as editor of Quadrant, the main objection of the prime mover, the poet Les Murray, was the account of the Aboriginal question given by Manne and his close associate Raimond Gaita (who articulated the shame/guilt distinction with maximum clarity).

His successor P. P. McGuinness, one-time man of the left and Sydney MorningHerald columnist, promised a new line, devoid of sentimentality and offering a genuine debate. Manne sees McGuinness as the central strategist in the war on the stolen generations and in his account of McGuinnesss writings he provides what looks like a devastating critique of his successors denials.

Robert Mannes central contention is that the deniers of the stolen generations, the nay-sayers of the Right, created an atmosphere of disbelief in the idea that many Aboriginal children had been treated unjustly. In Denial is a comprehensive rebuttal of the group of influential columnists that includes Piers Akerman, Frank Devine, Christopher Pearson, Michael Duffy and Andrew Bolt. Indeed In Denial begins very topically with an account of Bolts supposed exposure of Lowitja ODonoghue in late February of this year.

Many people believe that Andrew Bolts article was a dangerous beat-up. To the small, highly influential group of right-wing columnistsfuelled with the Quadrant evidence Manne contests so convincinglyBringing themhome was itself a beat-up that appealed to the moral vanity of a left-wing intelligentsia who constituted a moral mafia and who wanted to decry the legacy of Australian history.

One of the strengths of Robert Mannes In Denial is the persuasiveness with which he suggests that John Howards government (the government which has refused to apologise to the Aborigines) was in fact collusive with the right-wing Quadrant-led campaign against the perspectives that derive from Bringing them home.This is highlighted by the account Manne gives of the governments defence in the CubilloGunner case (the stolen generations test case) and the way it was conducted by Douglas Meagher QC.

Manne does not deny that any government would have conducted a robust defence but he suggests that the Meagher case for the Howard government exceeded normal bounds. In a brilliant forensic move Manne highlights the fact that Meagher saw fit to address a Quadrant seminar on the subject of the Aborigines and shows how the speech he gave misconstrued the evidence about the Harold Blair project in 1960s Melbourne. He relates this in turn to Meaghers father, Ray Meagher, the State Minister for Aboriginal affairs.