Page List

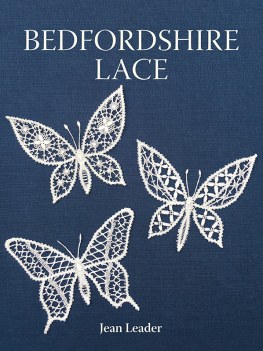

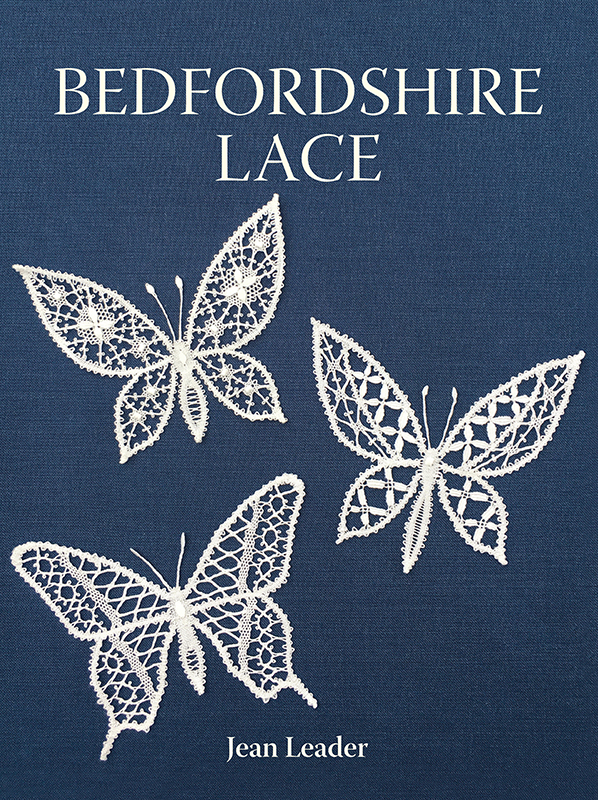

BEDFORDSHIRE

LACE

Handkerchief edging worked by the author from a draft in The Cecil Higgins Art Gallery & Museum, Bedford.

BEDFORDSHIRE

LACE

Jean Leader

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Jean Leader 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 819 1

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my husband David for all his support and in particular for his help in re-drawing many of my diagrams, my friend Gilian Dye for reading my first drafts and making useful suggestions for improvement, and The Lace Guild for a bursary to study the Rose Family Sample Book. Thanks are also due to the lace teachers and authors who have inspired and encouraged me Barbara Underwood in particular, but also Mo Gibbs, Pamela Nottingham, Pamela Robinson and Margaret Turner, whose selection of patterns published by Ruth Bean first made me fall in love with Bedfordshire lace.

INTRODUCTION

B edfordshire lace developed in the mid-nineteenth century, partly in response to the fashion trends of the time that favoured bolder laces. Together with similar bobbin laces from other parts of Europe, it was also as a reaction to the ever-increasing threat of competition from machine-made lace. Bedfordshire is one of the three counties that make up the East Midlands lacemaking area of England, the other two being Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire, but despite its name this lace was made in all three counties and neighbouring villages. Bobbin lace had been made in this area since the late sixteenth century where it was organized as a cottage industry, with the lacemakers working in their own homes using patterns and thread supplied by lace dealers. Periodically the dealers would collect the finished lace and arrange for its sale.

The success of the industry, and the style of lace made depended very much on whatever was currently fashionable. The beginning of the nineteenth century had been a successful time for the East Midlands industry with fashions favouring the relatively simple Bucks Point laces with net grounds and limited decoration that were being made there. This was also a time when the Napoleonic Wars limited the import of European laces. However, this success was not to last in nearby Nottingham machines were being developed which could reproduce the bobbin-made net perfectly. By the 1850s lace machines had developed at such a pace that they were able to produce lace with both net ground and decoration that was difficult to distinguish from hand-made lace. In order to survive, the hand-made lace industry needed something new that could not be reproduced by machine and was also fashionable. The answer was a lace where the pattern motifs were joined by bars of plaited thread, rather than a net ground; this was initially called Bedfordshire Maltese. The use of Maltese in the name was no doubt to benefit from the publicity that this style of lace from Malta (itself based on old Genoese lace) had received when exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The same style of lace was also made at the lacemaking centres of Mirecourt and Le Puy in France and in a similar marketing ploy this was given the name Cluny after the Muse Cluny in Paris, where seventeenth-century Genoese lace was exhibited. What all these laces have in common is that the designs include plaited bars, often decorated with picots; small woven blocks known as tallies; trails worked in cloth stitch; other design elements in cloth stitch or half stitch, sometimes embellished with overlaid or raised tallies.

How the lacemakers learnt to make this new style of lace does not seem to have been recorded. Were they simply given a sample with the new pattern and left to work it out for themselves? Or did the lace dealers send someone to show them what to do? However it happened the lace was soon being produced in quantity. Much of this lace was insertions and edgings there is a sample book dating from the 1860s that belonged to the Rose family, lace dealers from Paulerspury in Northamptonshire, which contains over 600 unique patterns ranging in width from under 2cm to over 5cm (this book is now in the care of the Lace Guild Museum). Larger items such as collars, cuffs, head pieces and wide flounces, often with elaborate floral designs, were also made. Some of these patterns are known to have come from local designers of whom Thomas Lester is probably the best known, but the designers of the many insertions and edgings are anonymous.

Unfortunately for the lacemakers, the machine-made lace industry did not stand still and before long even this new style of lace could be produced by machine. By 1900 most of the hand-made lace industry in England had disappeared, and it is only the interest and dedication of a few individuals that has ensured knowledge of lacemaking techniques and patterns has been preserved for the benefit of all the lacemakers who now enjoy bobbin lacemaking as a fascinating hobby.

A selection of Bedfordshire lace edgings.

CHAPTER 1

EQUIPMENT, MATERIALS

AND GETTING STARTED

A ll bobbin laces are made with multiple threads, each wound on to a separate bobbin, and are worked on a pattern, known as a pricking, attached to a firm pillow. Stitches are worked with two pairs of bobbins (four threads), and are held in place as they are made with pins pushed through the pricking into the pillow. When the lace is finished it is released from the pillow by removing the pins. The style of the pillow and bobbins used can vary between lacemaking areas, while the size of the pins and the thread used will depend on the style of the lace being made.

The same basic stitch movements are used in all bobbin laces, but how the stitches are arranged varies from one type of bobbin lace to another. Bedfordshire is one of the continuous bobbin laces; that is, one that starts with all the threads needed for the full width of the lace. These threads remain in use throughout and the lace is worked in one direction.