THE OHIO RIVER VALLEY SERIES

Rita Kohn

Series Editor

American Grit

A Womans Letters from the Ohio frontier

Edited by

Emily Foster

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2002 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2009

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

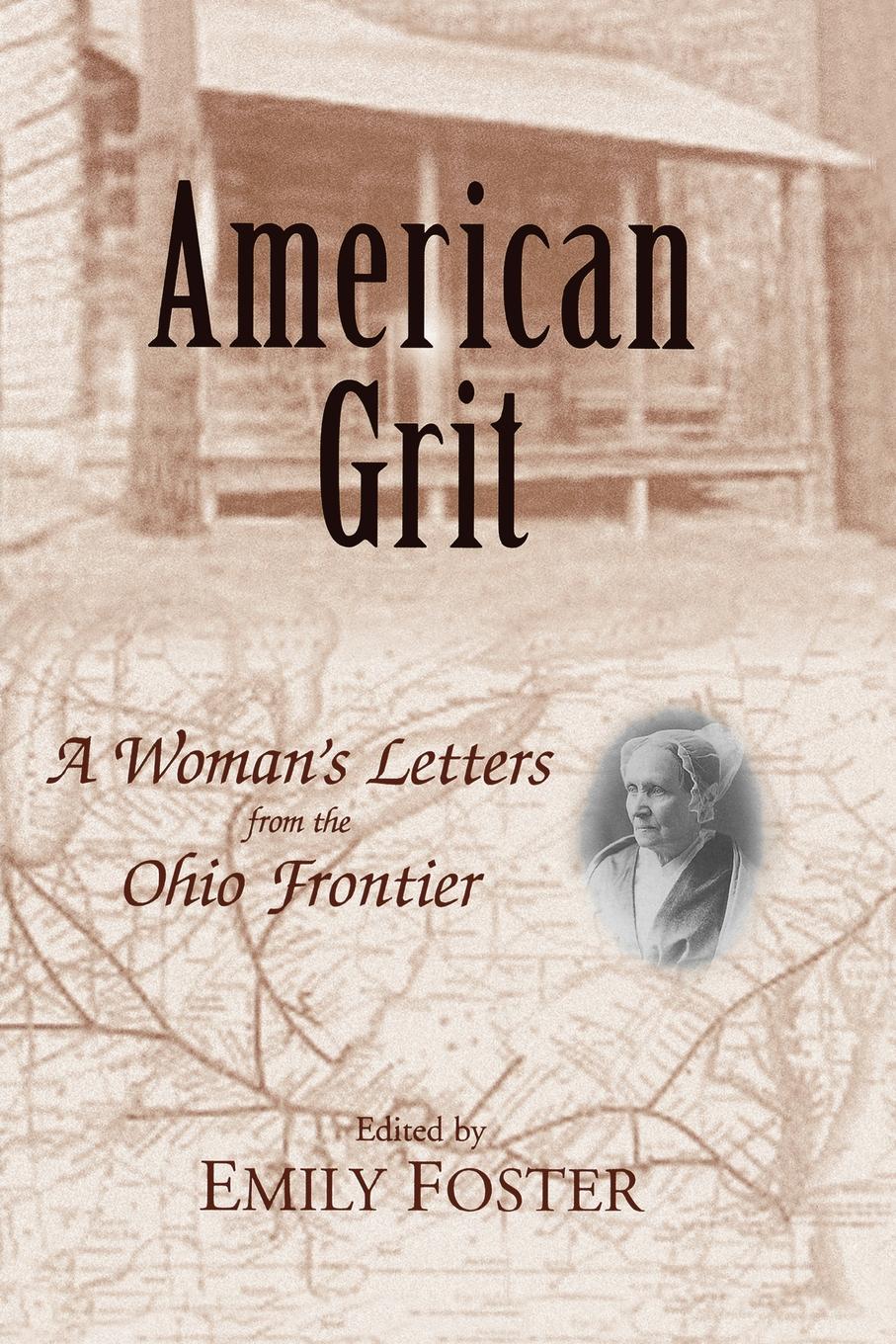

Frontispiece: Anna Briggs Bentley, 17961890. Courtesy Virginia Niles Taylor.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-9267-3 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

Contents

Series Foreword

The Ohio River Valley Series, conceived and published by the University Press of Kentucky, is an ongoing series of books that examine and illuminate the Ohio River and its tributaries, the lands drained by these streams, and the peoples who made this fertile and desirable area their place of residence, of refuge, of commerce and industry, of cultural development and, ultimately, of engagement with American democracy. In doing this, the series builds upon an earlier project, Always a River: The Ohio River and the American Experience, which was sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the humanities councils of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, with a mix of private and public organizations.

Each books story is told through men and women acting within their particular time and place. Each directs attention to the place of the Ohio River in the context of the larger American story and reveals the rich resources for the history of the Ohio River and of the nation afforded by records, papers, artifacts, works of art and oral stories preserved by families and institutions. Each traces the impact the river and the land have had on individuals and cultures and, conversely, the changes these individuals and cultures have wrought on the valley with the passage of years.

The letters of Anna Bentley and her family provide drama and insights beyond fictionalized sagas. Emily Fosters The Ohio Frontier, her best-selling first book with the University Press of Kentucky, proved regional history can be a page turner. Now, American Grit: A Womans Letters from the Ohio Frontier, as a story of the Quaker religion, its evolution during the nineteenth century and its impact on the emerging nations social, political, and feminist issues, equally offers a unique understanding of pioneer daily life in eastern Ohio.

Ordinary people engaged in ordinary living makes for extraordinary reading, be it with a meticulous listing of items lovingly received by a frontier family destitute of clothing and household goods such as sewing needles and tablecloths, or with the fulsome itinerary of goings and comings where distant neighbors are creating a new social order. We experience the myriad illnesses and homemade remedies including medicinals and herbals that we now are revisiting as part of holistic health care. In direct relation to the nations evolving economy we witness the downsizing of families from that of Anna Bentleys generation to that of her children and grandchildren. We observe values and relationships in transformation.

But most important, Anna Bentleys story flies in the face of the stereotypical presentation of the wife being wrenched from her comfortable eastern home by a husband bent on conquering the frontier. Rather, we witness a partnership where suffering hardships is gender equal. To survive, Anna clearly understood and advanced the need to find arable land. Hearing Annas views is refreshing and revelatory. Foster is not immodest in stating that this is about as honest a report as were likely to getno artifice, no posturingits straight from the heart. Human beings emerge, warts and all.

While reading someone elses mail may seem voyeuristic, doing so is perfectly acceptable nearly two hundred years later. Wrestling and finally wresting sustenance from a place not initially suited to be farmed in the European tradition becomes a repeated story across this nation. That the Maryland soil was depleted so early proves how out of sync the initial Atlantic seaboard settlers were with land use. We come to appreciate the understandings the Nanticokes had, which the Europeans lacked. While Foster has done extensive research to verify and provide context, she skillfully allows the original words to convey their narrative. Ultimately, we see Anna, the Ohio frontierswoman who begged goods and money from her Maryland family, become the matriarch-giver of goods and money to her own children who move ever westward. Here we have a universal story of living on the fringe of poverty. Letter after letter, we experience history unfolding, consequently providing context for pressing contemporary issues.

Rita Kohn

Series Editor

Acknowledgments

Since I first looked at the collection of Anna Briggs Bentleys letters housed in the Maryland Historical Society archives in 1998, many people have helped me. Some were hardly aware they were assisting a research project, but they helped nonetheless. I owe gratitude to more people than I can name.

To begin at the moment I saw Anna Bentleys letters, I would like to thank Jennifer Bryan, Mary Herbert, and the other staff at the Maryland Historical Society for their patience, expertise, and good will. The same might be said of staff at other archives, who without exception helped make my visits both efficient and fruitful. Among them, Lauren Brown at the University of Maryland Libraries; Frances Pollard of the Virginia Historical Society archives; Richard Dinsmore of the Ritter Library, Baldwin-Wallace College; Fran Parker, Jean Snyder, and Lee Halper of the Sandy Spring Museum; Daisy Hagan-Bolen at the Columbus Metropolitan Library; and staff at the Ohio Historical Society archives and the Salem Public Library. I would also like to note the friendly assistance of Rebecca Hankins of the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

Member of the Association of

Member of the Association of