Incarcerated Mothers

Oppression and Resistance

Incarcerated Mothers

Oppression and Resistance

edited by

Gordana Eljdupovic

and

Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich

DEMETER PRESS, BRADFORD, ONTARIO

Copyright 2013 Demeter Press

Individual copyright to their work is retained by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by:

Demeter Press

140 Holland Street West

P. O. Box 13022

Bradford, on L3Z 2Y5

Tel: (905) 775-9089

Email: info@demeterpress.org

Website: www.demeterpress.org

Demeter Press logo based on Skulptur Demeter by Maria-Luise Bodirsky

< www.keramik-atelier.bodirsky.edu >

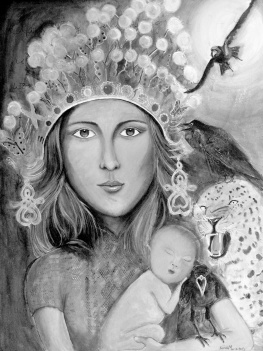

Cover Artwork: Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich, Incarcerated Mother, 2012,

acrylic on canvas.

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Printed and Bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Incarcerated mothers : oppression and resistance / Gordana

Eljdupovic and Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich, editors.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-927335-03-1

1. MothersCanada. 2. Women prisonersCanada.

3. Women prisonersFamily relationshipsCanada.

4. MotherhoodSocial aspectsCanada. 5. Mothers.

6. Women prisoners. 7. Women prisonersFamily relationships.

I. Eljdupovic, Gordana, 1960 II. Bromwich, Rebecca

HQ759.I54 2013 306.8743086927 C2013-900727-X

To my mother Ljubinka, with love and gratitude.

Gordana

With love to my mother, Beverley, for many reasons,

and most of all because you taught me that mothering is a political act.

Rebecca

Unless otherwise indicated, all authors views are theirs alone and do not reflect official statements of any, body, agency or group of any kind.

Table of Contents

Gordana Eljdupovic and Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich

Dena Derkzen and Kelly Taylor (Canada)

Gordana Eljdupovic, Terry Mitchell, Lori Curtis,

Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich, Alison Granger-Brown,

Courtney Arseneau and Brooke Fry (Canada)

Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich (Canada)

Martine Herzog-Evans (France)

Deseriee A. Kennedy ( USA )

Upneet Lalli (India)

Manuela P. da Cunha and Rafaela Granja (Portugal)

Ruth McCausland and Eileen Baldry (Australia)

Alison with Brenda, Sarah, Martina, Tanya, Devon, Jennifer,

Betty, Renee, Patricia, Mo, Kelly and Linnea (Canada)

Olivia Scobie and Amber Gazso (Canada)

Christine A. Walsh and Meredith Crough (Canada)

Gordana Eljdupovic (Canada)

Karen Shain, Lauren Liu and Sarah DeWath ( USA )

Ruth Elwood Martin, Joshua Lau and Amy Salmon (Canada)

Danielle Poe ( USA )

Julie Herrnkind

Photo: Patricia Block

I was 30 years old and three months pregnant when I received a sentence of two years. The program to keep incarcerated mothers and babies together had been suspended. My daughters name is Amber Joy and she is almost three years old now. The day at the hospital when I had to kiss my baby goodbye was the most hopeless, miserable, and empty experience of my life. I often asked why was she being punished for something that I did?

Patricia Block

Introduction

GORDANA ELJDUPOVIC AND REBECCA JAREMKO BROMWICH

I N THE WINTER OF 2012, headlines broke across the United States with stories of incarcerated women who had successfully sued U.S . prisons after having been forced to give birth alone, with no assistance. These situations gave rise to public shock. It is surprising and uncomfortable for the general public to think about incarcerated people being women. It is even more discomfiting to consider that a large proportion of incarcerated women are mothers.

This book is about the lives, needs and rights of mothers who are, or have been, incarcerated. Mothering and incarceration are generally perceived as being contradictory. Mothering is distinctly or primarily a female phenomenon, while incarceration is primarily, statistically and stereotypically, male. Although there are men who engage in mother-work, such work is oftenif not invariably and cross-culturallyunderstood to fall within the womens domain. Similarly, it is consistent across countries that the number of incarcerated males, by far exceeds the number of women. As a result, incarcerated mothers are doubly stigmatized or double odd. They are where most of the women are not or should not be. They are in jail, like men. At the same time, incarcerated mothers are not doing what social expectations dictate that good mothers should do; they are not providing daily care to their children. Rather, they are separated from their children, leaving them in the care of someone else, often a stranger.

In this introduction, we review considerations feminist scholars have raised about motherhood that particularly pertain to issues addressed in this collection of essays. We then discuss and review perspectives on female crime and incarceration with a specific focus on incarcerated mothers.

Finally, we present the essays in this collection and identify what this book does and does not address, in so doing we provide suggestions for future inquiries.

MOTHERHOOD AND MOTHERING

Motherhood has been a central and inseparable area of scholarly feminist inquiry over a number of decades. It would be difficult to find feminist analysis that does not in some way examine this domain of womens lives. Furthermore, some feminist scholars have developed and significantly advanced this particular area of inquiry providing specific theories of motherhood. The theoretical underpinnings for this book are primarily drawn from the work of motherhood theorists Sara Ruddick and Andrea OReilly. Ruddick, who died in March of 2011, was a leader in advancing the notion that motherhood carries with it a set of thought practices that can be of tremendous benefit in social activism and towards global peace making. OReilly, a Canadian academic, developed a mothers movement of scholarship and action that further expanded and brought into being Ruddicks vision.

Feminist scholars and activists have critiqued the traditional characterization of motherhood as a natural and ideal role for women. As is the case with feminist scholarship in general, initial and dominant discussions of issues pertaining to this area were based on patriarchal families in the western world. Feminists showed that the cluster of activities and biological functions that presumably define mothering is not inevitably female, although it is understood as a natural outcome of what until recently has represented the only legitimate family structure: the patriarchal nuclear family. This family structure is characterized by biological parents being married, with the mother assuming the role of a nurturer, and the father, the role of the provider.

By ascribing the public sphere to men and the private one to women, a power imbalance between genders has been created and legitimized, placing women in a disadvantaged position. As Ruddick reminds us, the hand that rocks the cradle has certainly not ruled the world (36). An extremely powerful mechanism of maintaining these social arrangements involves socializing women and men into gender specific roles. This mechanism leads women to want to mother, to want to have a family and nurture, and to strive for the roles as assigned to them (Polatnick). In other words, women choose to do the unpaid labour and take care of others. They remain disengaged from political and social domains, which renders them with minimal decision making power and economically dependent. Moreover and equally important is the fact that the role of a nurturer is characterized by significant emotional demands. As Adrienne Rich and many other scholars have shown based on explorations of their own mothering, demands for unconditional, on-going, selfless and endless love, care and affection for children are unattainable and exhausting for the mother. Further, it is socially unacceptable for the mother to acknowledge that she may feel tired, frustrated or yearn for something else. For those reasons, a mother may feel isolated, ashamed, incompetent and incapable of responding to her calling.