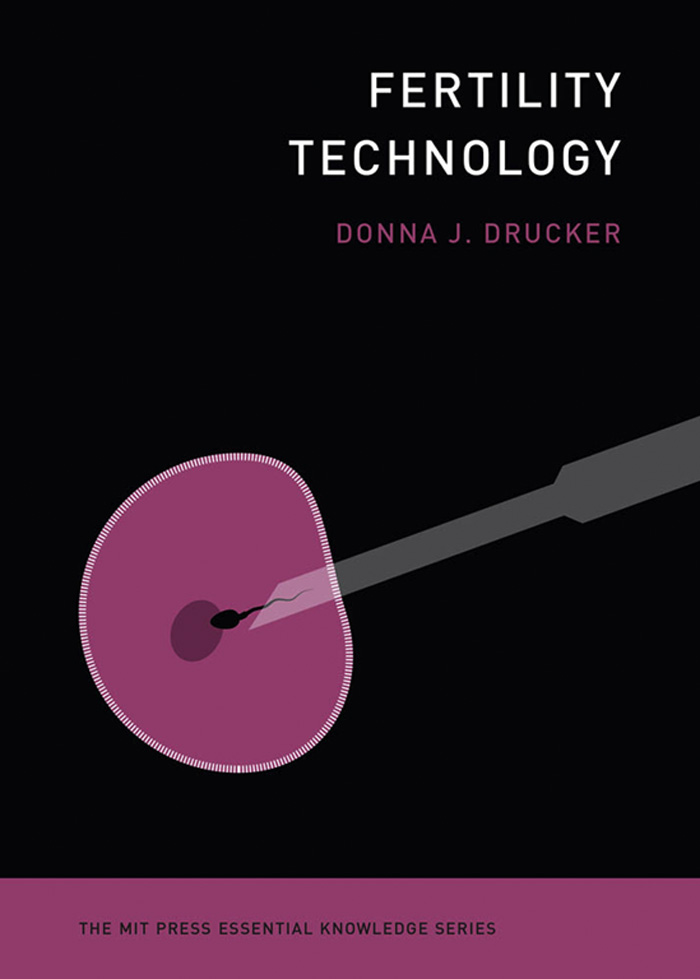

Fertility Technology

The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series

A complete list of books in this series can be found online at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/series/mit-press-essential-knowledge-series.

Fertility Technology

Donna J. Drucker

The MIT Press|Cambridge, Massachusetts|London, England

2023 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Chaparral Pro by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Drucker, Donna J., author.

Title: Fertility technology / Donna J. Drucker.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2023] | Series: The MIT Press essential knowledge series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022011344 (print) | LCCN 2022011345 (ebook) | ISBN 9780262544696 (paperback) | ISBN 9780262372329 (epub) | ISBN 9780262372336 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Human reproductive technology. | Fertility.

Classification: LCC RG133.5 .D78 2023 (print) | LCC RG133.5 (ebook) | DDC 618.1/7806dc23/eng/20220629

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022011344

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022011345

10987654321

d_r0

Contents

Series Foreword

The MIT Press Essential Knowledge series offers accessible, concise, beautifully produced pocket-size books on topics of current interest. Written by leading thinkers, the books in this series deliver expert overviews of subjects that range from the cultural and the historical to the scientific and the technical.

In todays era of instant information gratification, we have ready access to opinions, rationalizations, and superficial descriptions. Much harder to come by is the foundational knowledge that informs a principled understanding of the world. Essential Knowledge books fill that need. Synthesizing specialized subject matter for nonspecialists and engaging critical topics through fundamentals, each of these compact volumes offers readers a point of access to complex ideas.

Preface

This book, like others in the field of reproductive studies, must balance the relevance of women and men as categories of personhood with specific historical meaning and the necessary inclusion of transgender and non-binary individuals, whose ability to become pregnant or to impregnate someone else may not correlate to their gender identity. I use gendered terms when needed to discuss particular experiences of self-identified women and men in the past and use gender-neutral terms as much as possible.

This book is not a guide to choosing a fertility method. Please consult a health care practitioner for advice.

1

Technology for Fertility

In the late 1850s, a twenty-eight-year-old woman approached the Womans Hospital in New York City. She had been married for nine years and was willing to try anything to conceive a child. Though Sims was unsuccessfulthis was the only pregnancy out of his fifty-five attempts at using the syringe-tube combination, and it did not result in a live birthhis description of using medical tools for artificial insemination inspired other medical professionals to try using technologies to assist patients with their quest for a child.

This book is a history and analysis of the following principal types of fertility technologies from the 1860s to the present: (1) devices and techniques related to artificial insemination (AI); (2) diagnostic tools and surgical techniques, particularly insufflation and salpingogram apparatuses; (3) ovulation timing in a monthly cycle; (4) in vitro fertilization (IVF) and its associated and subsequent developments; and (5) sperm, egg, and embryo freezing. This book is organized chronologically according to the first recorded use of each technology, and then traces the offshoots of the original technology into the present. It focuses on each technologys development, dispersion, and use in humans but includes use for animals where relevant. It argues that fertility technologies are not neutraltheir innovation and use have both reflected and shaped how people think about reproduction, family, race, and kinship from the mid-nineteenth century through the present. As Katharine Dow writes, How we reproduce seems to say something about who we are and who we want to be and because of a sense that future generations are the product of parents reproductive decision-making.

Fertility technologies are not neutral.

It is important to note that the study of fertility technology and the study of fertility and infertility are not the same. The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, uses a medical definition of infertility: infertility is a disease of the male or female reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after twelve months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. Depending on the context and situation, infertility can be a disease, a story, a disorder, a chronic illness, a form of suffering, a disabilityor some combination of the above. It eludes a singular definition.

There are many nuances in sociocultural understandings of infertility that are harder to find in the historical record. For example, records may not distinguish between primary infertility (no live births) and secondary infertility (aka subfertility, not more than one birth without assisted reproductive technologies [ARTs]). Women not seeking pregnancy may be infertile without knowing itor it not mattering to them. Records created by elites, however (and especially elites in the medical profession), privilege the construction of fertility or infertility as a medical condition. If infertility is categorizable as a medical condition, then it follows that it has (or could have) a medical treatment, and many physicians followed this line of thinking as they sought technological and surgical cures for their patients. This book traces advances and experiments in medical practice, which often take place in the most industrialized countries. It also provides a broader picture of the reception of these technologies around the world, and of how child-seekers used technologies on their own terms to try and manifest pregnancies, births, and families according to their own vision.

The study of fertility technology and the study of fertility and infertility are not the same.

This chapter introduces the following chapters and the key concepts of the book, and it considers why people seek a technological fix for fertility problems in the first place. It is no coincidence that physicians and patients started to look for technological assistance in the mid-nineteenth century, when industrial capitalism and colonialism were at worldwide peaks of influence. The world was awash in new technologies, to put it mildly, and the absence of wanted pregnancy was yet another medical problem that could potentially be solved with the application of appropriate technology.

The second chapter traces the development of six different technologies in use from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, gynecologists used the relatively simple combination of a cannula and syringe to place fresh semen as deep as they could into the vaginaand past the cervix into the uterus if possible. In the 1910s and 1920s, physicians using this technique added a stem pessary or cervical cap to the process after the seminal injection to hold the fluid in place. Likewise in this era, physicians sometimes prescribed hormonal supplements, and they began to use insufflation apparatuses or salpingograms to check for and to remove blockages in the fallopian tubes, sometimes followed with AI. However, the ideal timing for the injection of semen was guesswork until Dr. Kyusaku Ogino (18821975) and Dr. Hermann H. Knaus (18921970) confirmed the timing of ovulation in a womans monthly cycle. Once the timing of egg maturation could (roughly) be established, ovulation timing trackers could be either combined with insufflation and AI or used on their own, particularly for married Roman Catholic couples.

Next page