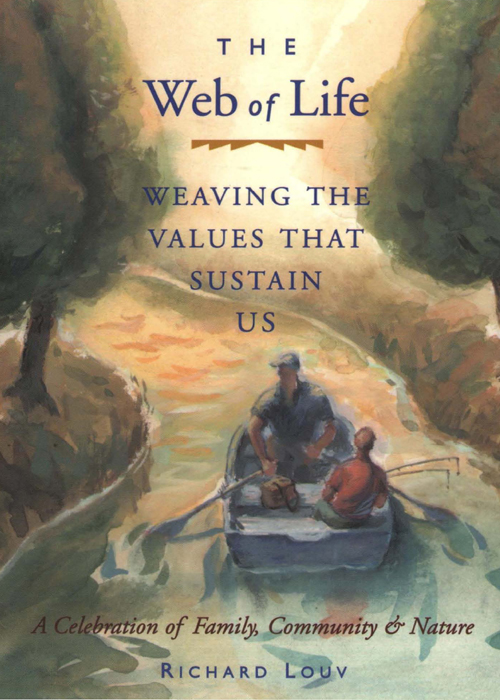

Books by Richard Louv

The Web of Life

FatherLove

101 Things You Can Do For Our Children's Future Childhood's Future America II

Copyright 1996 by Richard Louv.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Conari Press, 2550 Ninth Street, Suite 101, Berkeley, CA 94710.

Cover Design: Nita Ybarra Design

Conari Press books are distributed by Publishers Group West

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Louv, Richard.

The web of life : weaving the values that sustain us / Richard Louv.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-57324-036-2 (hardcover)

1. Meditations. I. Title

BL624.2.L68 1996

814'.54-dc20

95-51847

Printed in the United States of America on recycled paper.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Man did not weave the web of life. He is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web he does to himself.

Chief Seattle

The Web of Life

To the memory of lucy Hollembeak

Weaving

VISUALIZE THE WEB OF YOUR LIFE, intricate and mysterious. The web is there for us all; all of us are weavers. For children, one strand is made of parents, another is the school system, another is the work place and how it treats parents, another is the neighborhood. But all of us, no matter how young or old, need a web of family, friendship, community, nature, time, and spirit.

In our culture, this weaving is a kind of lost art, awaiting rediscovery.

Consider the strands. In current times, the web has become our most powerful ecological image. Scientists no longer talk of the food chain, but of the food web. Each organism's life cycle is intertwined with the lives of all other organisms. But, of course, the image predates science. The image of the circular, interconnected structure of social, psychological and spiritual health appears in nearly every culture's mythology. Long ago, Chief Seattle said, whatever man does to the web he does to himself.

Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux holy man who witnessed the destruction of his people during the mid-1880s, described his vision of the web, which he called the nation's hoop, this way:

I was standing on the highest mountain of them all, and round about beneath me was the whole hoop of the world. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.

Later, he described the loss of his nation's hoophow all the marching animals grew restless and afraid that they were not what they had been, and began sending forth voices of trouble, calling to their chiefs, how he looked down and saw that the leaves were falling from the holy tree all the animals and fowls that were the people ran here and there, for each one seemed to have his own little vision that he followed and his own rules; and all over the universe I could hear the winds at war like wild beasts fighting. The nation's hoop was broken like a ring of smoke that spreads and scatters and the holy tree seemed dying and all its birds were gone.

And another image of the web, much older: The prophet Isaiah, circa 730 B.C., wrote, There is One Who is dwelling above the circle of the earth, the dwellers of which are as grasshoppers, the One Who is stretching out the heavens just as a fine gauze, Who spreads them out like a tent in which to dwell.

In our society, it is easy to lose sight of the web. To mend our hoop, our protective gauze, we must envision the whole ecology and not only the parts. Yet, even in the dark, we can find the faithful remnants and begin to weave. And as our hands hold the strands, the strands begin to hold us.

In a previous book, Childhood's Future, I described the new web that must be woven to support children; this book furthers that theme, but shifts the emphasis to other passages of our lives.

For many years, as a columnist for The San Diego Union-Tribune, I have been drawn to people who are acutely aware of the web, even if they call it by other names. In Kansas, a woman in her nineties, who is God's friend but asks nothing of Him; a Chippewa chaplin who liberates prisoners through a burning doorway in time and space; a woman in Oregon who has found her one true place; a Navajo flutist who helps people listen to their inner voicesand my wife and children and friends and many others who teach me daily about the connections of time and spirit.

This book is a collection of thoughts, theirs and mine, about the web in our lives, and our lives in the web.

The Strand of Family

Although it is made of thin, delicate strands, the web is not easily broken. However, a web gets torn every day by the insects that kick around in it, and a spider must rebuild it when it gets full of holes.

E.B. White

The Little Things

THE LITTLE THINGS. The click of your wife's makeup bottles and brushes in the bathroom in the morning, the subsurface sound of them, a kind of music. The accompaniments: the older boy's bedroom door opening and shutting in haste, a faucet running, a gust of wind in the eucalyptus, the last rain on the window. The little things are what we remember, what we know, of family life. Of life.

The large events have their place, but even the large events of a family's passage are assembled from little things. The rush to the emergency room and the way the air feels there and the brave little chin thrust up beneath the mask, the small choked cry and the soundespecially this soundof the thread being pulled through the wound, and the way the little hand holds tight to your finger. The little things.

Without realizing it, we can neglect the little things.

Though I have never divorced and my vow is for life, I have like most people experienced a broken relationship or two. Grief does not attach itself so much to the empty space left by the other person, a loss often too abstract to grasp, but to the little things. The vertical space in the closet where familiar clothes once hung. The smell on the pillow or, on the street, a stranger's accent that conjures up a silenced voice.

When our parents and loved ones die, little things come back. Returning home after a death, you find a quilt that wrapped around you long ago, and you remember how the hands felt as they tucked you in. You find yourself startled by the way the dishes are arranged in your parent's kitchen cabinet; you are surprised because you know the arrangement, and you did not know it was so familiar until you looked at it within the context of loss.

The impression most remembered from my grandmother's death is not of the large fact of her body in the casket, but of coming into her cold kitchen a few days afterward and seeing the jar of mincemeat cookies, which she often made for me and my brother. In the jar, then, they were covered with mold.

Next page