1996 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

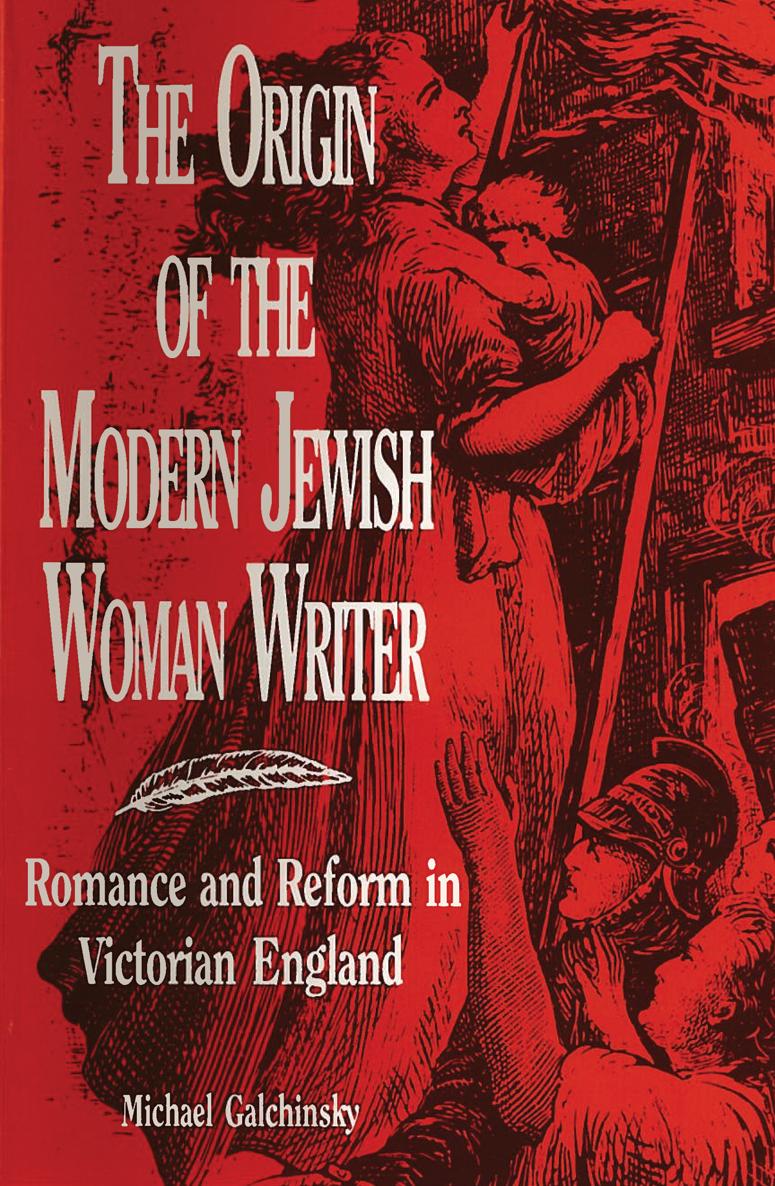

Galchinsky, Michael.

The origin of the modern Jewish woman writer : romance and reform in Victorian England / Michael Galchinsky.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4444-6 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4445-3 (ebook)

1. English literatureJewish authorsHistory and criticism. 2. Jewish womenGreat BritainIntellectual life19th century. 3. Women and literatureGreat BritainHistory19th century. 4. English literatureWomen authorsHistory and criticism. 5. English literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. 6. Aguilar, Grace, 18161847Criticism and interpretation. 7. JudaismGreat BritainHistory19th century. 8. JewsGreat BritainHistory19th century. 9. Jewish women in literature. 10. Judaism in literature. 11. Jews in literature. I. Title.

PR120.J48G35 1996

823.8099287089924dc20 95-41199

Wayne State University Press thanks Michael Dunn and The Jewish Museum, London for their generous permission to reprint material in this book.

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

To Sarah Galchinsky, who learned all she could of Judaism in her shtetl, Trisque, by listening outside the window of her brothers school, while waiting to take him home.

To Rose Gvirtz, who taught three daughters how to be Jews, the only Jews in the pioneer town of Fort Collins, Colorado.

My wish in the following very simple story, was to pourtray a Jewess, with thoughts and feelings peculiar to her faith and sex, the which are not in general granted to that race, in Tales of the present day.

Grace Aguilar,

Adah, a Simple Story

P REFACE

During my research in London, my attempts to recover materials relating to womens experience of Jewish modernity were frequently fruitless. As it turned out, I was sometimes luckiest when I was not trying. One afternoon I walked into the Jewish Museum of London with no other intention than to see the famous paintings of Moses and Judith Montefiore. Since the curator seemed amenable to talk, I happened to mention that I was interested in the writings of the Victorian Jew, Grace Aguilar, not expecting him to have heard of her. But on the contrary his eyes lit up, and he told me that the museum had been in possession of all of Aguilars tributes, diaries, and unpublished poetry and fiction manuscripts since the early part of this century. The papers had been donated by a historian, Rachel Lask Abrahams, who had gathered the material from the personal papers of Aguilars mother Sara. Nothing I had read had even suggested that this material existed. Unfortunately, the curator continued, from the time the documents had come to be housed in the museum, they had been inaccessible to scholars, because the institution did not have facilities for scholarly research. Just three months before I arrived, however, the museum had arranged to transfer the documents to the Manuscript Library of University College London, where if I was so inclined I might go directly that afternoon. The curator said he would be happy to write me a note of recommendation, if I cared for one.

A month later, I put in a request for the sole surviving copy of Marion Hartogs Jewish Sabbath Journal, the first Jewish womens periodical anywhere in the world in modern history. The Jewish Studies librarian at University College London returned an hour later to tell me that after an extensive search, he had concluded that the copy had been irretrievably lost. This was a blow, for I suspected that the Journal would illuminate many of the most difficult questions raised by the study of the Anglo-Jewish womens literary community. For example, how had the community come into being? and what purposes had it served for the women involved? I put an advertisement in the following weeks Jewish Chronicle, looking for Hartogs ancestors. No one responded. Two weeks later I had almost given up when, as I was sitting in the library, the telephone rang. It was the librarian. He had been in a basement in another part of the library searching for something else when, of all things, he had come upon the Journal, sitting in a stack of unrelated seventeenth-century documents. Did I still want to see it? I rushed over to the Manuscript Library to find a frail, brittle, and water-damaged sheaf coming apart in tiny bits in my hand. By the end of the day, the bits had covered my shirt. So this was what was meant by recovering history.

Like the archaeologist, the archival researcher knows that history is comprised of the material objects extant from the past. In the case of Jewish womens literary history, archival resources are more limited and exhaustible than in other areas, because women were exempted from participating in the intellectual life of Jewish communities for most of Jewish history. Yet many more documents relating to womens experience of Jewish modernity remain extant than scholars have generally recognized. Because earlier historiographical models neglected or underestimated the differential effect of Jewish modernity on men and women, the substantial wealth of nineteenth-century fiction and periodical literature dealing directly with that subject has remained largely unexplored. This lack of attention to basic sources in turn has meant that larger synthetic studies purporting to tell the story of Jews modernization repeated the absence of gender as an analytical category. Over the last ten years or soin studies of French, German, American, and English Jewsthere has been a recognized need among feminists and other scholars interested in gender to return to the archives and recover what has been neglected.

This book focuses on a critical but forgotten moment in the development of Jewish womens writing, the moment in which modern Jewish women transgressed their traditional exemption from literary endeavor and began to publish books. Between 1830 and 1880, Jewish women in England became the first Jewish women anywhere to publish novels, histories, periodicals, theological tracts, and conduct manuals. In their own time, Grace Aguilar, Marion Hartog, Judith and Charlotte Montefiore, and Anna Maria Goldsmid were acknowledged by Christians and Jews alike as the most significant theorists of English Jews entrance into the modern world. Their romances, some of which sold as well as novels by Dickens, argued for Jews emancipation in the Victorian world and womens emancipation in the Jewish world. These texts served as emblems of Jews desire to become acculturated to modern English life while simultaneously maintaining a distinct collective identity.