by the same author

Boatowners Mechanical and Electrical Manual (4th edition, McGraw Hill/Adlard Coles)

Marine Diesel Engines (3rd edition, McGraw Hill/Adlard Coles)

Nigel Calders Cruising Handbook (McGraw Hill)

How to Read a Nautical Chart (2nd edition, McGraw Hill)

Cuba: A Cruising Guide (Imray)

For Pippin and Paul, to tell the story of a voyage they were too young to remember, and in memory of our dear friend and intrepid sailor, Peter Hancock.

Contents

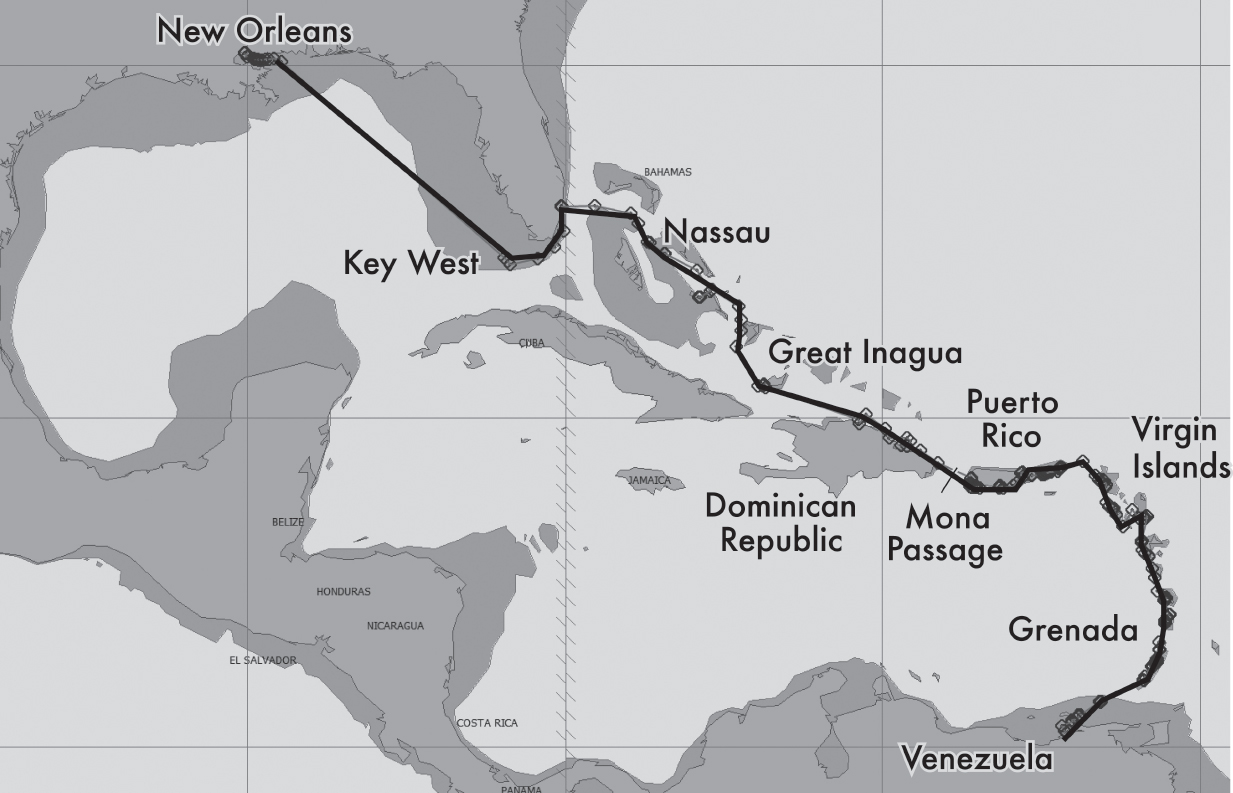

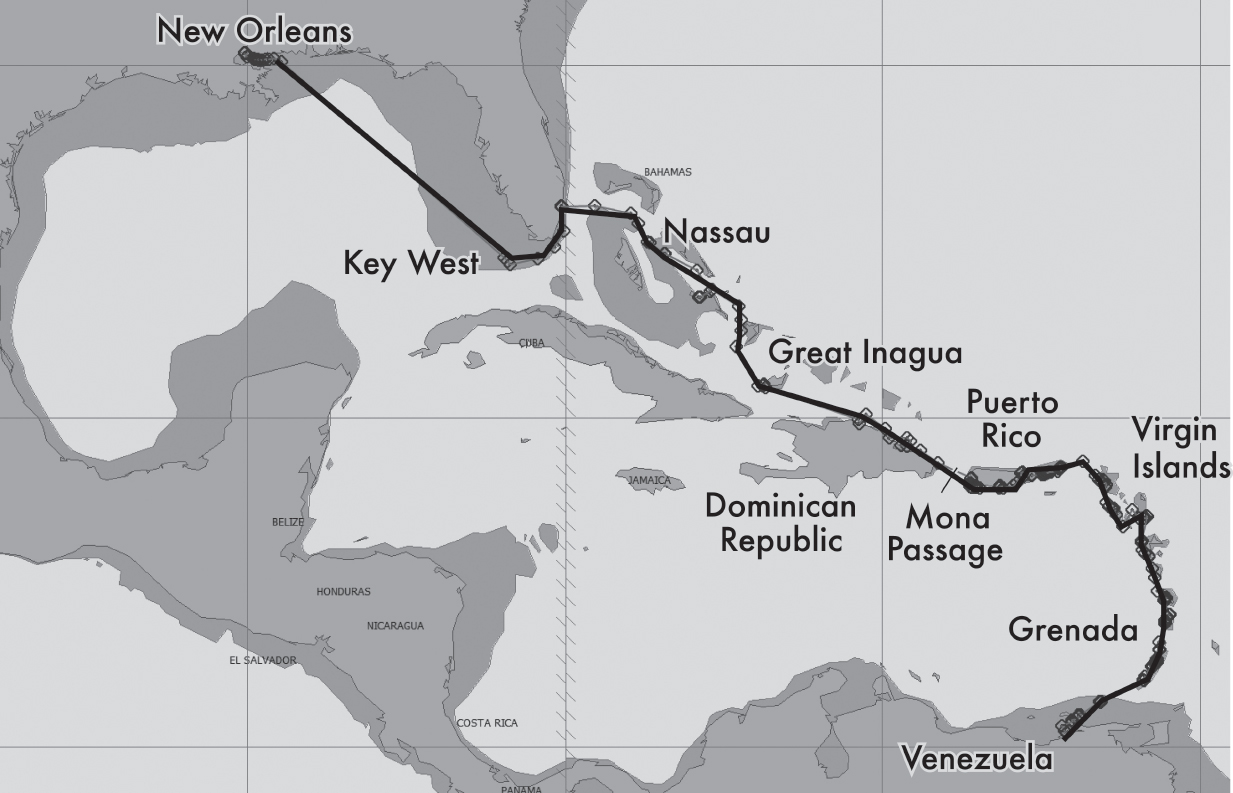

Track of Nada from Mandeville, Louisiana, to Cumana, Venezuela, January to June 1987.

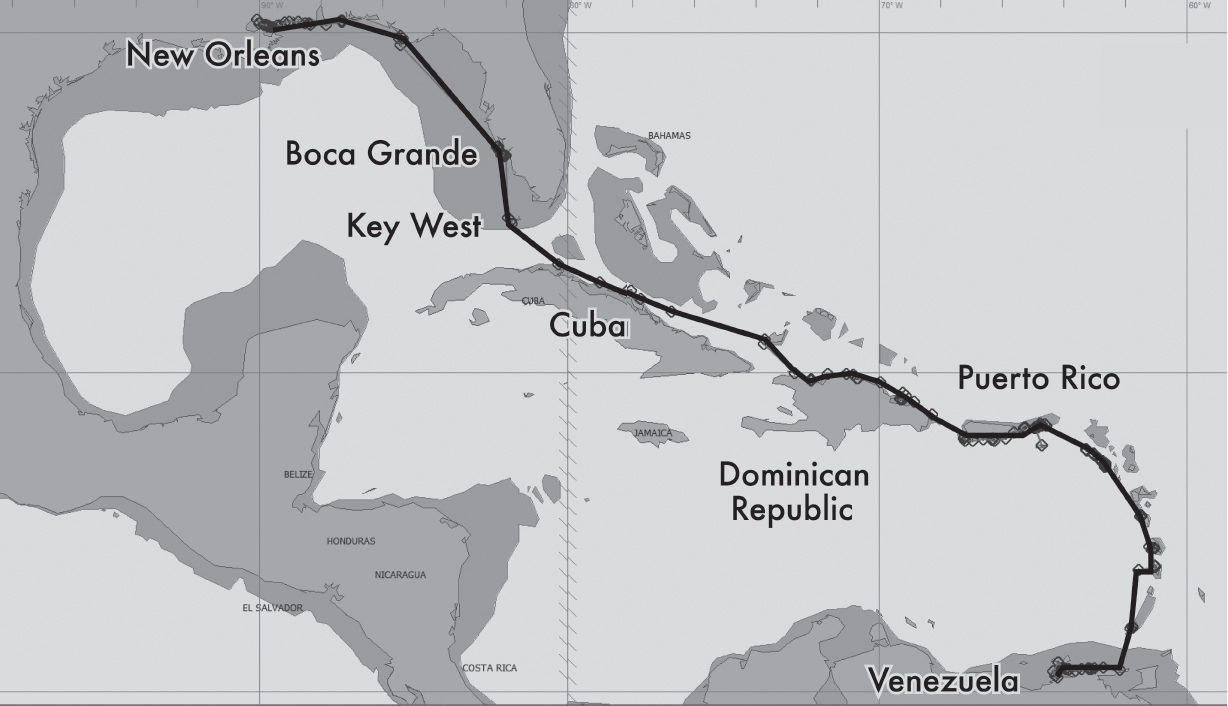

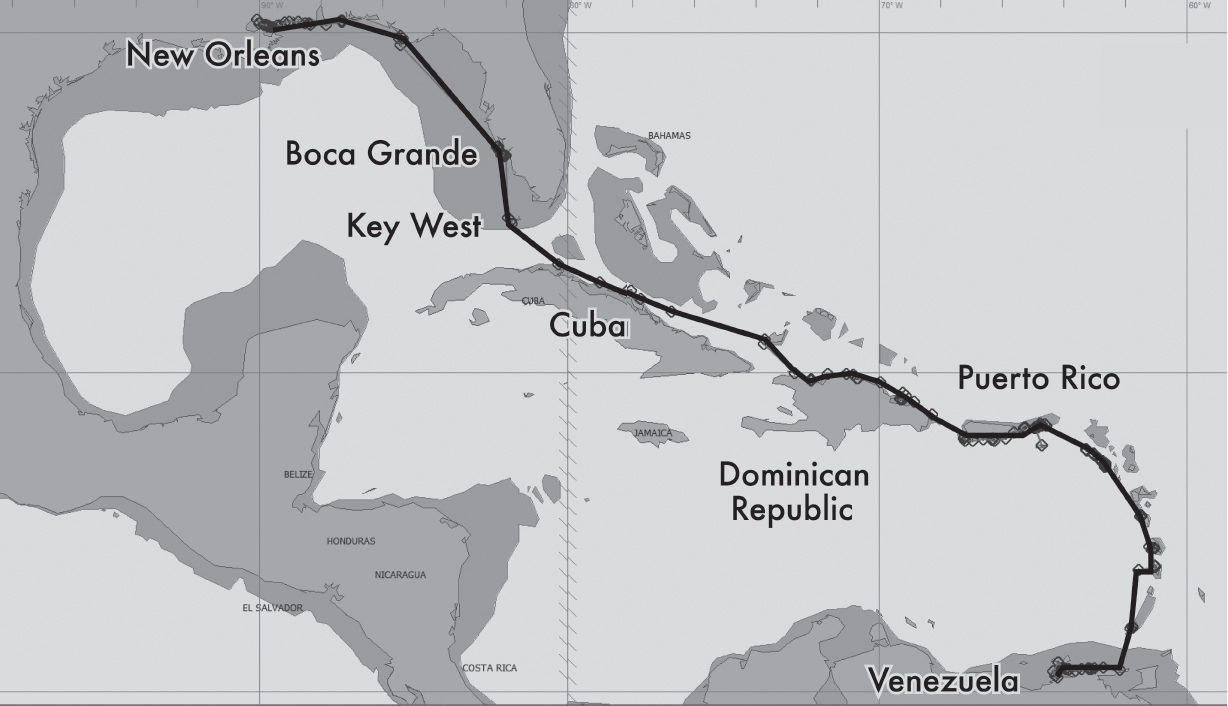

Nada s return track, from Cumana, Venezuela, to Mandeville, Louisiana, December 1987 to June 1988.

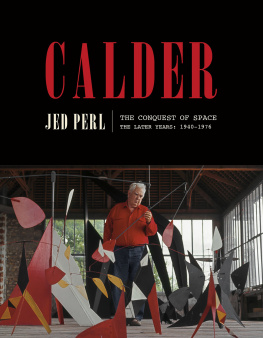

I wrote this book, describing my familys first long cruise, in 19878, thirty years ago. It sat in a filing cabinet until I recently came across it and dusted it off. It catches us at a turning point in our lives when Terrie and I are starting a family and I am just beginning to make my mark as a marine technical writer. We have recently finished building our dream boat and are setting off as inexperienced, impecunious cruisers, driven by a love of adventure and a sense of optimism to explore the world. We have a lot to learn!

It is remarkable how much has changed in the succeeding three decades, but it is also remarkable how little has changed.

Perhaps nothing has changed more than navigational processes. In 1987 we were in the twilight of sextant-based navigation and at the dawn of recreational electronic positioning. We had a sextant and sight tables on board, and knew how to use them (I could not today), but also a first generation satellite navigation (satnav) system. It gave us intermittent fixes, often hours apart, that were generally accurate but sometimes wildly erroneous. There was no such thing as digital cartographyall plotting was done on paper charts, most of which were based on surveys from the 1800s and very few of which carried precise inshore detail. I still have those chartslooking at them today I am amazed that more cruising boats were not lost. Most coastal navigation was carried out with the help of a hand bearing compass (which I still use) and early cruising guides.

Shakedown Cruise is suffused with anxious nights sailing through rock- and reef-strewn waters, unsure of our precise position. On longer passages, such as across the Gulf of Mexico, we would sometimes deliberately aim a mile or two to one or other side of our intended landfall so that if we did not recognize where we were when we sighted land we would at least know which way to turn. This is a far cry from today, when we at all times know our position, often to within six feet, with it constantly plotted and updated in real time on digital charts. Between then and now we have lived through an astonishing technological shift that is not even remotely comparable to any previous advancements in the art of navigation.

In 1987 we were also at a point in time when lifestyles on board cruising boats were transitioning from camping out to an ever-closer approximation to living at home. We had a fridge and freezer (although I went through three systems before we achieved something reasonably efficient and effective), hot and cold running water (but only after running the engine to heat the water), and, in terms of those days, a moderately powerful electrical system built around a high-output alternator and a relatively large battery bank. We even had a microwave (although most of the time we did not have the energy to run it and instead used it as a bread storage bin!). This was luxurious cruising. Today these things are simply taken for granted.

In the pages of this book we frequently have trouble setting our anchor in the thin-sand-over-rock found in many Caribbean anchorages. The CQR was the default anchor within the cruising community. We also had a Danforth anchor as a lunch hook and a bronze fisherman anchor as a backup (we still have it). The modern generation of scoop anchorsthe Spade, Rocna, Manson, Ultra, Mantusare qualitatively better than anything available to us in 1987, removing one more anxiety from the cruising life. When the wind pipes up we sleep easy these nights in a way that we never could in the past.

Throughout Shakedown Cruise I am troubled by problems with my back (I did some damage working in the oilfields many years ago). Other technologies have now taken much of the hard work out of sailing, notably roller furling sails, electric winches, electric windlasses (ours was manual), and bow thrusters. We have them all on our current boat. Nada, the boat we sail in these pages, was ketch-rigged to break up the sail plan into smaller and more manageable areas. The genoa on our current boat has more sail area than all of Nadas basic sails put together. We control the genoa at the push of a button. Whereas a 40-foot boat was considered a large cruising boat for two people to handle in 1987, today boats over 50 feet are commonplace.

Then there is the boat itself. We built Nada toward the end of the 1970s home-built era. There was already a vigorous debate concerning the relative merits for offshore cruising of traditional long-keeled, narrow beam, heavy displacement, double-ended boats versus lighter fin-keeled, wider beam, transom boats. I read every book available and came down on the traditional side. We then overbuilt Nada, especially the deck. The result was a relatively slow and tender boat with poor windward performance. This comes through in every chapter of Shakedown Cruisewe constantly struggle to make headway upwind and sometimes give up. On the other hand, Nada could take anything the weather gods could throw at us and never oncein all the tens of thousands of miles we put under her keelpounded when coming off a wave. Although still conservative, our subsequent boats have looked less and less like Nada. Performance has improved considerably with no loss of safety or comfort. Unlike most modern boats, we still dont pound.

There is a substantial downside to the technological advances. Sailing has become expensive and prone to system failures. We are in danger of losing sight of why we go cruising. And in these pages there are some eternal themes that hold true as strongly today as they did for us in 1987. It is why Terrie and I are still cruising together.

There is the freedom that comes from casting off and heading out to sea. Once away from the dock you are in your own little universe, accountable to no one but yourself. In our increasingly regulated world there are not many mechanisms for achieving this, and none more effective than cruising. There is the sense of adventure and the desire to explore, traits deeply embedded in the DNA of all of us that have driven mankind to sail over the horizon since the dawn of history. There is the excitement of discovering new places, especially those inaccessible by any other means. There are the wonders of nature experienced, from sailing in company with humpback whales in the Dominican Republic, to enjoying a tropical sunset in a pristine Caribbean anchorage, to watching puffins hop in and out of their burrows on a Hebridean island.