Contents

Guide

ALSO BY JEAN-GEORGES VONGERICHTEN

Home Cooking with Jean-Georges:

My Favorite Simple Recipes

(with Genevieve Ko)

Asian Flavors of Jean-Georges

(with Genevieve Ko)

Simple to Spectacular:

How to Take One Basic Recipe to Four Levels of Sophistication

(with Mark Bittman)

Jean-Georges:

Cooking at Home with a Four-Star Chef

(with Mark Bittman)

Simple Cuisine:

The Easy, New Approach to Four-Star Cooking

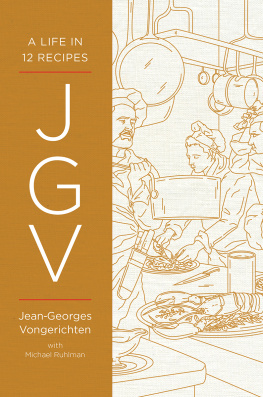

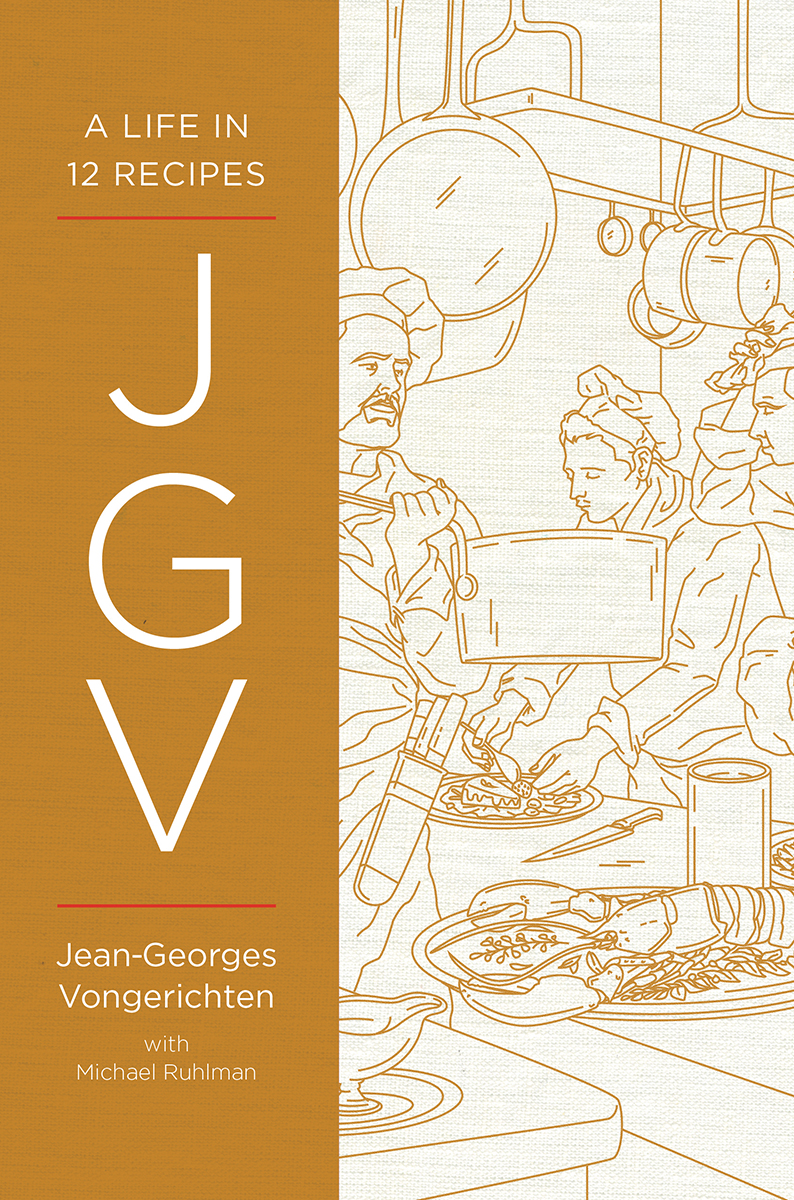

JEAN-GEORGES

VONGERICHTEN

with MICHAEL RUHLMAN

JGV

A LIFE IN 12 RECIPES

Copyright 2019 by Jean-Georges Vongerichten

All rights reserved

First Edition

Drawings made by Jean-Georges Vongerichten are on .

Photos on pages are from Jean-Georges Vongerichten.

Photograph is from Lois Freedman.

Photograph is from Daniel Del Vecchio.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by Catherine Casalino

Jacket illustration by Jared Oriel, adapted from Restaurant

Chef in the Kitchen (painting) by G. Marchetti, 1893/Courtesy of Jean-Georges Vongerichten

Book design by Lovedog Studio Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-0-393-60848-9

ISBN 978-0-393-60849-6 (Ebook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

I would like to thank the city of New York,

my adopted city, and its people for supporting

me for the past thirty-three years and

allowing me to fulfill my dreams.

Good food is the foundation of genuine happiness.

AUGUSTE ESCQFFIER

CONTENTS

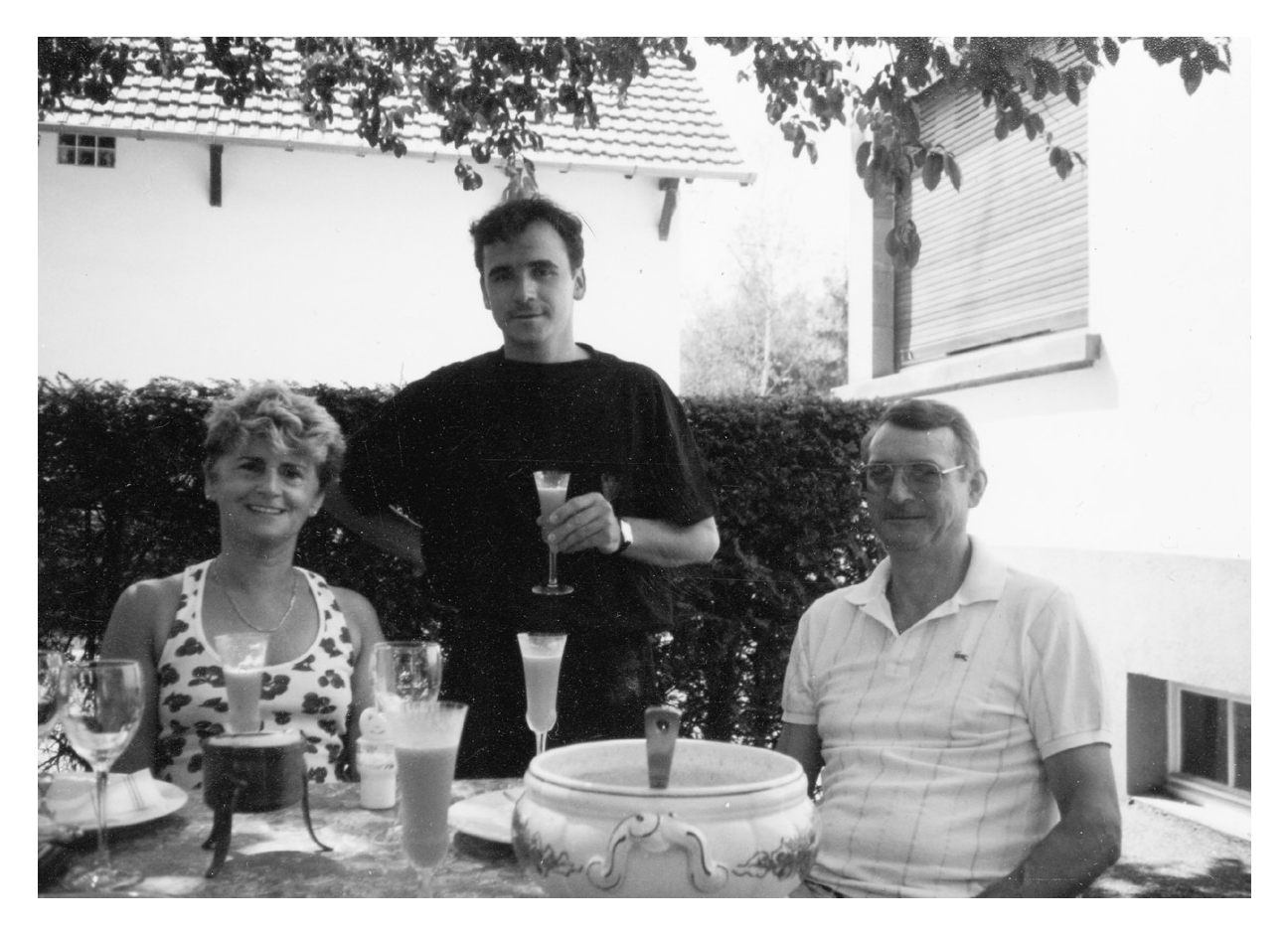

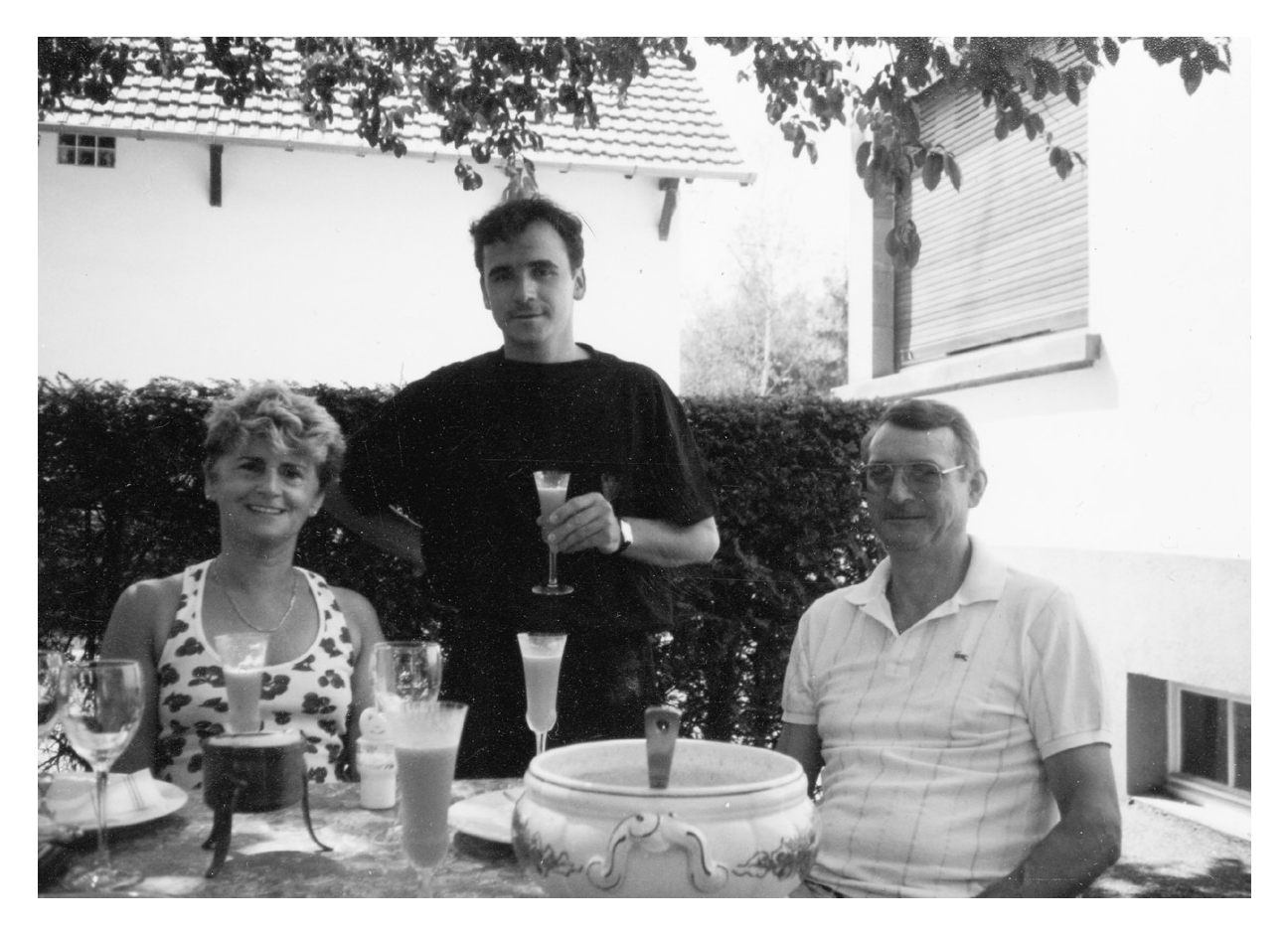

With my mom and dad enjoying a cocktail in summer. We had a lovely patio where we ate our meals. The year is about 1988, on a visit home from New York, where I was chef of Lafayette in the Drake hotel.

1.

LISTEN TO YOUR CHILDHOOD

YOU ARE STARTING OUT AND ASKING YOURSELF HOW TO proceed in this world of cooking, or if to proceed in this world. What path to follow? What does it mean to be a cook and a chef? What, you wonder, do you need to know? Im asked all the time, How did you do it? This question isnt easily answered. But my hope is that my story, how I got to where I am, my evolution as a cook and then a chef, might help you answer those questions for yourself.

I didnt know I wanted to spend my life cooking. I was an aimless country boy from Alsace, a region of flatlands in easternmost France. The Black Forest and the German border were five miles away, and I grew up speaking not French but, rather, Alsatian, a German patois (I wouldnt learn French until age five, when I began school). I liked to have fun. We lived in a house my great-grandparents had built in 1833; it had a river on one side and woods on the other. Me, my two younger brothers and older sister, my parents, my grandparents, two aunts and their kids, all in the same house. The house was big, so I was lucky to have my own room, but still, it was a crowded household. We were on top of one another.

My family owned a coal business. Our coal came down the river on barges. My parents worked hard. My dad sold coal and wood. He drove the delivery trucks. He did everything, from delivering fuel to collecting bills to entertaining clients. He would even go into the forests to get the wood, which would have to dry for a year before it could be sold. But their biggest struggle by far, a never-ending problem, was getting people to pay. They were always chasing after clients. Even my mom would go through the town knocking on doors to get money. I think maybe thats why I do the work I do. People have to pay me before they leave. Honestly, that remains one of the great things about the restaurant business, not having to chase down customers as my mother was continually doing.

The other lesson I learned, I see now, was to not do your business where you live. My parents work never left them. They would get calls in the middle of the night from people saying their heating had gone out. So my father had to go to them to make sure they had heat in the middle of a frigid night. Me, when I leave the restaurant, I leave my work behind. I suppose I could get a call at midnight saying theres a fire in the kitchen. But even then Id be able to say, Call 911! This work is so intense and so constant, the capacity to turn it off is fundamental to your being able to restore yourself for the day to come.

As a boy, I was carefree. I had a wonderful childhood. I played in the woods and climbed the mountains of coal behind our house. My whole childhood I was black with soot.

Throughout my childhood and youth, perhaps tellingly, the kitchen was the busiest part of our house. My mother, who was twenty-two when I was born, in 1957, cooked. As I noted, ours was a packed household, just with the immediate family alone. But not only were we three generations under one roof, we also had a number of employees working for our business there. They would need to be fed. And clients would always be invited to meals, as well. This meant that every day, we had a three-course lunch for around forty people. My mother had lunch on the table at twelve-thirty sharp. Dinner appeared at seven-thirty. Sharp. Every day. Looking back, this stays with me. Her rigorous schedule. Lunch, twelve-thirty, every day, every week, all year long. It never varied, and she was never late. Dinner: seven-thirty. Period.

Lunch in France was the big meal, but for us, even dinner was bigtypically twenty people for dinner. Imagine it if you can. Every day, lunch for forty, dinner for twenty. It was a mini restaurant. When I look back on it now, I understand that I basically grew up in a restaurant doing sixty covers every dayabout the same number of seats I have at my restaurant Jean-Georgesand I watched the whole process each day of my childhood. I absorbed the preparation, the attention to timing, the organization needed to get that much food, prepare it, and serve it for that many people.

My mother didnt work alone, of course; everyone helped. But she was the chefthe head of the kitchen. When I was a child, I didnt cook, though I watched the whole production. Everybody waking up early in the morning, peeling potatoes. That was my benchmarkeveryone worked. Eventually, at around age ten or eleven, when I could reach the counter, I worked as well. I learned my mothers palate, which was impeccable. Nothing ever needed salt. She made things bright with aggressive aciditywhich, youll notice, remains one of the keystones of my cooking and seasoning. And by the time I was age twelve or so, she would have me taste for seasoning because I was so good at it. Soon I developed a palate more nuanced than hers.