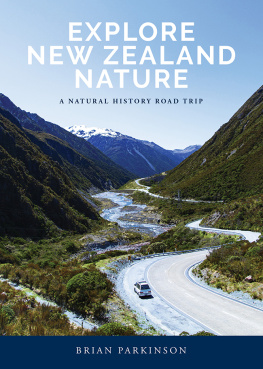

EXPLORE NEW ZEALAND NATURE

To Keith Lees

He tohu iti o te whakamihi

Published in 2022 by White Cloud, an imprint of Upstart Press Ltd, Auckland

www.upstartpress.co.nz

26 Greenpark Road, Penrose, Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright 2022 Upstart Press Ltd

Copyright 2022 in text: Brian Parkinson

Copyright 2022 in images: Shutterstock

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

ISBN 9781990003639

eISBN 9781990003905

Project Editor: Duncan Perkinson

Designer: Andrew Davies

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

F or millions of years New Zealand sat alone in the vastness of the South Pacific, a unique world where changes, when they did occur, did so at a glacial pace. Then humans arrived on the scene with all the grace and charm of a cyclone.

First came Maori, who in a few short centuries deforested great parts of both islands and with the aid of the kiore and kuri harassed, harried and hunted a greater part of the kararehe whenua, the original fauna, into extinction.

The arrival of Pakeha exponentially worsened the situation. Starting with Cook, early explorers, sealers, whalers and settlers accidentally introduced vermin whose effects on the native fauna were catastrophic. Cook and other early visitors, such as de Surville, also deliberately introduced foreign animals, always with good intentions but seldom with comparable results.

Since then, all too often the attitude towards our environment has been an unhappy compromise between those who thought the resources were inexhaustible, or who just didnt care, and those who thought the opposite and were determined to get theirs while they could. Perhaps most shameful were the bird collectors people like Walter Buller and Andreas Reischek who collected thousands of birds and drove some species to the point of extinction.

From their writings it is apparent that these gentlemen were convinced that many birds were doomed to extinction, but it also seems that they devoted entirely too much of their energies to bringing this state about. It is often argued that the collectors were children of the time and that their actions were typical of the Victorian era. This argument is, however, facile: both Thomas Potts and Richard Henry were contemporaries of Buller and Reischek and both had a much more compassionate understanding and feeling for the land and its creatures.

In my wanderings over the past 75 or so years throughout New Zealand I have noted the dramatic and often draconian changes that are still altering our landscape, an acceleration of the cultural component of our natural history. After all, natural history is as much about history as it is about nature.

This history takes many forms and comes to us in many ways: from the sayings, legends and place names of the tangata whenua, by way of the often florid but always readable accounts of the early naturalists and explorers, and so on to the commentaries of todays observers more dispassionate but no less caring than their predecessors.

And finally, there is the eloquent testimony of the remnant populations of todays forests and offshore islands stark legacy of the last 1,000 years of human history. Travelling to such places as the Huiarau Range, Kakapo Bay, Piopiotahi and Papamoa brings a pang of nostalgia for those hapless creatures immortalised in name, but now vanished forever.

And yet a sense of perspective is needed. The changes are constant and continuing and were not started, but rather accelerated, by the arrival of humans on our shores.

So it is interesting to contemplate what New Zealand was like when both James Cook first stepped ashore and when Kupe first beached his canoe.

CHAPTER 1

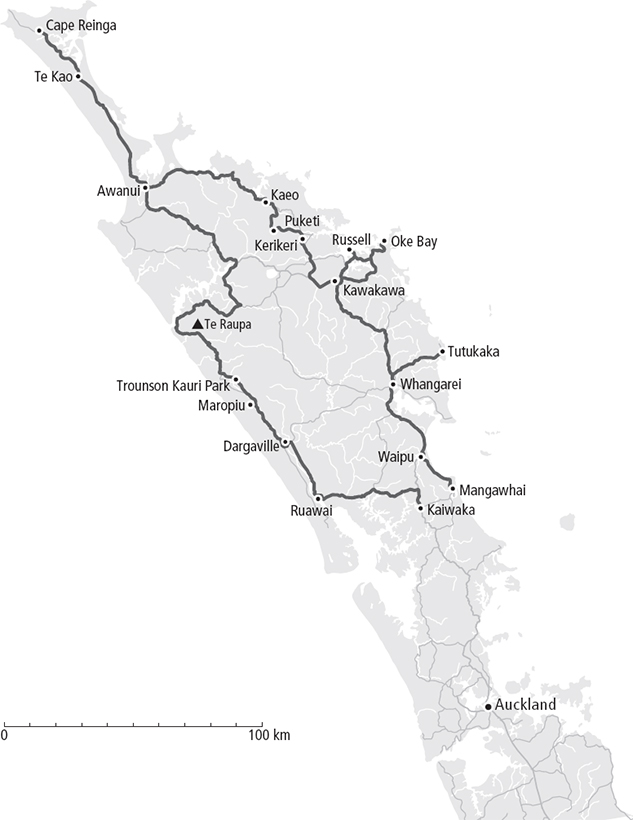

Northland/Te Tai Tokerau

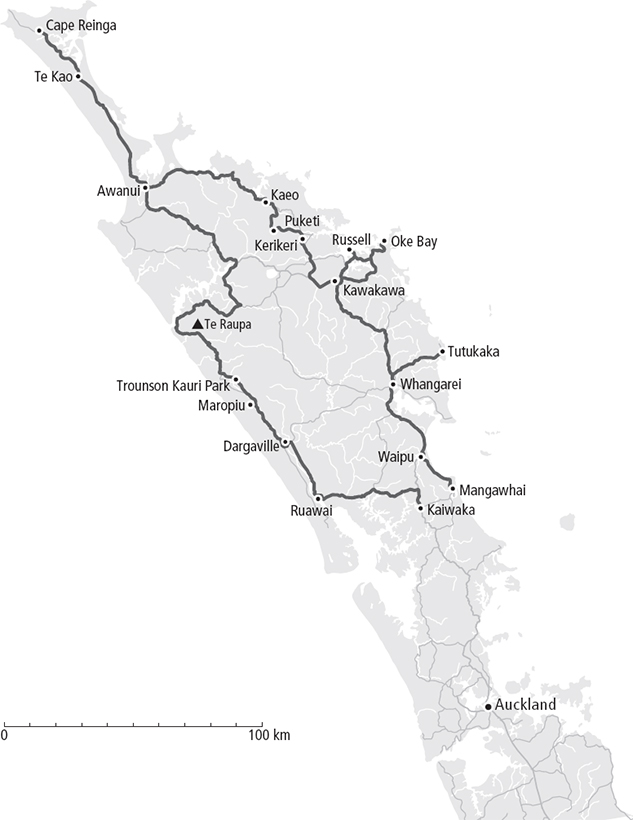

T he long narrow peninsula extending nearly 400km north of Auckland is known as Northland or Te Tai Tokerau or occasionally, in flights of fancy, as the winterless north.

The east and west coast of the peninsula differ dramatically. In the east there are dozens of superb sandy beaches and excellent harbours which once provided stages for the coastal shipping which served the north. By contrast, the west coast extends in a long curve from Cape Reinga to Auckland, broken only by the Kaipara and Hokianga harbours. This is sometimes called the Kauri Coast.

Geologically, Northland has a varied history. Ancient volcanic plugs, such as those of St Peter and St Paul at Whangaroa and Mt Manaia at Whangarei, contrast with vast sedimentary deposits and the extensive dunelands backing onto the western beaches. Although nowhere do the mountains reach any great heights, the land is rugged and there are few plains except those edging rivers. This factor, along with often poor soil, delayed development of the north until relatively recently.

When Pakeha arrived Northland was covered with forest, dominated by kauri, a tree of great size and with excellent timber. The logging and milling of kauri was the principal industry north of Auckland for many years after Pakeha settlement and, although there are a few stands left, the great trees that once flourished in this area are now mostly gone. Today, the small patches of native bush that remain between Auckland and Whangarei are usually too small to support many native birds and the larger stands have few tall trees.

From Kaiwaka, 23 km north of Wellsford, an alternative route north heads out to the coast at Mangawhai. This scenic route rejoins SH1 at Waipu. A few kilometres south of Waipu and just before the road swings inland away from the coast, take Johnson Point Road to the Waipu Estuary. NZ dotterels and variable oystercatchers breed here along with a range of other shorebirds, including the rare fairy tern.

If you stay on SHI, on your right just north of Kaiwaka is Pukekaroro, its symmetrical 300 m cone clothed with young kauri forest, and just north of Pukekaroro is the bare, fluted dome of Bald Rock. SH1 climbs steeply up the southern side of the Brynderwyn Hills, from the top of which there is an expansive view towards the craggy volcanic peaks of the Whangarei Heads, the sweep of Bream Bay and the Hen and Chicken Islands. It was on the largest island Hen/Taranga, that the North Island saddleback (tieke) survived after being exterminated by introduced predators across the rest of the North Island a classic example of a predator-free island being the salvation of a species. Starting in 1964, tieke were successfully transferred by the Wildlife Service from Taranga, first to Middle Chicken, then to Red Mercury, Cuvier and Big Chicken. Tieke flourished on Cuvier and it then became a major source of birds for subsequent translocations. These included Kawhitihu, Hauturu, Tiritiri Matangi and Kapiti. Some of these islands in turn became sources for ongoing transfers to various other islands and pest-free mainland sites including Zealandia Eco-sanctuary in Wellington, and Tawharanui. Two species have been translocated to Taranga from other islands the little spotted kiwi (kiwi pukupuku) from Kapiti and the stitchbird (hihi) from Little Barrier. The kiwi have thrived but the hihi translocation seems to have failed.