Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

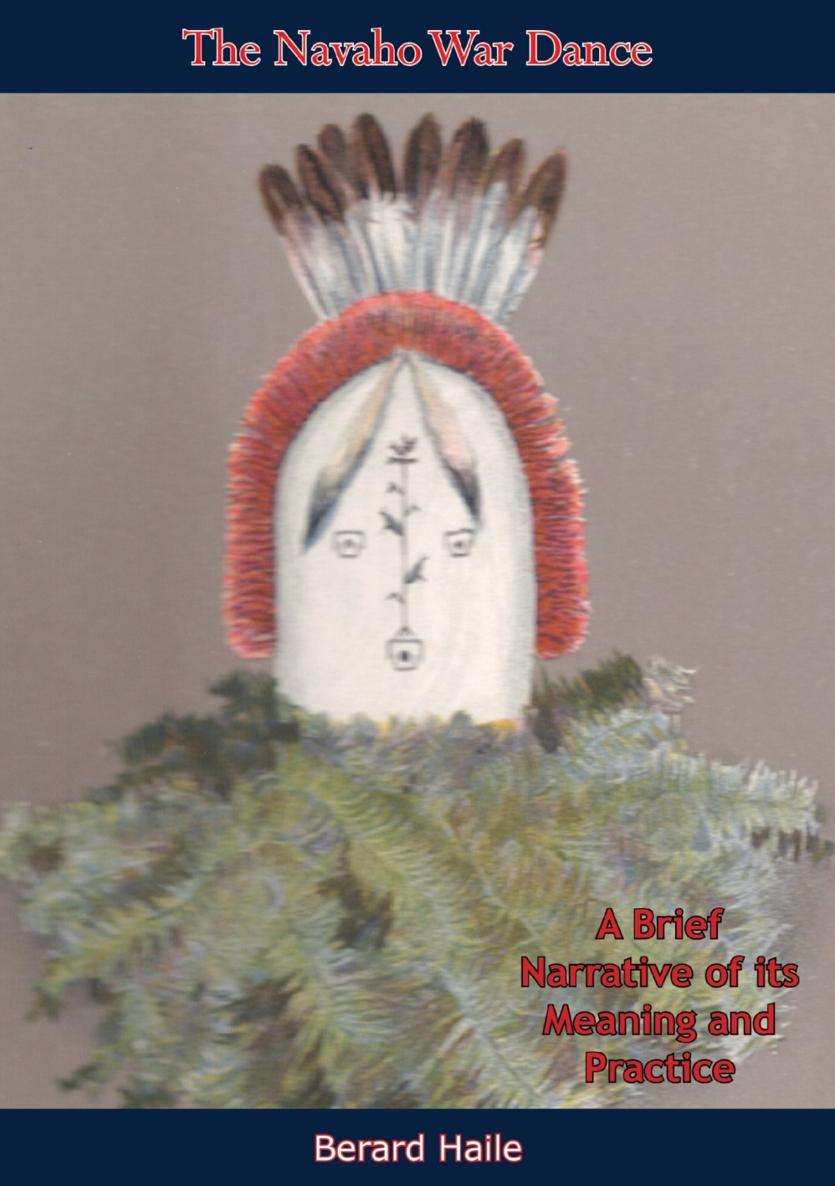

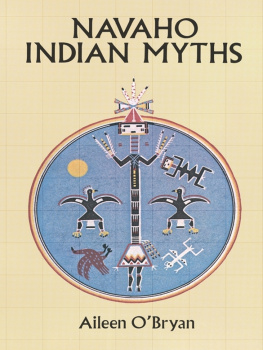

THE NAVAHO WAR DANCE

SQUAW DANCE

BY

BERARD HAILE

A FOREWORD.

The average American wants to know what its all about. Are Navahos always at war because War Dances are practically a regular occurrence, say in the summer and fall months? Who is the enemy? His scalp? The author strives to give accurate information on these and other points of the Navaho War Dance.

Variations which occur on some details have been ignored as of little interest to the general reader. Our aim however has been a description of the ordinary three-night dance counting, as the Navahos do, the nights which follow the acceptance of the rattle stick. Whatever precedes this acceptance, like the time spent in building the hogan, obtaining a scalp, preparing and dispatching the rattle stick, is not included in the three nights of the dance proper.

Throughout the Navaho area the dance is known to white residents as the squaw dance. Possibly they have followed the American trend of mind to look upon any Indian woman or female as a squaw, because Massachusetts Indians called them so. The Navahos do not use the word squaw, but plainly speak of the girls dance and that always means unmarried girls. Read the narrative yourself!

WHY A WAR DANCE IS HELD.

Residents on the Navaho reservation can tell you that since their return from Ft. Sumner in 1868 the Navahos have not been at war with the U.S.A., nor with the neighboring Pueblos, Mexicans, and their traditional enemies the Utes. Yet no summer passes without a War Dance, even several of them, somewhere on the reservation. This does not mean a preparation for a future war. In matter of fact the thousands of young Navaho men who went overseas in the recent world war had no war dance held for them in preparation for combat. More than likely however the survivors who fought in Italy, Europe, and the Pacific will be confronted with the necessity of a future War Dance.

This does not mean that these boys are going to celebrate victory with the native War Dance. But it does mean that they are full fledged warriors who have seen and met and conquered the enemy; have seen and possibly lost blood in the struggle. They have seen many slain enemies. They will not forget these sights any too soon. In years to come they may recall these scenes, perhaps be haunted by them in sleep and dreams. Eventually too many such recollections and reminiscences may impair their health and strength, cause loss of weight and appetite, and bring on a generally run-down condition alarming alike to their families and relatives. These will discuss matters and try to find the reason for ill health and lack of vitality. A diagnosis, if you like, but not on the order of an American physicians diagnosis.

Organic diseases and indispositions are not too well known to the Navahos at large. Thats true even if the returned soldiers may help to bring some of this much needed knowledge back home. But the bulk of the tribe will follow their old reasoning: This boy of ours was sent to war, he came in contact with people who are not Navahos, therefore they are foreigners and enemies to us. They are pursuing him. That is evident from his sickness and general ill health. The ghosts of these enemies are at the bottom of this, so something must be done to break their hold.

The reasoning is traditional with the tribe. If we except the returned soldiers of World Wars I and II, very few, even of the older Navahos now living, have seen actual warfare. But a number are returned Carlisle, Haskell, Phoenix, or Albuquerque students. Some have intermarried with the whites, Mexicans, Pueblos and other Indian tribes, or have sought work in railroad and other towns. Add to this that wagons, autos, and railroads have greatly facilitated travel and made contacts of Navahos with outsiders a matter of daily occurrence. Think too of contacts made possible by an annual affair such as the Gallup Ceremonial at which representatives of various Indian tribes perform.

Such contacts with outsiders are not frowned upon by the tribe. While many tribesmen do not encourage extra-tribal marriages, neither these nor sexual relations of Navaho men and women with outsiders can be prevented altogether. Nor is it impossible at times to witness train land car wrecks which spell injury to outsiders and their death. Funerals and cemeteries are disliked as they seem to imply too great familiarity with the dead. But if a Navaho has touched the corpse of a foreigner, has even, inadvertently stepped on a foreigners remains or grave, there is a strong possibility of a reaction on the part of this foreigner.

Let us remember, when we speak of the War Dance, that the Navahos alone are the People and din means the Navaho as a tribe or people, and a Navaho as opposed to a Zuni, Mexican, American, Japanese, Chinese, or Russian. All of these are ana enemies, and Navahos dont care about the country which gives these enemies their specific names. They dont know much about geography outside of their own little reservation. This fits the pattern of the War Dance fairly well, since the dance is not a preparation for war on enemies whose names the singer does not know. But it is a post-war ceremony and even here he does not give a tinkers dam about the enemys country. But his song will express the rejoicings of old men and women folk of Crownpoint, Lukachukai, Chinlee, Black Mountains, Tuba City or Leupp, that one of their boys and sons has slain enemies outside of the confines of the Navaho country. Hence we dance, we play the flute, we rejoice! Call him a Ute if you will, thats a traditional enemy! Call him a coyote, buzzard, an enemys wife weeping besides the corpse of her late husband, or anything else contemptibleyou describe the slain enemy! What matter if the listeners dont know where the enemys country is, it fits the warriors case in any event!