2009 by Michelle Wibbelsman

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wibbelsman, Michelle

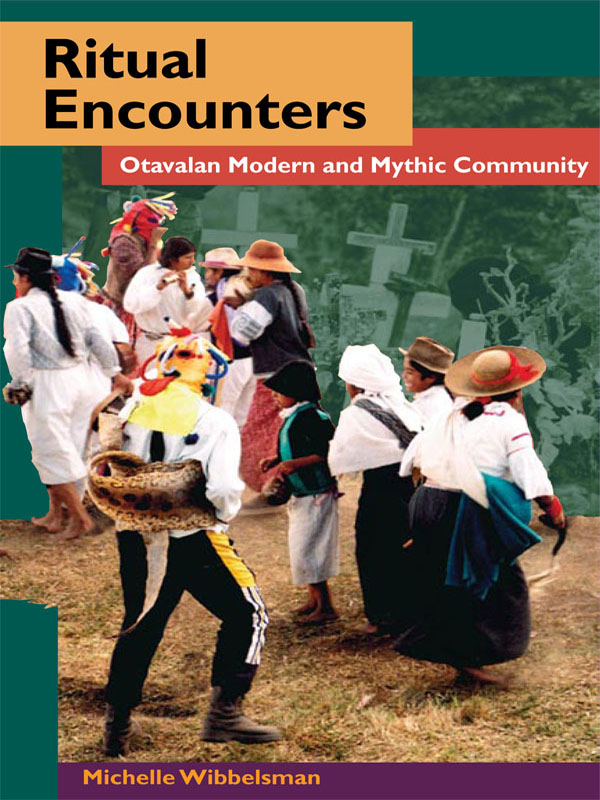

Ritual Encounters: Otavalan Modern and Mythic Community / Michelle Wibbelsman.

p. cm. (Interpretations of culture in the new millennium)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03397-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07603-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Otavalo IndiansSocial life and customs.

2. Otavalo IndiansRites and ceremonies.

3. Otavalo mythology.

4. Imbabura (Ecuador)Social life and customs. I. Title.

F3722.1.08W53 2009

305.898'323dc22 2008027199

Preface

Ritual in the highlands of northern Ecuador is ubiquitous. It marks the cadence of life in indigenous communities. Among Otavalan indigenous people of Imbabura province, ritual is defined by the deep knowledge that emerges from an oscillating rhythm of everyday life and celebration, and from a sustained conversation with beings in other realms of existence. It is in these ritual contexts of physical and metaphysical encounter that Otavaleos invoke their mythic and historical past as integral to the formation of their ethnic and moral identity as a modern community.

Mayman Ringui? Choosing a Field Site

I arrived in Imbabura by a winding path that first took me away from my native country and then returned me to it. I was born in Quito, Ecuador, in 1968 to an Ecuadorian mother and a North American (U.S.) father. In 1981, a period of political and economic transition in Ecuador, we relocated to Texas. I was brought up in the urban Ecuadorian private educational system, and yet knew little about my own country. It was not until I entered college in the United States that I became truly aware of the multiethnic and multilingual diversity in Ecuador. This sparked my desire to return to the Andes for research purposes. While completing my master of arts degree in Latin American studies at The University of Texas at Austin, Dr. Gerard Bhague encouraged me to visit Otavalo and put me in contact with Ecuadorian ethnomusicologist Carlos Coba at the Instituto Otavaleo de Antropologa. In the summer of 1995 I traveled to an Ecuador I had never known before.

Ethnographic fieldwork requires the researcher as a curious observer to be open to random encounters and the opportunities they extend. Ethnography is a method insofar as we gain glimpses of culture in details we are often not looking for, but are fortunate to witness and trained to notice. At the heart of these anthropological pursuits lies an ability to discover similarity across differences. This is how in 1995 I came to meet Blanquita and her familyby chance and mutual curiosity. Nos simpatizamos, as one would say in Spanish, and this affinity more than any preconceived research agenda defined the circumstances of my fieldwork.

I met her in a craft workshop, where she wove handbags along with other Otavalan women. During our brief exchange, she extended an invitation to a family baptism in the community of Ilumn Bajo. It was something I could have just as easily dismissed as polite conversation as followed through with. This was the first time I would venture outside the city of Otavalo at night. I stumbled along the old railroad tracks following the irrigation channel, per Blanquitas directions, equipped only with her fathers nickname, Cuchara, as a sort of password that validated my presence in the community and ensured help along the way.

When I arrived, I was put immediately to work in the kitchen as another pair of hands. My task of frying enormous quantities of chicken integrated me into the informal interaction and agitated pace of production behind the scenes, and allowed me to cut through the awkwardness of being received as a special guest. After the excitement of serving dinner to the new godparents was over, I ate in the kitchen with the rest of the women. As it got late, I was invited to spend the night at Blanquitas house. I piled into a bed with her two youngest siblings, and slept soundly on a reed mat under heavy wool blankets. Little did I know that five years later, this would be my home.

The process of moving away from Ecuador and returning periodically to rediscover it in a different light has guided the evolving insights I share in this book. My initial research trip led to subsequent summer visits in 1997 and 1999 and to my extended doctoral investigation in 2000 and 2001.

I lived in Ilumn with Blanquitas family for fourteen months in 20002001. My research aimed to investigate indigenous ritual practices and to analyze the ways by which their interconnected and progressive character offers a unique perspective on Otavalan identity, morality, and modernity. As a single woman, I initially operated in the private sphere of the home. I gained invaluable insight into the daily lives of my indigenous family as I became involved in cooking for work parties, taking animals to pasture, attending school meetings and helping children with their homework, washing clothes in the spring, and planting and harvesting crops. I attended mass, sat in on community meetings, and partook in private rituals including family house cleansings, baptisms, funerals, and prayer sessions. I also sold chickens and guinea pigs at the live animal market and hunted for june bugs in the highland moor when they were in season. This is what anthropologists call deep immersion in a culture through the method of participant observation. It is these dayto-day experiences that provided the context for cultural interpretation and theoretical framing of my research on ritual and identity.

As my research developed a comparative dimension, I extended the geographical scope of my project. Another friend by mutual liking and chance encounter, Luis Pacfico Fichamba, Paci, involved me with a second-tier indigenous organization in the town of Cotacachi. There I met Segundo Anrrango, Rumiahui Anrango, and Edy Zaldumbide, among many other dedicated compaeros. I volunteered at UNORCAC (Union of Indigenous Organizations of Cotacachi) as a member of a team charged with documenting area cultural traditions as part of a sustainable development project funded through the Inter-American Foundation. UNORCAC oversees forty-two communities in Cantn Cotacachi. Working for this organization extended my opportunity to do collaborative work with community members. In addition, it provided introductions and transportation to distant communities, many of them accessible only by motorcycle. I was also invited to participate in collecting oral narratives on regional traditions for a project at Jambi Mascaric, a holistic medicine center affiliated with UNORCAC. Director Magdalena Fueres and I met and talked often. She provided important insights regarding my observations, as did local researchers Carlos Guitarra and Rosita Ramos, whom I accompanied, on occasion, on field interviews throughout the canton.

Interpretations of Culture in the New Millennium

Interpretations of Culture in the New Millennium

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.