Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tober, Diane, author.

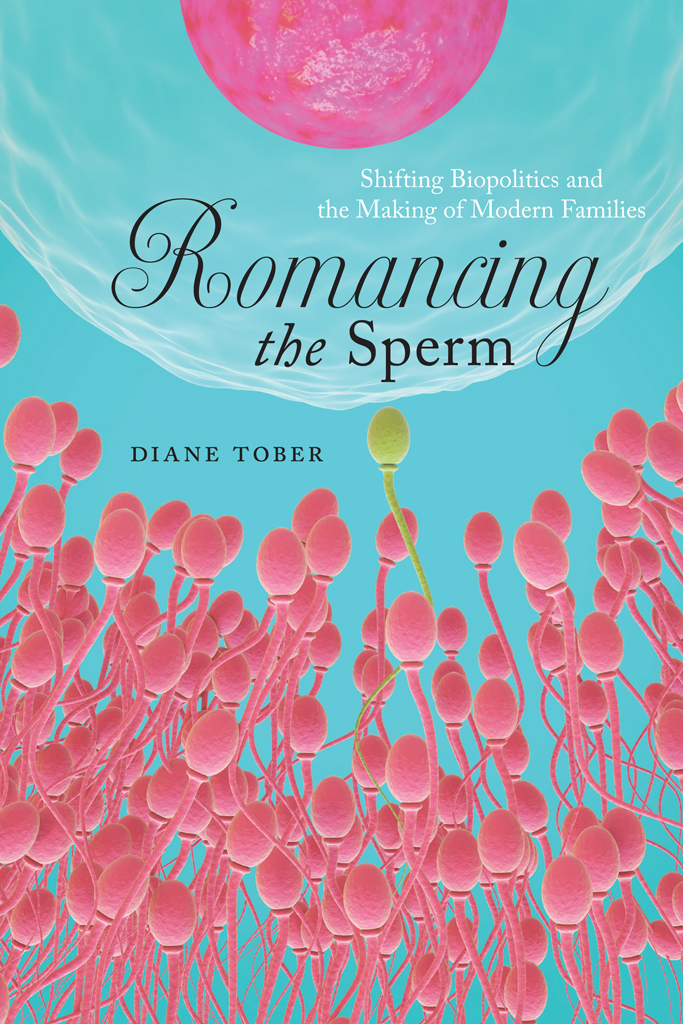

Title: Romancing the sperm : shifting biopolitics and the making of modern families / Diane Tober.

Description: New Brunswick : Rutgers University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004643| ISBN 9780813590790 (cloth) | ISBN 9780813590783 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Artificial inseminationSocial aspects. | Human reproductive technologySocial aspects. | Single mothers. | Families.

Classification: LCC HQ761 .T63 2018 | DDC 618.1/78dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004643

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2019 by Diane Tober

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

Manufactured in the United States of America

This book explores how single women and lesbian couples created their families, on their own terms, in the 1990s. Some women purchased sperm from sperm banks; some approached men they knew to be sperm donors. Some women were just starting the process of trying to conceive, some were successful and were either pregnant or raising children, and others were unsuccessful, following years of failed infertility treatments. This project is an attempt to lend a sensitive ear and a compelling voice to what women go through when attempting to conceive a child on their own or with a female partnerespecially in light of the social, medical, legal, and political environments that marginalized families created outside heterosexual nuclear family structures, which are commonly viewed as the norm.

Language around sex, sexuality, and gender has changed dramatically since I first started this work. At the time, terms like cisgender woman or trans woman or masculine identified did not exist. All participants in my study were either in a couple or single, considered themselves women, and were lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual. Some who were lesbian or bisexual identified would also identify as dyke, butch, femme, and so on. I try to be as specific as possible in respect to how people identify themselves throughout my work. Since I did not have trans people in my initial research sample, I am using the terms that were appropriate at that time. I do not intend to marginalize transgender identities or reproductive experiences, but these were not part of my study; however, they are worthy of further research. As an anthropologist, it is important to stay as close as possible to peoples own categories and self-identifications. Where appropriate, I do include discussions of trans identities and experiences.

Participants in this research repeatedly asked me two questions: Are you lesbian? I am not. Do you have kids? The answer to the second question is more complicated, and it changed throughout the course of my research. I assume the people I spoke to over the course of this research wanted to know my position regarding both them and the research I was conducting. While this research started off as an interesting anthropological project that would fulfill the requirements for my doctoral degree in the University of California, Berkeley/University of California, San Francisco, medical anthropology program, over the course of many years, it turned deeply personal.

I came to this project through my work as a research assistant on a National Institutes of Healthfunded project exploring gender differences in response to infertility, led by medical anthropologist Gay Becker and reproductive endocrinologist Robert Nachtigall. For this project I ventured into peoples homes, and into their private lives, in order to uncover the struggles heterosexual couples face when dealing with infertility. Many of the stories I heard were tragic: there were numerous accounts of miscarriages, stillbirths, ectopic pregnancies, botched surgeries, and couples life savings spent on infertility treatment. It seemed the lengths people would go to in order to have a biological child were extreme. Yet the few who were successful in conceiving and delivering a healthy baby considered the emotional, physical, and financial sacrifices to be worth it.

Throughout my research, I attended many infertility support groups through Resolve, a national organization that provides support and resources for people with infertility. As a single woman myself at the time, I soon realized that most of the symposiums and groups targeted heterosexual married couples. In 1991, at a Resolve conference at Mills College, I overheard a lesbian couple complain that there was no relevant information regarding the issues they were facing in their quest to conceive a child. I then realized that a study of women attempting to conceive without male partners needed to be done.

At the same time, single women and lesbian couples were calling to volunteer to be research subjects for the University of California, San Francisco, study, but they were turned away because they did not fit the parameters of the study, which was exploring the impact infertility has on married couples and how women and men respond differently. I told Gay of my interest in learning more about womens experiences in having a child without a male partner and asked her if she could refer unmarried women who wanted to participate in the research project to me. As early as 1992, I began interviewing women who called to volunteer for the larger study.

From a research perspective, I was interested in two main questions. First, how do sexual orientation, relationship status, and fertility or infertility affect womens identity? This in some ways mirrors the gender differences question in the larger National Institutes of Healthfunded study, but without comparative difference from men. The second question was, How do women choose a sperm donor when they are not trying to match a male partner? I figured that women may have different criteria when not trying to match a male partner, and how women chose donors could provide deeper insight into how cultural perceptions of genetic inheritance affect individual reproductive practice. Here, I was thinking in terms of the linkages between culture and biology, and how individual and cultural interpretations of attractiveness, intelligence, creativity, race, health, and other characteristics come to the fore when choosing a donor. I perceived donor choice as a reflection of the kind of children women wanted to bring into their lives.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.