2003, 2016 by University Press of Colorado

First edition 2003. Second edition 2016.

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 987-1-60732-527-7 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-615-1 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williams, Jean Calterone, 1966 author.

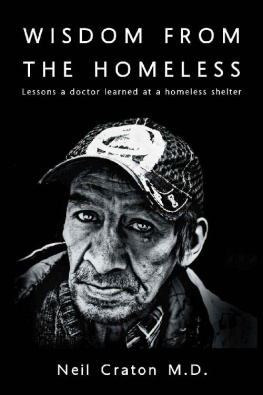

Title: A roof over my head : homeless women and the shelter industry / Jean Calterone Williams.

Other titles: Homeless women and the shelter industry

Description: Second edition. | Boulder, Colorado : University Press of Colorado, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029076| ISBN 9781607325277 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781607326151 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Homeless womenServices forUnited States. | Single mothersServices forUnited States. | Womens sheltersUnited States. | HomelessnessUnited States. | Victims of family violenceUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV4505 .W53 2016 | DDC 362.83/985dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029076

Cover image: Stephanie Carter/Getty Images.

For Cass and Shane

Introduction

Though at one time in our history passing a man huddled under a blanket on the sidewalk or observing a woman asking for money outside a grocery store was a rare occurrence, we now witness such sights daily in large cities in the United States. A relatively invisible political issue affecting a small portion of the population until the early 1980s, homelessness became increasingly problematic throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in the United States. Although the economy rose and dipped during these decades, as did the percentage of people living in poverty, homelessness appeared to be a relatively intractable problem. The numbers of people newly homeless generally did not abate, even during periods of economic growth. According to the US Conference of Mayors report, the demand for emergency shelter increased every year from 1985 to 2014, through periods of both economic stagnation and growth. Homelessness also came to be seen as a pressing social problem because of the statistics citing women and children among the fastest-growing segments of the homeless population. Women were seen as a surprising subset of the new homeless; few women were among the hobos and itinerant workers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And in part because homeless women often have children with them, womens homelessness introduced new concerns and understandings about what it means to be on the street. Today most estimates indicate that families with children make up at least 30 percent of the homeless population. With approximately 1.6 million children becoming homeless annually, the number of homeless children in the United States is at a historic high.

Research suggests that the reasons for homelessness are complicated and multilayered. First and foremost, homelessness is a product of poverty:

[A] variety of complex social system dislocationsan increasing rate of poverty, a deteriorating social safety net, the steady loss of low-skill employment and low-income housing, and othershave created a situation... where some people are essentially destined to become homeless. In so many words, we now have more poor and otherwise marginalized people than we have affordable housing in which to accommodate them.

While the official US poverty rate has hovered around 15 percent since 2010, estimates suggest that a third of all people were near poor and poor. In addition to poverty being widespread, the depth of poverty represents a pressing problem in the United States. Approximately 6.6 percent of households have an income under 50 percent of the poverty line, or roughly $12,000 annually for a family of four, which presents a tremendous barrier to housing stability for a considerable portion of the population. As Edin and Shaefer discovered in their research on impoverished families, in 2011 approximately 1.5 million households lived on cash incomes of at most $2 per day, per person, a calculation that includes cash welfare payments but does not include in-kind assistance like food programs. When poverty is that profound, people clearly struggle to afford basic necessities such as housing, food, clothing, and utilities and are at considerable risk of becoming homeless.

Low-income housing is in short supply and housing subsidies are not widely available to those whose incomes qualify them for assistance. With almost 12 million extremely low-income renters (those who earn less than 30 percent of area median income), there are just over 4 million available units that are affordable for this group. More than 70 percent of households earning less than $15,000 annually pay more than 50 percent of their incomes for rent each month, putting them at severe risk for homelessness. Thus, housing supply has not kept pace with the numbers of low-income people whose incomes require low-cost housing if they are to remain stably housed. In addition, among those who qualify for government-funded low-income housing vouchers, only a fourth get access to a voucher, and low-income households can expect long waiting lists for federal rental assistance.

Struggles with poverty and low-income housing shortages interact with several other convoluted causes of homelessness, often a combination of what are termed structural and individual issues, such as low wages and the declining value of the minimum wage, family violence, lack of access to welfare supports, mental illness, and drug and alcohol use. Both men and women suffer from a lack of low-income housing, low wages, and sporadic employment, but women also contend with domestic violence and the traditional responsibility of caring for children. It is difficult to capture the interaction of these multiple reasons for homelessness without sustained and intimate knowledge of homeless womens lives. Statistics tell only part of the story; poverty rates, unemployment rates, and welfare rates cannot fully describe womens homelessness. For these reasons this project relies on the rich and detailed information revealed through homeless womens personal narratives, describing the causes of homelessness in homeless womens own voices.

In addition to the causes of homelessness, I also question the meanings of homelessness through homeless and housed peoples perspectives. That is to say, homelessness refers to the lack of a dwelling considered standard in our society, the literal lack of a roof over ones head. But homelessness also symbolizes, in a very visceral way, all the things we as a society attribute to poor peopleit represents the lack of personal responsibility, the loss of a work ethic, and a general disassociation from the norms and trappings of middle-class society. In analyzing portrayals of homelessness, which both homeless and housed people help to create, this study also looks at how such meanings of homelessness affect the kind of help homeless people are offered.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses.