Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2014 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Special discounts for bulk quantities of titles in the Stanford Economics and Finance imprint are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department of Stanford University Press. Tel: (650) 736-1782, Fax: (650) 736-1784

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chiswick, Carmel U., author.

Judaism in transition: how economic choices shape religious tradition / Carmel U. Chiswick.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-7604-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8047-7605-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. JudaismEconomic aspectsUnited States. 2. JewsUnited StatesEconomic conditions. I. Title.

BM205.C495 2014

296.0973dc23

2013047799

ISBN 978-0-8047-9141-0 (electronic)

Typeset by Thompson Type in 11/13.5 Adobe Garamond

Judaism in Transition

How Economic Choices Shape Religious Tradition

Carmel U. Chiswick

STANFORD ECONOMICS AND FINANCE

An Imprint of Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

To my parents, who taught me how to be Jewish; to my husband, who helped me be a Jewish economist; and to my children, from whom I learned what it is all about.

Tables and Figures

Tables

Figures

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK OWES ITS CREATION to the inspiration and encouragement from many teachers, colleagues, and students over the years. From Professors Gary S. Becker and Jonathan R. T. Hughes I learned that any interesting subject is worth studying from an economic perspective. From Professors Laurence R. Iannaccone, Barry R. Chiswick, and Evelyn L. Lehrer I learned that religion is an interesting subject for which economics provides important insights. Professors Rela Mintz Geffen, Sergio DellaPergola, Chaim Waxman, and the late Tikva Lecker (zl) encouraged me to apply my economic tools to the study of American Judaism. Rabbi Allan Kensky and Emily Solow encouraged me to share my work with the Jewish community. The project also benefited enormously from the encouragement and editorial advice of Margo Beth Fleming and comments from reviewers who read the manuscript, in whole or in part. Finally, and most importantly, this book could not have happened without the wholehearted support of Barry Chiswick, my husband, mentor, and assistant par excellence.

PART I

Jews as Religious Consumers

Introduction

I GREW UP IN A TIME AND PLACE WHERE Americans looked askance at anyone who was different. Never mind that everyone around us might be considered different by others; our family belonged to a very small Jewish minority in a sea of middle-American Christians. We did not attend the nearby Methodist church; we did not decorate our house with colored lights at Christmastime; and we stayed home from work and school during our religious holidays in the fall. Our neighbors were polite, and I never saw anything like outright anti-Semitism, but there was a clear social distance between us. My parents countered this by developing friendships with other Jewish families, enrolling me in a Jewish after-school program, celebrating Jewish holidays at home, and instilling in me a strong pride in our Jewish heritage. They believed, and I believe with them, that Americas diversity makes it great, and that even people who practice a small minority religion like ours can be equal participants in every other aspect of American life.

Judaism is one of the worlds great religions, enduring and evolving for thousands of years. It spun off two other great religions, Christianity after the first 1,200 years (approximately) of Judaism and Islam more than half a millennium later. Yet the people practicing this ancient religion have always been a minuscule fraction of the worlds population. Todays Jewish population numbers only about 13 million in a world of over 7 billion people, fewer than two Jews for every thousand people in the world. The only country in which Jews are numerically important today is Israel, where about 40 percent of the worlds Jews constitute about 80 percent of the population. About the same number live in the United States, a bit less than 2 percent of the U.S. population. The remaining 20 percent of world Jewry is scattered among many countries in small communities, each a tiny fraction of the total population in their respective countries.

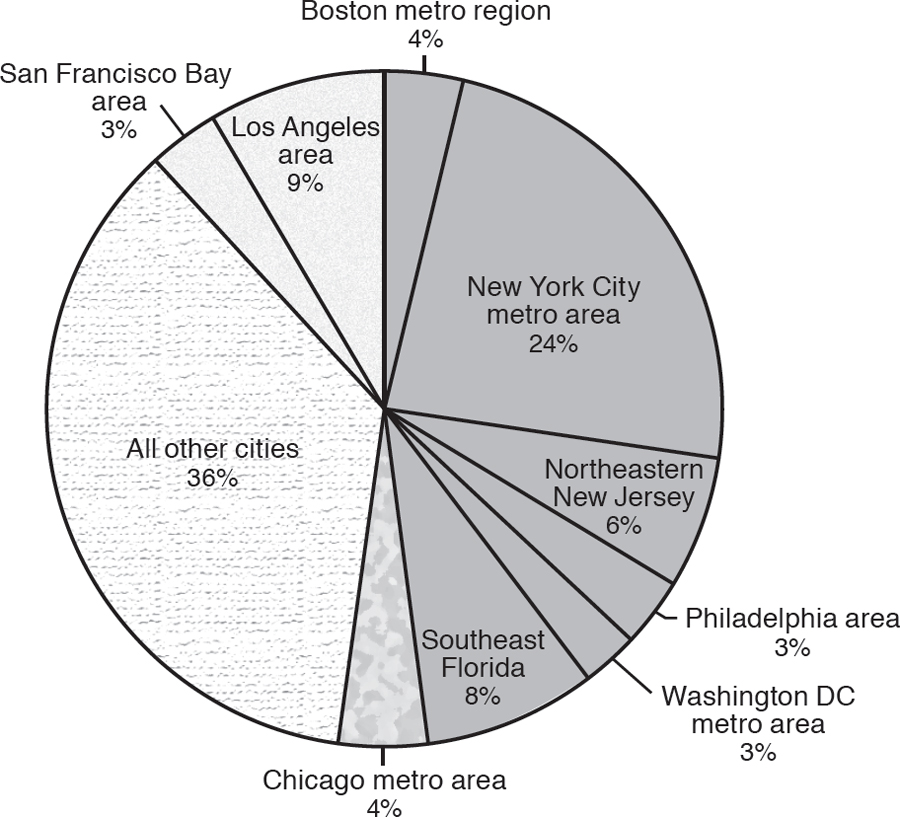

FIGURE 1.1.Jewish population by metropolitan area, 2000.

SOURCE: Computed from Schwartz and Scheckner (2001), Table 3: pp. 262277.

In part because they are such a small minority, Jews typically prefer to live in places where they can join other Jews to form a community. The chart in indicates that nearly two-thirds of the American Jewish population live in and around nine large cities, mostly in the Northeast corridor from Boston to Washington (40 percent), in Florida and California (20 percent), and in Chicago (4 percent). Within the urban Northeast, three-fourths of all Jews live in the New York metropolitan area or nearby New Jersey. Yet because Jews are such a small proportion of the U.S. population, not even the largest Jewish community makes up more than a small fraction of the local population.

Jews share with other small religious minorities a concern with preserving their way of life amid the seductions of a very attractive larger society. No wonder, then, that American Jews have pioneered new forms of Jewish observance, clearly influenced by the democracy and religious pluralism that lie at the foundation of the American experience. Despite their minority status in the United States, however, American Jews are one of the two largest Jewish communities in the world, rivaled only by Israel itself. This means that Americans play a dominant role within world Jewry, especially in the Diaspora (that is, outside of Israel). The religious observance of Jews in the United States is thus an important factor in the evolution of modern Judaism, and American Judaism is a crucial determinant of the shape in which Jewish civilization will be passed on to future generations.

Economics, Religion, and American Judaism

Economics is one of the social sciences, all of which are disciplines that use the scientific methodinvolving observation, theorizing, and empirical testing of hypothesesto study some aspect of human behavior. The aspect of human behavior that is the subject of economic inquiry is how we act when we cant afford to have everything that we want. The technical term for this is scarcity. Some people are so wealthy that they seem to be able to buy anything, but most of us are not, and we have to learn to live within our income. We can raise that income by working longer or harder, by investing wisely, or by receiving a lucky windfall, but for the most part we are limited in these opportunities. Our income is an important determinant of our lifestyle, and our lifestyle choices affect our spending patterns, behavior that is at the heart of the study of economics.