Circle Up

The oak logs glow orange in the fire, casting shadows against the faces circling it. The clan members sit on rough-hewn benches and skins. They are silent after their meal. A sheep carcass hangs from a pole leaned against the rock wall just outside the circle. No predator will dare come close since the people sleep side by side under the limestone overhang that shields them from all but the fiercest storms. The trees beyond the edge of the sheltering rock are silhouetted against the night sky. Between the leaves of hazel, beech, and oak one can glimpse emerging stars. An owl calls and something scuttles in the dry leaves beyond the circle of firelight.

Someone quietly starts to hum a tone that throbs and pulses as the volume rises and falls and ebbs away only to rise again. Another takes up a stick beside the fire and taps out an even rhythm enhancing the singers note. Several more add their voices to become a choir, layering upon one another, a harmony developing, a melody, no words but it feels like a conversation. Still more take up sticks or rocks and bring a new cadence to the song. The percussionist rises and punctuates with staccato intermittent raps against the wall behind them, and the figures shadow starts to leap and dance as someone else adds wood to the fire that bursts into a golden blaze. A few remain silent, eyes fixed on the flames, a head leans against anothers knee, but as the spontaneous music gains momentum, all are seized by the energy; they rise and move in a circle, dipping, spinning, wood clacking, stone tapping, voices clambering and descending with reckless nonconformity. They become transfixed in a kind of trance and time seems to take on a new dimension. The song eventually finds its natural end without any signals; there is no conductor, just a group of beings tied together by forest, fire, and camaraderie. They melt back down into the circle and still no one speaks.

I look at my clan; we have only known each other for a week and it seems incongruous that we could feel so connected in such a short time. They came to me to participate in a class, to learn Stone Age skills and get away from the modern world in which we all live to varying degrees. There is a boy from the village; his grandfather owns the land and this kid is having his first experience away from his family. There is a doctor, a writer, a girl just out of high school, some young travelers not fixed to place who are roaming and experiencing whatever calls them, a plumber, a couple of computer programmers, and a military man. We are in France but we speak five or six languages between us; some struggle to express themselves in English but our common language is as old as humanity itself.

* * *

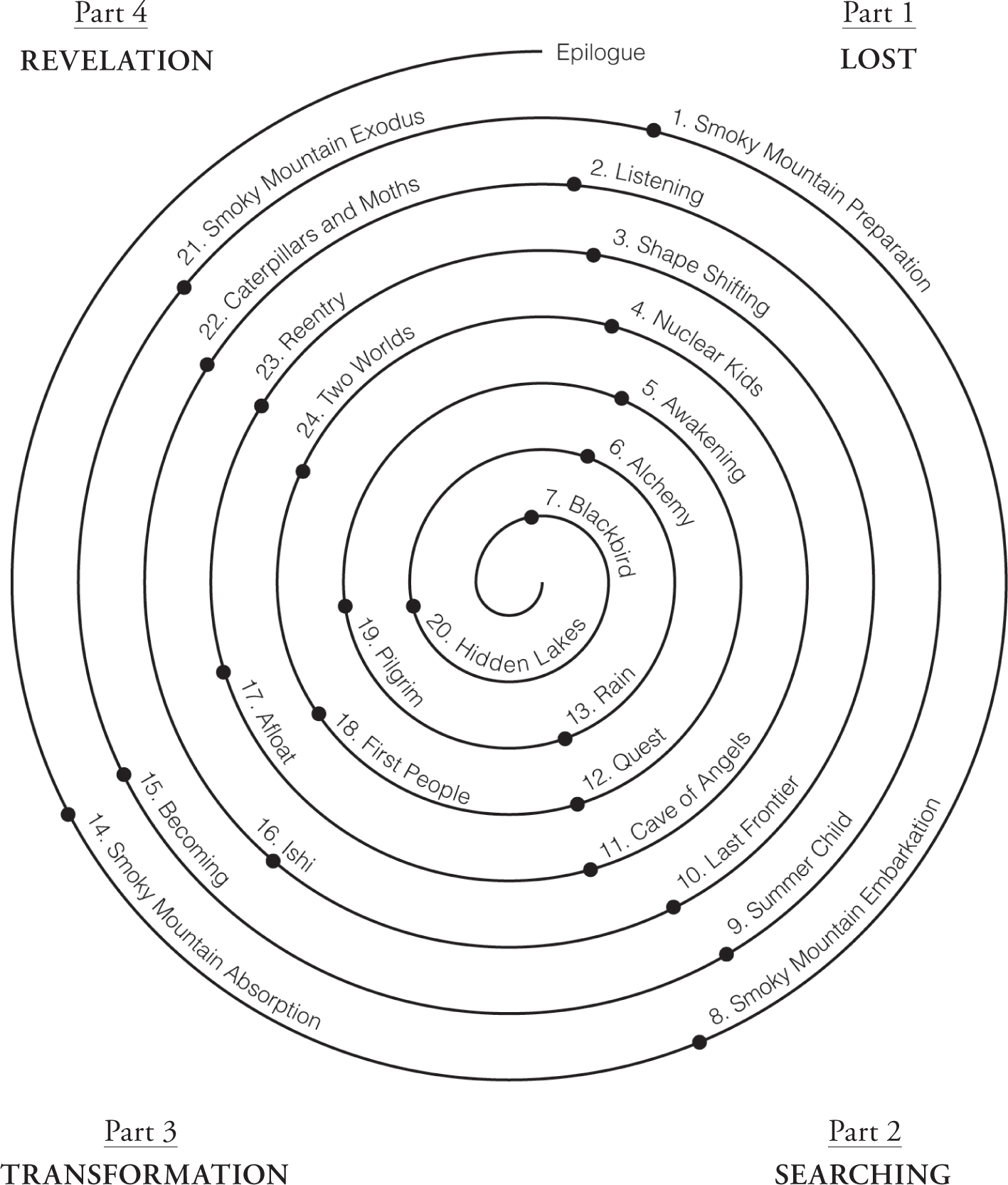

There is a story and a journey I would like to share. Its not a straight path, its more of a circle or a spiral so vast that at times its arc may appear to have a beginning and an end but do not be fooled by this illusion.

This journey is my return, a return to the ways of our ancestors, a return to a simpler life, perhaps to what came before our world was so heavily dictated by our modern conveniences, a return to listening deeply to Earth, and what she has to say. For me, this journey is pivotal because we humans face an immediate peril, the degradation of the environment, which is foundational to our existence, and without which we have no mother to return to.

The story is about us... and Earth.

The earth gives us the opportunity to physically existwithout her we cannot live. We are of Earth, we shape her, she shapes us. We, all too often, seem to have forgotten this.

I want us to remember where we come from. It has never been more important.

Even though I was born in London, one of the largest cities in the world, I have spent most of my adult life living outside, striving for a connection to nature that few of us modern humans achieve. While I am subject to the whims of modernity and will sometimes pass some days or nights in the confines of four walls, hurtle through the sky in an airplane, or trundle across continents in trains, cars, and buses, I have built a life based on entirely different principles. Sometimes described as a primitivist, the last modern hunter-gatherer, or a woman outside of time, I have spent the last twenty years teaching groups of students how to live with the land in a respectful and conscientious manner, and I have also spent this time reducing my own impact and material needs. Even though I have yet to spend more than a month or two each year directly sustained by nature, this curiosity has driven me and given me a life purpose that is all part of my own return.

Return is an invitation to this remembering, an exploration of what a closer relationship with the natural world can offer us and a timely reminderand even a warningof what we stand to lose through our forgetting. Id like to invite you on my journey, from my childhood in London and rural Sweden, to my teenage years in Amsterdam, from my Stone Age experiences with my students in the mountainous western United States, to my personal pilgrimages in the Himalaya, the Middle East, and Namibia.

More than thirty years ago, I crawled out of a sweat lodge escaping the moist oppressive heat and sank fully onto the damp ground. Id grown up in London, spent my teens in punk bands and on its city streets, far from this untouched natural world. Covered in mud, my face streaked with sweat and tears, I whispered to Earth my promise. I will love you and cherish you, I will learn how to live and share what you teach me. This was the moment I discovered my life purpose, setting me on the path to who I am today.

I was twenty-four years old, more than half my lifetime ago, and Im still learning and still teaching. After that morning outside the sweat lodge, I dedicated myself to soaking up as much knowledge as possible about ancestral living skills. Soon I was teaching at various gatherings around the US and landed myself a summer guiding job at an outdoor survival school in the canyonlands of Utah. I realized that the hard-core survival approach was not what I wanted to do. Instead I was interested in helping people discover how to thrive in the wilderness, not just survive it and then head back to civilization for a hot shower and a cheeseburger. At the time, I didnt know if this was possible. I wondered if we modern people would even be able to stay alive on an all-wild food diet. I wasnt sure if we had lost the ability to live as hunter-gatherers but I knew one thing: I was willing to die if I found out that my body and mind were no longer functional under such circumstances.

A decade ago, I founded Living Wild, a small school in north-central Washington State. I was intrigued by the idea of learning to live as a hunter-gatherer, bringing people into a closer connection with nature in a way that couldnt be done in just a day or two. As a modern human, born into a culture of resource exploitation, I wanted to see if it was still possible to live sustained by nature in its purest form. My goal was to offer high-quality instruction in Stone Age living skills to give people the tools and confidence to live in the wilderness simply yet comfortably.

We have found over the years that the Stone Age skills that we teach are just a little piece of the puzzle that represents what I believe is our true humanity. A renewed focus on community building, gratitude and grief tending, and connecting with our ancestors all play a part in addition to the hands-on skills required to live in closer harmony with the land. I believe that on some fundamental level, we recognize that weve lost an essential intimacy with the natural world and with Earth and she is calling us back. There is a hunger to reconnect withto return tothis profound part of ourselves.