This book is for the entertainment and edification of its readers. While reasonable care has been exercised with respect to its accuracy, the publisher and the author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions in its content. Nor do we assume liability for any damages resulting from use of the information presented here.

Disparities in materials and design methods and the application of components may cause your results to vary from those shown here. The publisher and the author disclaim any liability for injury that may result from the use, proper or improper, of the information contained in this book. We do not guarantee that the information contained herein is complete, safe, or acurate, nor should it be considered a substitute for your good judgment and common sense.

Nothing in this book should be construed or interpreted to infringe on the rights of other persons or to violate criminal statutes. We urge you to obey all laws and respect all rights, including property rights, of others.

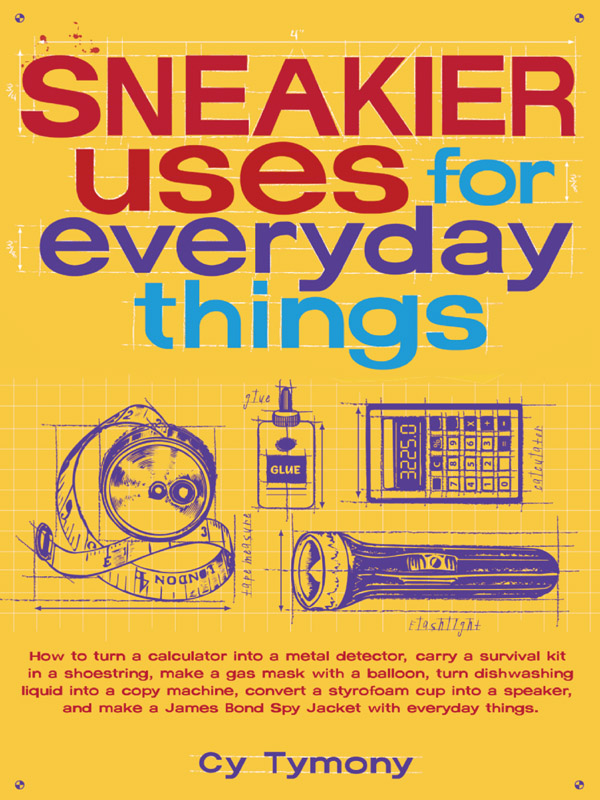

Contents

Part I

Sneaky Science Tricks

Part II

Sneaky Gadgets

Part III

Sneaky Survival Techniques

Part IV

Gadget Jacket

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to my agent, Sheree Bykofsky, for believing in the book from the start. Im also grateful for the assistance provided by Janet Rosen and Megan Buckley at her agency.

I want to thank Katie Anderson, my editor at Andrews McMeel, for her invaluable insights.

Im grateful to the following people who helped me get the word out about the first sneaky uses book:

Gayle Anderson, Sandy Cohen, Ken Hamblin, Deborah Rowe, Ira Flatow, Steve Cochran, Christopher G. Selfridge, Timothy M. Blangger, Cherie Courtade, Charles Bergquist, Mark Frauenfelder, Phillip M. Torrone, M. K. Donaldson, Paul MacGregor, David Chang, Jessica Warren, Steve Metsch, Jenifer N. Johnson, Jerry Davich, Jerry Reno, Austin Michael, Tony Lossano, Katey Schwartz, John Schatzel, Diane Lewis, Bob Kostanczuk, Marty Griffin, Mackenzie Miller, and Rebecca Schuler.

Im thankful for project evaluation and testing assistance provided by Bill Melzer, Sybil Smith, Isaac English, Jerry Anderson, and Raymond Moore.

And my love goes to my mother, Cloise Shaw, for giving me positive inspiration, a foundation in science, and a love of reading.

Introduction

E ver since the first tool was created, people and societies have been making sneaky uses of everyday things. Whether the adaptation is for novelty purposes or stems from a need for escape and survival, sneaky resourcefulness has produced numerous ingenious innovators. World War II, in particular, inspired many fine examples.

British Royal Air Force pilots were equipped by the Military Intelligence division (MI-9) with various concealed items, such as:

Shoelaces with magnets in the tips and a wire saw sewn in the fabric

Compasses and silk maps hidden in buttons and chess pieces

Boot heels with rubber stamps for document forgery

Cribbage game boards with crystal radios inside them

Escape pens that hid a compass, map, currency, and dye to tint clothing

Charles Fraser-Smiththe model for Ian Flemings character Q (for Quartermaster)supplied equipment and gadgets for secret agents and prisoners-of-war. Some of his special designs and gadgets included:

Flashlights with one real battery and a fake with a secret compartment

Cigarette lighters holding tiny cameras

Pens containing a paper-thin map, a compass, and a magnetic clip to balance it on a pin

Buttons containing a tiny compass

Badges and boot laces containing a Giglis wire saw (a flexible wire with saw teeth used by surgeons)

Fraser-Smith also developed a used match containing a magnetic needle that could be dropped in water to form a compass, maps printed on handkerchiefs in invisible ink, chess pieces and tobacco pipes with hidden compartments, edible rice-paper notepaper, a cigarette-holder telescope, and fur-lined pilot boots that could be converted into ordinary shoes (to avoid detection) using a knife hidden in the leather, the removed sheepskin legging sections then being converted into a vest).

In Germanys sixteenth-century Colditz Castle, prisoners of war constructed a two-man 19-foot glider with a 33-foot wingspan using cloth from sleeping bags, nails and wood from floorboards, and other materials from their cells.

The inspiration to do this came on a snowy day in December 1943 when prisoner Bill Goldfinch looked out his window over the town and noticed that the snowflakes outside were drifting upward. He thought it might be possible to escape from the old castle in a glider, using the updraft to get airborne.

With the help of a book from the prison library, Goldfinch drew up his specifications. The glider wings would have to have enough lift to carry the gliders pilot and one passenger over the town of Colditz, more than 300 feet below, and across the Mulde River.

In one of the castles attics, near an adjacent chapels roof they would use for a runway, the resourceful prisoners created a workshop. With shutters and mud made from attic dust, they constructed a false wall at one end of the attic and went to work, using drills made from nails, saw handles from bed boards, and saw blades from a wind-up record players spring and the frame around their iron window bars. To cover the gliders wooden frame they used bedsheets, which they painted with hot millet (part of their rations) to stiffen the fabric.

Takeoff was finally scheduled for the spring of 1945. The prisoners planned to assemble the glider and catapult it off the chapels roof, using a metal bathtub filled with concrete as ballast. The tub, secured to the glider with bedsheet ropes, would fall five stories. The glider would then sail out silently over the town of Colditz, giving its occupants a good head start over the German guards, who would soon discover a bathtub in the yard and two prisoners missing. However, the flight never took place, because the prisoners were rescued by the Americans in 1945. For pictures and more details about the Colditz glider, go to www.sneakyuses.com.